The Red Record

The excerpt below is reprinted with permission from Live Yankees by William H. Bunting, Tilbury House Publishing, South Thomaston, Maine and the Maine Maritime Museum,

Bath, Maine. 496 pages, 2009

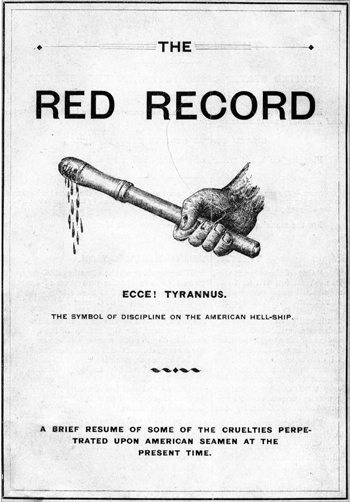

The publication in December 1895 of a thin booklet entitled The Red Record, subtitled Ecce! Tyrannus, containing a collection of sixty-four cases of alleged brutality inflicted upon seamen in American ships in the previous seven years, as recorded in the Coast Seaman’s Journal, published by the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific, did not help Arthur Sewall’s candidacy. The introduction read in part:

This pamphlet presents a concise and vivid view of one phase of the American seaman’s life. Considerations, not only of humanity, but of business expediency, as evidenced by the growing scarcity of seamen, demand public attention to the cause and cure of brutality to seamen…These cases of cruelty are so atrocious and so repellant to the sense of common decency, not to say justice, as to be almost incredible …Indeed, the incidents here mentioned are of the commonest order, the exceptional features of buckoism being of such a character as to be unprintable…The cause of cruelty to seamen lies in the mistaken idea of economy which obtains among ship-owners…The system originated and is maintained upon the theory that brutal ships’ officers can by threats and violence compel a small crew to do the work of the larger number of men required under a just system.

Fourteen of the cited cases involved Sewall ships. Solitaire, Rappahannock, Susquehanna, Roanoke, and the Benj. F. Packard each were cited twice. By comparison, the combined fleet of two dozen Cape Horners of the old partners Benjamin Flint and I. F. Chapman, twice as large as the Sewall fleet, accounted for five charges, two being earned by the M. P. Grace. The ten Cape Horners managed by Captain William Besse, of New Bedford, figured in a single incident. An excerpt from Roanoke’s second listing may be of interest, given the Sewalls’ surprise when it was revealed that Captain Hamilton had fallen off the wagon:

Captain Hamilton arrived at New York March 13, 1895. Crew charged that while the vessel was lying in Shanghai Edwin Davis, able seaman, fell from aloft, through fright at the threats of Second Mate Taylor, and was killed. The second mate is reported to have laughed at this…The day following this fatality Arthur Baker, able seaman, was working under the hatches. A bale of cotton was in danger of falling on him, and when the attention of First Mate “Black” Taylor was called to this he swore at the crew and ordered them to “go ahead.”…The bale fell on Baker, injuring him seriously…The first mate accused Frank McQueeney of being asleep on the lookout, and pounded him into insensibility with a belaying-pin. Captain Hamilton struck Carpenter Hansen on the head with a bottle, inflicting deep wounds, and afterward put him in irons and triced him up to the spanker-boom, where he was kept till nearly dead. Crew accused Captain Hamilton of drunkenness and neglect of his officers’ conduct.

Politically,

The Red Record

was well timed.

Fourteen deaths cited in The Red Record were “recorded under circumstances which justify the charge of murder.” However, only three of the sixty-four cases—none involved a Sewall ship—resulted in convictions, all for “brutality.” This was explained in part by the “disappearance” of officers upon a ship’s arrival in port. Forty cases were reported in San Francisco alone, and but one from a foreign port. “As cases of abuse are most frequent on vessels bound to foreign ports …the Record falls far short of the actual number of happenings.”

The claim by Red Record publisher, J. Elderkin, general secretary of the National Seamen’s Union of America, that “the strictest personal investigation into both sides of [each] case” was made is belied by confusion between Ned and Joe Sewall. It would appear that most accounts were taken on faith from newspaper stories, never a wise course. However, the overriding contention that American ships were often the scenes of intolerable brutality and abuse cannot be denied, along with the fact that ships of the Sewall fleet were disproportionately represented. The July 14, 1896, New York Times crowed:

The candidacy of Arthur Sewall of Bath, Me…on a platform which makes humanity its pretense, would cause amusement among many shipping people and seamen did it not incite to a feeling of indignation at the hypocrisy of the thing …Commendable as the Sewall fleet is, however, from the standpoint of commerce and art…it has been a tradition among sailormen that these noble vessels are floating hells, that on them men are starved and abused to a more outrageous extent than on any other American ships, and that is the same as saying on any other ships that sail the high seas.

On July 16, 1896, a letter from an Arthur S. Brunswick, Esq., 31 Park Row, New York City, was answered by 411 Front Street thusly:

Your letter addressed to our senior under date of July 15 has been handed to our firm, for reply to the inquiries you made therein. We will not undertake to answer them separately, but will merely say that we have had during the forty years we have employed labor in our Ship Yard, no trouble of any consequence. In regard to the allegations of the Red Book, as you term it, they are entirely without foundation so far as our knowledge and authority extend.

Arthur Sewall & Co.

The December 14, 1896, Bath Enterprise dealt with the locally sensitive subject of The Red Record by reprinting an article published in the (Republican) Kennebec Journal:

This publication is not an entertaining one for a Maine man to read. Out of the 64 cases mentioned, at least 36 were those in which Maine vessels and officers were implicated, in several instances more than once …Reputable men acquainted with seafaring have been found who admitted that they did not doubt that in the main most of these charges are true.

Politically, The Red Record was well timed. Tbe Maguire Act of 1895 protected coasting seamen—but only coasting seamen—from imprisonment for desertion. This led to a Supreme Court decision in the case of the barkentine Arago that held that seamen were exempted from the Thirteenth Amendment, which prohibited involuntary servitude. This, in turn, led to the passage of the White Act in December 1898, which not only limited the penalty for all American seamen for desertion in American ports to the forfeiture of wages and effects left behind, but prohibited all forms of corporal punishment. The LaFollate Seaman’s Act of 1915 resolved most remaining grievances of sailors’ labor leaders.