Lobster Industry Wrestles withWhale Issues

Continued from April 2020 Homepage

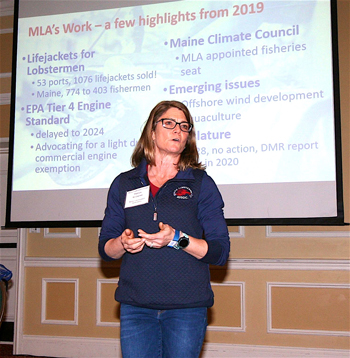

Patrice McCarron, Executive Director, Maine Lobstermen’s Association. “We believe management needs to be based on sound science and use the best available data. Maine will do its part, but the lobster fishery alone can’t solve this problem. Ten whales died in Canada last year. We couldn’t have solved that.” Laurie Schreiber photo.

The association studied data on injuries and deaths and found that other types of fishing gear, other regions and ship strikes are part of the problem, McCarron said. In cases where the cause of death was unknown, the federal government “wants to call all of the unknown ‘lobster,’ because we’re the biggest fishery,” she said. “We reject that.”

She added, “We know our gear interacts with whales and does cause harm.” But most whale deaths in the Gulf of Maine occurred before the existing suite of protective regulations was implemented, she said.

In a membership survey, “A lot of people said, ‘I think I can survive this round, but what comes next? I can’t even think about it,’” she said. “And I think that’s the fear we live with every day.”

The survey revealed there’s not a lot of support for removing rope from the water by trawling up, trap reductions, or fishing closures, she said.

The case was filed by

the

Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife, Conservation Law Foundation,

and the Humane Society.

The association is an intervener in a court case filed by four environmental groups in federal district court in Washington, D. C., which argues that the federal government has violated the Endangered Species Act and Marine Mammal Protection Act by allowing lobster fishing to continue. Monitoring the case is Mary Anne Mason, a retired partner of Washington, D.C. firm Crowell & Moring LLP, who is providing pro bono service to the association.

The case was filed by the Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife, Conservation Law Foundation, and the Humane Society, said Mason.

The case went to Judge James Boasberg, who birfurcated the case into two phases, she said.

The first phase addresses whether there was a legal issue that needed to be decided. Phase 1 has been ongoing since early 2018. The MLA became an intervener in the event that, if there were a ruling that there had been a violation of the law, the MLA would be in a position to represent the lobster fishery’s interest in a potential remedy, she explained.

In October 2019, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) went before the judge and requested that he stay the case until the Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Team finishes its work and a new biological opinion was issued.

“Not surprisingly, from the perspective of those who have watch this judge, the judge rather precipitously and forcefully rejected NMFS’ request,” Mason said. “He said, in rather emotional terms in his decision, that any delay was too much delay for the whales, that they are at a very precipitous part in their life cycle and that, if need be, he would be in a position to make a decision to cease activities that were harming this species until such time as NMFS took effective action.”

In November, the case went forward, and NMFS filed a motion for summary judgment, in which it argued that there’s no evidence that there have been any entanglements or serious injury and mortality to the species associated with federal lobstering since the whale plan went into effect in 2010, Mason said.

“What the environmental groups are saying is that the biological opinion was unlawful because it failed to take into account the sublethal effects of entanglements, that it only looked at serious injuries and mortality,” Mason continued.

She added, “We expect the judge to issue a decision at an time.”

In January, she said, NMFS filed an additional submission with the court indicating that the biological opinion will be delayed until July or later.

“I can’t say what the judge is going to do, but the judge has signaled a great deal of concern for the species,” she said.

Assuming the judge decides there is a violation of the law, he will move forward to a remedy phase, she said. At that point, the MLA, as an intervener, will be active on behalf of the industry, she said.

“The science is very clear that, within Maine state waters and within 10 to 15 miles of state boundary lines, right whales are not an issue,” said one fisherman. “They’re just not there.”

He added, “Maybe we’re barking up the wrong tree. Rope and ships are not the biggest threat to right whales. The biggest threat to whales in general is CO2. If we don’t get a handle on CO2, we can do all the protection we want—it won’t make a difference.”

“I can’t say what the

judge is going to do,

but the judge has

signaled a great deal of

concern for the species.”

– Attorney Mary Anne Mason

McCarron noted that climate change and warming waters appear to be causing a shift in right whale distribution, which complicates the issue.

“But the laws don’t regulate the environment. They regulate human interaction,” she said. “It doesn’t get us off the hook in terms of our potential to harm right whales.”

McCarron added, “There’s a strong potential that a judge will be deciding how you fish, period.”

Other issues on the front burner, McCarron said, include climate change impacts on the fisheries and offshore wind development.

“We want to make sure, as we make our fishery greener and help contribute to solving climate change, that we’ll still be able to fish and make a living,” she said.

She encouraged fishermen to remain abreast of offshore leases so they could be prepared to comment on traditional uses of proposed lease areas if they happen in their area.

The bait crisis was another big topic over the past year, she said.

“The news on herring is not good,” she said, noting severe quota cuts since 2018. Still, she noted, fishermen were able to find alternatives.

“It’s been a lot of menhaden,” she said. “But it’s still not filling the gap….How we’re diversifying our bait supply is still largely unknown. So be cautious going into this season.”

Lobster landings strong

At $673,910,558, the value of Maine’s commercially harvested marine resources in 2019 was the second highest of all time, and an increase of more than $26 million over 2018, according to a Department of Marine Resources (DMR) press release.

Maine’s lobster harvesters landed 100,725,013 pounds, marking the ninth year in a row, and only the ninth ever, of landings that topped 100 million pounds. Despite a 17 percent decline in pounds landed from 2018, the value topped $485 million, ranking 2019 as the fourth most lucrative for the iconic fishery on the strength of a 20 percent increase in per-pound value.

Even with a slow start last year, Maine’s lobster industry ended the year strong, with landings picking up significantly in the last few months, DMR Commissioner Patrick Keliher said in the release. There are many factors in the marine environment that impact landings. Last year the cold spring caused a delay in the molt which is when lobsters shed their shells and the bulk of the harvest occurs. Fishermen held off until the shed happened, so fishing was slow early but picked up later in the year, said Keliher.

According to data published by NOAA, American lobster was the most valuable single species harvested in the U.S. in 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018, with Maine landings accounting for approximately 80 percent of that value each year.

Elvers again topped $2,000 per pound which resulted in an overall value of $20,119,194, ranking it as the second most valuable species harvested in Maine in 2019 and once again by far the most valuable on a per pound basis.

Softshell clammers raked in an additional 623,000 pounds compared to 2018, which generated more than $18 million for harvesters and made softshell clams Maine’s third most valuable species. The uptick in value was due to the additional landings plus a 30 percent increase in value, which jumped from $1.80 per pound in 2018 to $2.34 per pound in 2019.

3.2 million pounds of oysters were harvested in 2019, an increase of 460,911 pounds over 2018, resulting in a jump in value of $336,334, for a total value of $7,622,441, making oysters the fourth most valuable species.

The fifth and sixth most valuable fisheries in Maine were blood worms, used as bait for species including striped bass, valued at $6,283,315, and urchins, worth $5,835,917.