Maine Fishermen Fish Alaska Salmon & Maine Lobster

by Sarah Craighead Dedmon

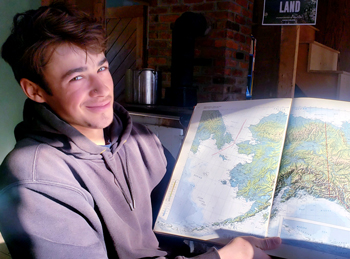

Asher Molyneaux, age 17, holds a map of Alaska at home in East Machias. Last summer Molyneaux traveled to Bristol Bay for five weeks of salmon fishing with fellow Mainer Chris Mullen, then returned Downeast as quickly as possible to begin the blueberry harvest. Photo by Sarah Craighead Dedmon.

Within weeks of his high school graduation, Asher Molyneaux traveled 3,600 miles from East Machias to Dillingham, Alaska, where he joined Captain Chris Mullen and his brother aboard the F/V Chris R. For the next month, the three Mainers worked and slept on Bristol Bay, according to a schedule set by millions of sockeye salmon.

“There is no ‘at night’, because we go to work for 10 hours every 12 hours,” said Captain Mullen of Machias, who found his passion for Alaskan salmon fishing after working there as a fisheries observer in 1988. Instead of a workday divided into day and night, Alaskan salmon fishermen live by “openers,” those parts of the day when managers open an area to fishing. It’s unlike anything fishermen encounter in Maine.

“The openers define the day, and spin around the clock. It does take your whole concept of time and twist it up and crumple it and throw it overboard,” said Molyneaux, age 17. “That’s the beauty of it — it’s this bonanza energy. You have that one month, so you go as hard as you can. ”

Bristol Bay is one of the most fertile salmon fishing grounds in North America, but is currently living under the shadow of Pebble Mine, a massive proposed copper mine blocked by the Environmental Protection Agency under President Obama, but recently greenlighted by the Trump administration. Opponents fear mine runoff into the Bristol Bay watershed will poison the salmon.

During the short season, 1,500 boats descend on Bristol Bay, and position themselves near one of its six major rivers. For the F/V Chris R., that’s the Nushagak River, affectionately known as “The Nush.” As salmon make their way in on the flood tide, fishery managers count the fish entering the rivers to spawn. Once that “escapement” reaches a certain threshold, fishermen are given the green light to put in their nets. That could be at 2 p.m., or 2 a.m., so the boats need to be ready.

“The [fishery managers] do drop hints, and there are announcements about what escapements they’ve seen so far. When it gets really close, they give you a standby for a possible opening,” said Mullen.

Sockeye salmon are caught using a 900-foot drift gillnet, and most of the boats’ needs — from new nets to groceries to fuel — are handled by large tenders spread out across the bay. When a ship’s hold is full, it’s unloaded by crane onto the tender, too. The load varies, but for the F/V Chris R. it can go as high as 6,500 pounds.

“You can catch a lot of fish in 12 hours in Bristol Bay,” said Mullen, who partners with Leader Creek, a seafood company which operates the tenders and allows fishermen to purchase salmon back at wholesale prices.

Every year, Mullen brings thousands of pounds of the wild-caught salmon back to Maine and sells it through his website, Mongr.net, also delivering to several locations throughout Maine.

Management

The F/V Chris R. at anchor in Bristol Bay, where the crew readies to clean up and nap after an “opener.” Per state law, all Alaskan salmon boats must measure no longer than 32 feet. “They’re wider and heavier, more like tugboat or a dragger,” said Captain Mullen. “They have to be heavy because you have to be able to carry a huge amount of weight.” Every 12 hours a tender offloads thousands of pounds of salmon, enabling the crew to stay at sea for the full season. Photo courtesy Chris Mullen.

In 2019, Alaska news outlets celebrated a banner year for sockeye, noting that fishermen caught Bristol Bay’s two billionth sockeye salmon since records were first kept. Forrest Bowers of the Alaska Department of Fish & Game said the fishery’s recent success is partly attributed to its management, and partly to the environment. Right now, the environment seems to be working in the sockeye’s favor.

“North of the Alaska peninsula, where Bristol Bay lies, the warming waters have had a positive effect on salmon,” said Bowers. “In the northwest arctic we’re seeing salmon expand into areas where they haven’t really been before.”

Bowers notes the fishery wasn’t always thriving. Before statehood, it was managed by the federal government and salmon numbers declined until President Eisenhower declared the fishery a federal disaster in 1953. Salmon hit an all-time low in 1959, the same year that Alaska became a state. That is not entirely a coincidence, said Bowers.

“A big part of the reason for Alaska becoming a state was to gain control of our natural resources,” said Bowers. “Our constitution has extensive language about how natural resources are to be managed, and rebuilding our salmon runs was a high priority for Alaska as a state.”

Though the constitution initially set out “No Exclusive Right of Fishery,” a clause designed to preserve equal access, a 1972 amendment allows the state to utilize Limited Entry principals. It’s through that program that Mullen attained his Alaskan salmon license. He purchased it from a friend who was retiring

“The [license prices] are high, but they go up and down. They’re bought and sold on the open market, almost like real estate,” said Mullen. Alaska prevents corporate consolidation of the fishery with an owner-operator clause, requiring the permit holder to be on the boat.

“Even though there’s a high price tag associated with it, it does permit more open access to the licenses,” said Mullen.

When the salmon season ended, Molyneaux made his way back to the blueberry barrens of Washington County, just in time for the harvest. Then, he set out on a lobster boat, too. Like Mullen, Molyneaux plans to return to Alaska this year, but possibly for longer than five weeks. After sockeye season, Molyneaux said he could go seining for pink salmon in southeast Alaska, crabbing, or halibut fishing, just so long as it’s some kind of fishing.

“I’ve worked a lot of jobs on land and I’ve gotten up in the morning and I’ve just kind of felt like — is there anything I could do to not go to work?” he said. “I’ve never felt that way fishing. I might be tired, and sometimes it’s awful shoveling frozen fish skeletons around, but no matter what, it’s amazing.”