River Herring Come Back Not Just a Flash in the Pan

Theodore Willis, PhD, University of Southern Maine

DMR mounted a

quiet crusade to

reintroduce alewives

through stocking and

fixing passage at dams.

“So many they turned the water black”, “hundreds of barrels in a single tide”. These are quotes describing river herring migrations 75 – 100 years ago. River herring are alewife and blueback herring, small bait fish related to Atlantic herring. They are anadromous (an-ad-dro-mus), meaning they swim into freshwater to spawn and both adults and juveniles later return to the sea. They frequented nearly every stream and river of the Atlantic coast. The history of the fishery in Maine goes back to the early 1600s, when alewives from Arrowsic were reported as good bait for cod. The big river basins: Penobscot, Kennebec and St. Croix, along with dozens of smaller rivers and streams, hosted millions of adults each year and kicked billions of juveniles out into the marine environment. The juveniles fed hungry populations of groundfish, tuna, whales, seals and sea birds that graced Maine’s bays and coves.

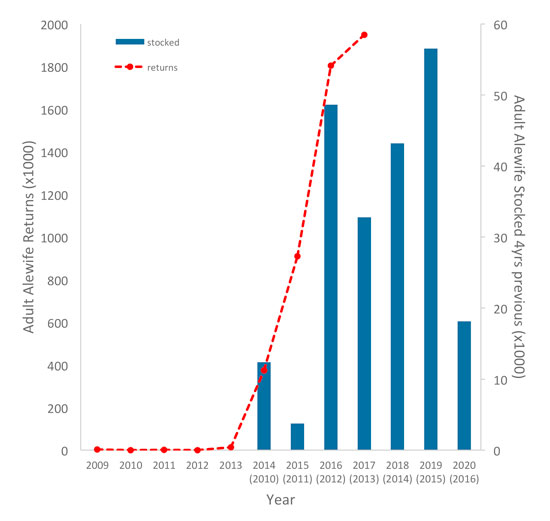

Adult river herring returns (line) and stocking (bar) data for the Penobscot River, consisting mostly of alewife. Before 2014 counts were collected at Milford Dam. After 2014 counts were collected from Orono Dam and Blackman Stream. Stocking data are lagged forward by four years (parentheses below year), the average alewife time at seas, to show association between stocking and adult returns. Data from Maine Dept. of Marine Resources

By the late 1970s river herring were largely forgotten by most Mainers living inland and on the coast. Where dams hadn’t blocked their way completely, pollution made the rivers un-passable. The Clean Water Act of 1977 made it possible to clean up the rivers so they supported aquatic life. Maine’s Dept. of Marine Resources kept a candle burning for the little fish, taking steps whenever possible to bring river herring back. With the help of places like Damariscotta, Warren and Orland, where the fish never completely disappeared, DMR mounted a quiet crusade to reintroduce alewives through stocking and fixing passage at dams. The Kennebec Hydro-Developers Agreement, built around the decommissioning and removal of Edwards Dam in 1999, kicked off 30 years of concerted restoration efforts between Waterville and Popham Beach. We are seeing the fruits of those efforts today at Benton Falls, where 3.8 million alewives passed in 2017. The most recent strides are being made in the Penobscot as part of the Penobscot River Restoration Project. The list of partners behind the PRRP is as long as the number of rivers flowing into Penobscot Bay.

What does this all mean for the lobster fishery? One word, BAIT! Alewives are a home-grown spring lobster bait. The mix of plump, oily bodies laden with spawn is a potent attractor for lobster and crab. The challenge is that they are only available for about ten weeks. The Alewife Harvesters of Maine, an industry and advocacy group for Maine’s river fishermen, are looking for ways to extend the supply into the summer season and maintain sustainable fisheries for the future. But that’s not the only use for these fish.

The high returns

are ultimately

related to

favorable at

sea conditions.

Alewives are also harbingers of healthy ecosystems and are ambassadors for ocean life. In freshwater, alewives encounter people and communities directly. Many communities are starting alewife counts at fish ladders, data that is then provided to towns and DMR to assess run health. DMR has its own sentinel locations where sophisticated electronics keep track of how many alewives are returning year after year.

DMR uses restoration stocking of adults (brood stocking) to kick start populations that have disappeared. The resulting juveniles return to the ponds where they were spawned between three and five years later. Four years ago, the Penobscot River had 12,708 alewife returning to the river above Veazie and 49,000 alewife were stocked by DMR in the lakes. In 2017 about 1.95 million returned to the Penobscot. Growth in these new restoration projects is nearly exponential, as much as doubling for every year of stocking. Older projects also did well in 2017: Benton Falls set a record. Over 40,000 alewives passed up the Saco, the third largest count in two decades. Even the embattled St. Croix exceeded 158,000 fish for the first time in 20 years.

Alewife fisheries also had a good year. Locations like Warren and Benton Falls did extremely well, but weather affected some smaller harvest operations. The cool spring pushed fish out of some of the smaller streams, like Nequasset and Dresden Mills. Many locations requested an extension on their season to combat the slow early fishing. The high returns are ultimately related to favorable at sea conditions. Some combination of ample food, low predation and low bycatch in the last three to five years brought more alewives to spawning age.

Even though counts and harvests were up in 2017, there are still challenges on the horizon. DMR is concerned about the coastwide river herring population. As well as Maine is doing, southern New England runs are declining. Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission is planning a blueback herring assessment, separating the two species of river herring to focus on just bluebacks, a species we know little about in Maine. Overall, river herring numbers have been about the same across New England for a decade, but for Maine’s river herring fishermen and fans things appear to be looking up.