Consider the Lobster Molt

Diane Cowan, Phd

After escaping from the old exoskeleton, the freshly-molted lobster buries its old shell. In the case of this photo, the lobster lived under a rock (top of photo) not roomy enough for shedding, so he shed out in the open, attempted to bury his old shell, and then scurried back under his rock to hide. He would return to begin eating the old shell. Photo by Diane Cowan, Lobster Conservancy Cove (former lobster pound) in Friendship, Maine.

From the time egg meets sperm until the hour of death, lobster life consists of preparing for (premolt), undergoing (ecdysis or shedding), and recovering from (postmolt) ecdysis via the process of molting.

Preparing to shed consists of major renovations to the structure the lobster lives in – the dead shell – and includes upkeep and renewal of live limbs, sensory hairs, and even muscle tissue.

Pre-molt renovations include:

1. building a new larger soft scrunched up shell that fits beneath the old one

2. regenerating missing parts, such as claws, antennae, and legs

3. recycling calcium by dissolving edges of carapace and joints

4. storing calcium in hemolymph (basically, lobster blood) and on either side of the stomach as gastroliths (literally, stomach stones)

5. atrophy muscles in major chelipeds (claws!) so they can squeeze out of the narrow joints (knuckles)

All lobsters are subject

to Pre Molt Syndrome

behavioral signs.

Premolt lobsters need special care because while they look and feel hard-shelled on the surface, they are weak around the edges, the muscles in their claws have atrophied, and the delicate limb buds break off easily.

Behavioral signs that a lobster is getting ready to shed include increased activity such as spending more time out in the open during daylight hours, building and barricading entrances to hiding places, and the general fidgeting I think of as pre-molt syndrome (PMS). All lobsters are subject to PMS. Male, female, and the less than one year olds who have yet to be marked by gender.

If possible:

• Keep these lobsters separate from hard shells and new shells;

• Try to give them space to move around (and possibly shed); and

• Make sure they have plenty of cool, well-oxygenated water.

Next step

Shedding lobster. Parts of claws and abdomen are of the old shell, but, look at the middle parts: there are two carapaces, old paler colored on the lower right center, lifted up to expose the new dark shell underneath. Above that, the pale gray yellowish stuff are the gills. The lobster is shedding the lining of its gills. While doing so, the lobster cannot breathe so it’d better hurry up and finish shedding. The front of the lobster face is also showing at the very bottom of the photo just behind the old carapace where you can plainly see that this lobster is shedding the exoskeleton covering its eyes and puking up the lining of its stomach. New eyes are black. The old look white, but it is shell cover over the eyes. Amazing to watch if you ever get the chance! New eyes are black.

Ecdysis – the act of shedding – looks seriously agonizing, but the lobster gets an entire new skeleton, replacement parts, and sensory structures including hairs for smell and taste, and new shell coverings for the eyes. First rate brand new parts with no prosthetics, joint replacement, or cataract surgery. Hmmm... Sounds amazing.

Duration of the laborious part of shedding varies with body size. The rate limiting step is getting the claws out. Even with joints softened and muscles atrophied, it takes a one pound lobster about a half hour to shed – once it has rolled over on its side – add at least another 30 minutes for a 10 pounder.

When the lobster is ready to shed, she swallows water that provides the pressure needed to push away the old shell. After a few minutes of gulping water, the carapace lifts exposing new dark shell along the sides and revealing a fluid-filled membrane at the back junction where body meets tail. During the first thirty minutes of shedding the fluid fills the lining between new and old shell pushing the carapace higher and higher until the membrane breaks.

At this point, the lobster falls over on its side, if it can. Please, if you catch a lobster in the act, give the lobster sufficient space and some substrate to cling to; a plastic bucket is not a good place to shed – a bit slippery with little room to lie down.

The first parts to harden

are the mandibles she uses

to eat the softest parts of

the old shell.

Next, it sheds the lining of the gills and spits up its stomach to shed the lining of the gut – by this time the back edge of the old carapace looks like it’s pinching the new shell of her rostrum. If she’s female, the lining of her seminal receptacle where she stores sperm is also shed. All the while she keeps pulling and pulling and straining to extract the claws from the old shell. Finally, when the shriveled up claws escape, the lobster flicks her abdomen to cast off that old armor and she’s free.

The new-shell, rag-soft lobster with cooked-spaghetti looking antennae lies helpless on the bottom swallowing water to swell up to her new size. The body fills up relatively quickly, within about half hour, she’s almost full grown and can prop herself up on wobbly legs like a newborn cold. It takes hours for the claws to reach their full size.

The first parts to harden are the mandibles she uses to eat the softest parts of the old shell (that part where the membrane broke so she could get out). Then she buries and saves the rest to munch on later.

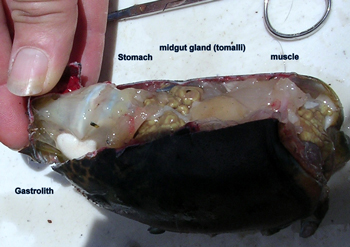

A window of exoskeleton at the dorsal (back) surface of the lobster removed to show what lies underneath the top of a lobster that is just about to shed. Claws, other limbs, and abdomen have been removed. The anteriormost structure is the stomach shown exposed at the front of the “head” region. Some call this the mermaid’s purse. Gastrolith (white) on left side of stomach (there’s another on right side not shown), midgut gland (tomalli), and muscle tissue also labeled. The gastrolith is a calcium reserve only available for the molt period.

The old shell still looks like an entire lobster. The only part that is broken open is the junction where body meets tail.

People often mistake an empty crustacean molt shell for a dead animal. To determine whether the crab or lobster shell you find on the beach belongs to a dead animal or live one, look at the eyes. If the eyes are black, it’s a carcass, but, if the eyes are clear, then you are looking at a molt shell and seeing the old dead shell that covered the living eyes.

Incidentally, but perhaps obviously, the reason the lobster has to go through all this molting is because the shell is made up of dead tissue that can’t grow with the lobster.

Handling tips for soft lobsters:

Lobsters are particularly vulnerable to injury and disease a few days before shedding through a couple of weeks after.

A typical lobster embryo

sheds 35 times inside the egg

and completes four molts in

its planktonic stage.

Soft-shelled lobsters are particularly prone to external bodily harm inflicted by trap and tank mates. Less conspicuous damage, such as gill abrasions and internal injuries, are also more common during the shed.

Hauling a trap aboard with 20 or 30 intact lobsters inside is a beautiful and awe-inspiring sight. But, while the lobsters usually don’t harm each other on the way up, once agitated, they start snapping at whatever they can grab, which is usually each other. A common consequence is loss of limbs.

Here are a few practices that can help minimize damage to trap-caught shedders.

• Remove and release undersized and egg-bearing female lobsters first so they no longer pose a threat to each other. Unharmed undersized lobsters will grow up more quickly and undisturbed eggers are less likely to drop eggs prematurely.

• If shorts are attached to each other, throw them overboard together. They’ll let go once they hit the water.

• Whenever possible, keep lobsters separate from each other until you are ready to band them. A shallow, compartmentalized tray or box is handy for this. And,

• Use soft bands on the claws of shedders.

How does temperature relate to the molt cycle?

On left, a freshly-molted very, very soft-shelled juvenile lobster. On right, the empty exuvia (cast molt shell) left behind by the same lobster at Lowell’s Cove in Harpswell.

Temperature has a great deal to do with when and how often a lobster molts. In the laboratory, scientists have speeded up the process to raise a one-pound lobster in two years by elevating temperature and providing adequate food. These fast-growing lab lobsters don’t taste nearly as good as their wild counterparts, which typically take about seven years to reach a weight of one pound. Molting is seasonal. The bulk of the spring molt for the adult population occurs with the rapid increase in water temperature as well as daylight hours. The corresponding fall molt coincides with a rapid decrease in water temperature and shortening of daylight hours. Inshore, winter molting is rare, but it does happen. It takes longer for the new shell to harden in cold water. The duration to hardening depends on water temperature, nutrition, water quality, and the size of the lobster.

How often do lobsters shed?

A typical lobster embryo sheds 35 times inside the egg and completes four molts in its planktonic stage. The number of molts before winter that first year depends on when the post larva settles to the bottom. The post larva molts into a fifth stage when it settles to the bottom. If settlement occurs in July, the lobster will keep growing until November and may molt up to about once a month or about four more times. That’s 35 times in the egg, four in the water column, one when it reaches the bottom, and four more times that season, totaling 44 molts before the lobster has reached one year of age! During the second year, juvenile lobsters molt about every other month from May through November, completing four molts in that year. After that, molts get further and further apart. A typical third- and fourth-year juvenile molts two or three times a year. Fifth- and sixth-year lobsters molt once or twice. By the seventh year, molting takes place no more than once a year. From then on, lobsters molt only once every two or three years. Ultimately, the frequency and time between molts depends on how long it takes the lobster to fill the empty space in its new, larger shell. So, the bigger the shell, the longer between molts.

I could say a lot more about molting, and if you are still reading this, maybe you would like to know more. Feel free to contact me.

Diane F. Cowan, Ph.D.,

Executive Director, The Lobster Conservancy

PO Box 235, Friendship, ME 04547

207-542-9789