Normal is the New Cold

by Andrew Pershing, Gulf of Maine Institute

Cold this year? Compared to what?

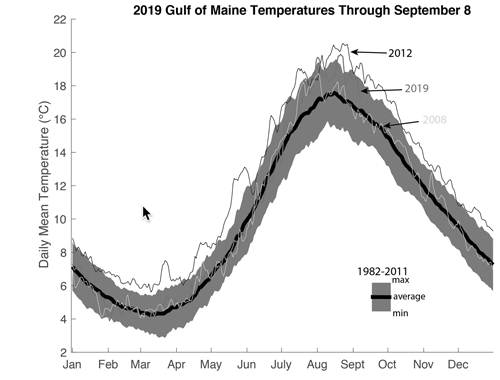

Words like “cold” and “warm” are relative measures. They imply some expected temperature — some notion of normal. Climatologists usually reference conditions against a 30-year average, and in our work on sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Maine, we use 1982-2011 (the heavy black line in the figure below with the blue shading indicating the min and max over that period).

Relative to this baseline, the Gulf of Maine in 2019 (red line) was decidedly average through mid July, and temperatures were very similar to those in 2008 (yellow line).

The 1982-2011 period is a great baseline for climate statistics, but it isn’t necessarily the way most of us experience the world. For example, I moved to Maine in 2006. A good baseline for me might be the period 2006-2018. My baseline includes 2012, 2016, and 2018 — years that featured intense marine heatwaves. So, relative to my personal baseline, 2019 has been a cold year.

The issue of baselines — what conditions are expected and what conditions are surprising — is a critical part of how we adapt to a changing climate.

You can read more about our work on baselines, trends, and surprises in our new paper, covered in detail by Maine Public Radio.

July was really hot.

July 2019 was the warmest July ever recorded in the Northeast and over much of the planet. The Gulf warmed up quickly through July, with the periods July 25–August 9 and August 18–25 qualifying as marine heatwaves.

While we technically reached heatwave status, heatwaves are also defined against our 1982-2011 baseline. The figure below plots each year as a horizontal ribbon, with pinks and reds indicating days that were above normal (blues indicate colder than normal).

You can see how the red really starts to dominate around 2010. You can also see how ubiquitous heatwaves (periods with temperatures well above the baseline, indicated by black dots) have been since 2012.

2019 in context

In many ways, very warm conditions in July and August in the Gulf of Maine are no longer a surprise. The strongest signal of warming in our region is in the summer and the fall. My colleague Andrew Thomas at University of Maine has described this as summer (or summer-like conditions) extending deeper into the year.

Winters are also warming, both on land and in the sea, but the warming is weaker. There are also some signs that our winters are getting more variable, with cold winters like this year and 2015 coexisting with warm winters like 2012 and 2016. Atmospheric scientists are actively debating whether the loss of sea ice in the Arctic could lead to more variable winters in our region.

We still have a few months left in 2019. Hurricane Dorian mixed things up in the eastern Gulf of Maine, and we’ve had some fall-like weather. This has brought the average temperature of the Gulf down to just slightly above normal. However, NOAA’s seasonal outlook suggests that there is a strong chance the rest of 2019 will be warmer than normal. If so, that would continue our pattern of ending the year with very warm conditions in the Gulf.