A Warming Gulf of Maine

Collaborative Science is Key to Protecting

Fishing Livelihoods

by Roger Stephenson

We’re really in the

crosshairs of climate

change right now.

– Andrew Pershing,

Gulf of Maine

Research Institute

Throughout the industrial revolution our oceans have played an important role that until recently has been all but invisible: the sucking in of 90 percent of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases. Since 1970, global sea surface temperature has increased by around 1 degree F. The ocean is warmer today than at any time since record-keeping began. In a 10-year period ending in 2013, the Gulf of Maine was the fastest warming body of ocean on the globe. People refer to the “2012 heat wave,” when average water temperatures reached their highest levels recorded throughout 6 generations of Maine fishermen. And when measured last December, water feeding into the Gulf through the Northeast Channel was 11 degrees warmer than normal. Absent the ocean’s role, our lives on land would be very different. But the fact is, life under the water’s surface is becoming much, much different.

Much has been written elsewhere about the warming gulf and its implications, in peer reviewed scientific journals, trade journals, and newspapers – enough that this column will simply serve as attempt to summarize what scientists have observed, briefly highlight winners and losers in warmer waters, and point out some of the implications for the Maine fishing community and for fisheries regulators.

Dr. Andrew Pershing is chief scientific officer at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute. Dr. Andrew Thomas is a research professor in oceanography at the University of Maine. I’ve had the pleasure of meeting both of these experts, each of whom has contributed significantly to the scientific and public understanding in what is being observed and what the data can mean to the Gulf of Maine ecosystem.

Dr. Pershing lifted the lid, so to speak. His research that showed the Gulf of Maine was the among the fastest warming areas of ocean on the globe. In speaking with the Portland Press in 2015, Pershing said, “we’re really in the crosshairs of climate change right now.”

Dr. Thomas, an oceanographer at the University of Maine, was the lead author of a scientific paper on sea surface temperature published in Elementa (a paper that included Dr. Pershing and 7 other researchers). The research results indicate the Gulf of Maine “summer” is two months longer than it was back in the early 1980s. In turn, fisheries biologists looked at the trend of longer periods of warmer water as one reason for the observed northward shifts of American lobster, Atlantic herring and Atlantic mackerel.

Scientists recognize, and fishermen have observed, winners and losers in the changing climate in the Gulf of Maine. Dr. Jonathan Hare leads the Climate Research Program at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center at NOAA. According to a June 2012 presentation on the effects of climate on fisheries resources of the New England region, Hare explains croakers are “winners” and Atlantic cod is a potential “loser” in climate change in the New England region. And biologists believe that warming waters are to blame for the Maine shrimp fishery collapse.

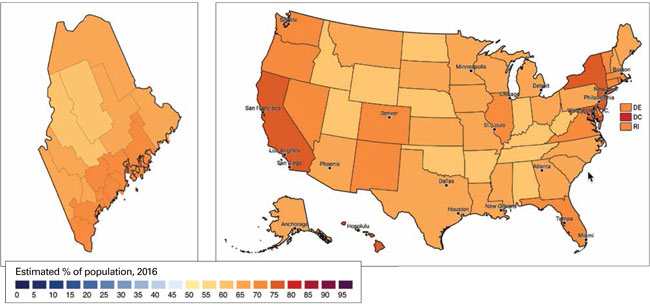

Estimated Percent of Adults Who Think Global Warming

is Happening, 2016

Maps courtesy of Yale Program on Climate Communication from their report “Yale Climate Opinion Maps – U.S. 2018.” The YPCC bears no responsibility for the analyses or interpretations of the data presented here.

Yet a warming Gulf is attracting southern species of fish whose populations, at least in the past, were centered in warmer waters in the mid-Atlantic; the mid-Atlantic population of Black sea bass is an example.

Longfin squid, whose population center is considered to be between Georges Bank and Cape Hatteras, appeared in the Gulf in such numbers that fishermen were quick to take advantage from Cape Cod to New Brunswick Canada. Other species, from even warmer waters, have presented themselves in nets and traps: triggerfish, tile fish, and the snowy grouper, a fish normally found in the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico.

And what about lobster? Research from the GMRI indicates that warming waters contributed to the collapse of lobster populations off of Rhode Island and Connecticut. In contrast, the same study says Maine lobster populations and juvenile survival have benefitted from some degree of warming in northern waters, coupled with decades-long conservation efforts initiated by fishermen. Despite conservation efforts the booming Maine populations may be temporary: recent research led by scientists Malin Pinsky and James Morley suggests that, if current warming trends continue, lobster could shift 200 miles north into Canadian waters.

Temperature has increased. In warmer waters oxygen levels decline and scientists expect low oxygen areas to get seasonally larger and in effect reduce or at the very least shift livable environments for different species of fish. In short, Gulf of Maine habitats are changing – from the clam flats outward.

Ninety seven percent of scientists agree fossil fuel emissions over the past century are contributing significantly to a changing climate. A majority of Maine citizens consider climate change real and impacting Maine, (69 percent) and caused chiefly by the burning of fossil fuels (53 percent).Maine native Dr. Malin Pinsky is an associate professor in Rutgers University’s Department of Ecology, Evolution and Natural Resources. His and Morley’s recent study examined the impacts on hundreds of Gulf of Maine species from warming, using several different climate change scenarios to predict different ocean temperatures. These models are based on in part how much greenhouse gases are pumped into our atmosphere in the coming decades. In an interview with the Portland Press Herald in May, Pinsky said, “Sticking to the Paris agreement [the international effort to combat climate change] would help our fisheries significantly.” Last year the Trump Administration withdrew the US from the Paris Agreement.

Lobster could shift

200 miles north into

Canadian waters.

What is, or will be, the new normal? To a cold blooded fish, even a couple of degrees temperature rise will impact how it grows and where it goes- two basic impacts that will define a new normal for men and women who make their livelihoods in Maine’s fishing industry.

The Gulf of Maine is not immune to climate change impacts. Hundreds of millions of dollars are at stake as the fishing industry, communities, scientists and agencies make decisions about the management of fisheries resources. Stakeholders are moving past single-species management to ecosystem based fisheries management so that decisions for species are made in a holistic manner – taking into account environmental changes, health of the habitat, interactions with other species, and other factors.

Perhaps the latest news on how this ecosystem approach unfolds in Maine is the Stonington-based Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries, which is helping lead a new pilot program called the Eastern Maine Coastal Current Collaborative, or EM3C. The collaborative includes the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries, NOAA Fisheries, and the Department of Marine Resources. The mission of EM3C is “to develop a research ‘framework’ for ecosystem-based fisheries management” in one region of the Gulf. Working in communities and with other groups in the state over the next five years, the Center intends to make sure local knowledge and experiences of fishermen play a real role in determining the direction and focus of fisheries and ocean research, and contribute to the benefit of the resource, our patch of ocean, and the people making their livelihoods on the water.

Roger Stephenson serves on the policy advisory committee for New Hampshire Sea Grant, and on the management committee for the Piscataqua Region Estuaries Partnership. He works for the Union of Concerned Scientists in New England.

See and use interactive Yale Climate Opinion Maps–U.S. 2018 here.