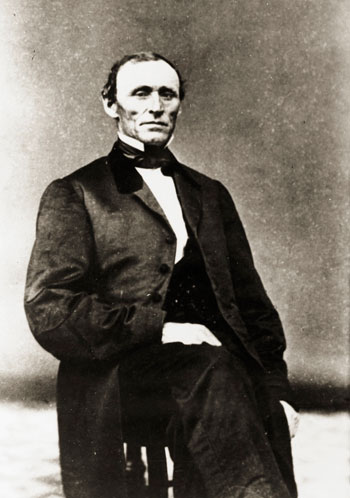

William McGilvery: Merchant,

Ship Owner, Mystery

by Tom Seymour

The 201' Henrietta. The largest ship ever built in South Carolina. It was built by Maine shipwrights for William McGilvery who shipped South Carolina yellow pine to northern shipbuilders. McGilvery was an early entrant in what became a lumber boom in the vast yellow pine forests of South Carolina. Damaged in a storm in the Philippines, she awaits being cut up for firewood. Image courtesy of Penobscot Marine Museum.

William McGilvery, born in Searsport, Maine, on February, 1814, was a successful and renowned businessman. His holdings were many and varied, from houses to ships. One of his early ventures was when Captain McGilvery carried a cargo of grain to Ireland during the great famine of 1847 in the bark Henrietta.

In 1859, Captain McGilvery became partners with Daniel S. Goodell and build sailing vessels at Mack’s Point in Searsport. Later McGilvery had a telegraph set up in Miss Lucy Edwards’ millinery and dry goods store in Searsport during the Civil War. Miss Edwards became proficient in the use of the telegraph, thus allowing Searsport to receive daily notices from the front. These bulletins were read every day at an appointed time, from the front door of the store.

Another, and perhaps his most notable business venture, was when William McGilvery and Sea Captain Jonathan C. Nickels, also of Searsport, then living in South Carolina, teamed up to build a great ship to work the lumber trade. This was the largest wooden sailing ship ever built in South Carolina and the last vessel McGilvery ever built.

The Henrietta was

the largest wooden

vessel ever built

in South Carolina.

The vessel, Henrietta, a square-rigged cargo ship, was built in order to carry longleaf pine and oak from South Carolina to waiting shipyards in Maine. Southern yellow pine was much in demand by Maine shipbuilders and businessmen such as McGilvery knew a good opportunity when they saw it. But the cost of shipping using available commercial means was prohibitive, so McGilvery and Captain Nickels decided to have their own cargo ship built order circumvent high shipping costs.

The 200-foot, 3-masted ship was built in Bucksville, South Carolina. Bucksville, as it turns out, was named for another Mainer, a shrewd businessman, Henry Buck of Bucksport, Maine. At its height, Bucksville was home to 700 residents, all of whom were connected in one way or the other with the lumber industry.

William McGilvery 1814-1875. McGilvery was engaged in various enterprises including shipbuilding and shipping. From a family of sea captains, he was active in the southern yellow pine trade and did business with Bucksport native Henry Buck in South Carolina. Yellow pine was prized for ship building. McGilvery brought Maine shipbuilders to Bucksville, South Carolina to build the largest ship ever built there. Image courtesy of Penobscot Marine Museum.

McGilvery and Nickels began building Henrietta in 1874, financed primarily by funds drummed up from family and friends back home in Maine. By September of that year, more than 100 shipbuilders from Searsport, Maine, arrived in Bucksville to begin work on the new cargo ship. In advertising for workers, the consortium spiced their message by pointing out that, as opposed to the cold, Maine winters, shipbuilders working in South Carolina would enjoy warm weather throughout the fall and winter.

That message was true to a point, but McGilvery and Nickels hadn’t realized that in South Carolina, September is very much a part of summer. Weather in Bucksville was hot, humid and stifling and many of the Maine men came down with malaria. Despite this unfortunate loss of manpower, the balance of the crew remained healthy enough to finish the project.

To begin, 1.3 million feet of longleaf pine and other woods were cut and milled. From that point on, the Maine men worked from dawn to dark, all winter. And as opposed to the salubrious conditions promised in the advertisements, the winter was cold, wet and quite uncomfortable.

And yet, after eight months, the vessel was completed. The Henrietta was 201 feet long, 39 feet wide and 24 feet deep when loaded with cargo. She was 13 feet deep on launch day. So big and heavy was the ship that in order to keep her from scraping bottom when launched, the builders attached a raft of empty turpentine barrels to her in order to increase buoyancy. Despite these precautions, she scraped bottom several times on her way to deep water.

From Bucksville, the ship was taken to Charleston, South Carolina, where she was rigged with 24 sails and a skysail, the topmast of which, rose 147 feet above deck.

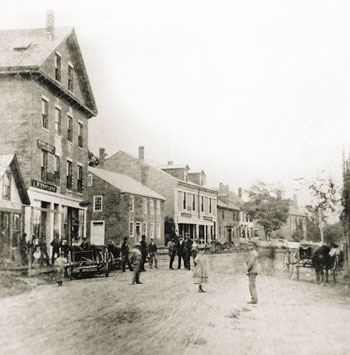

Main Street, Searsport, Maine. This remains the central business area. Miss Lucy Edwards’ millinery and dry goods store would likely have been in this central part of town during the Civil War. The absence of electric poles and gas street lights likely dates the photo to McGilvery’s time. Image courtesy of Penobscot Marine Museum.

Upon entering the merchant trade, Henrietta never returned to South Carolina. For the next 19 years, the vessel sailed the world, carrying cargo to all active ports. She was the last of the great sailing ships to carry tea from China to New York City.

But in 1894, a typhoon ran Henrietta aground off Kobe, Japan, raking her bottom to a point beyond repair. Her fabled southern pine and oak timbers were methodically sawed into small sections and sold as bundled firewood. The only known photo of Henrietta was taken as she lay, derelict, after being run aground and before she was cut up for firewood.

After this, similar wooden shipbuilding was never again carried on in South Carolina. The Henrietta was the largest wooden vessel ever built in South Carolina and was one of the very last square-rigged wooden ships ever built prior to the advent of iron frames and steam power.

The Henrietta built in South Carolina was not the only vessel of that name owned by William McGilvery. Another Henrietta, this one a brig, was built by Marshall Dutch in 1851. A look through ship’s registries of the period will indicate that a number of sailing vessels were also named Henrietta. Henrietta, it seems, was a popular name for sailing ships of the day.

McGilvery Mystery

The pistol that

killed

William McGilvery was

not found in his hand.

William McGilvery never knew of the fate of his prized cargo vessel; he died in March of 1876. McGilvery’s interests were vast and included not only sailing vessels but also, real estate. Had he lived, he would have gone into old age a wealthy man. But gruesome fate intervened. An obituary in the Bangor Whig and Courier newspaper unveiled an unsolved mystery regarding William McGilvery’s untimely end.

The Whig and Courier story reported, “The report of sudden death by a pistol naturally suggests death by suicide, all the circumstances revealed tend to prove the supposition, and those most thoroughly cognizant of the facts are most firmly convinced that the death accidental and entirely unpremeditated. The allegation of suicide is put forward in order to hint at pecuniary embarrassment, and without a scintilla of knowledge of the deceased’s affairs, or a shred of justification, a cold-blooded report is made to inflict the worst possible damage in advance, by assuming insolvency and proclaiming that the “state will not pay twenty-five cents on the dollar.”

City of Georgetown, following it’s maiden voyage to Georgetown, South Carolina, 1902. The 168' vessel was built in Bath, Maine. She made many voyages delivering yellow pine lumber to New England shipyards. Georgetown County Digital Library photo.

The article went on to say that William McGilvery’s son Willie had tried unsuccessfully to shoot some rats with a pistol, but without success. So the senior McGilvery took the pistol and went outside to try his luck. He was later found dead.

While more in-depth facts surrounding this case are lacking, the Whig and Courier also implied that the pistol that killed William McGilvery was not found in his hand, as would likely be the case with a suicide victim.

Also, the question of insolvency is based upon false information. Probate papers indicate that at the time of his death, McGilvery owned sailing vessels, property and more. It took many pages to list all his assets.

So what really happened to William McGilvery? Did he really commit suicide on the spur of the moment, and if so, did the gun fly from his hand as a reflex action after being fired?

In researching this story, nothing was found to suggest murder, opportunistic murder. But murder stands as a definite possibility.

Since the McGilvery’s lived on the edge of town, it is possible that transients could easily have taken short cuts through his property.

And since William McGilvery was not insolvent, as some at the time suggested, why would he, on a whim, kill himself? It was stated that just prior to his death that he was happy, cheerful and working steadfastly on his various business ventures.

William McGilvery’s death certainly ranks as a cold case file. But barring physical evidence, the file will probably remain open indefinitely. Some questions are, did the local authorities save the pistol or even the projectile that killed William McGilvery? How long did William lay dead, outside, before he was found? These and countless other questions could go a long way toward solving this puzzling case.

But in all probability, William McGilvery and his questionable death will remain a local mystery for many years in the future.