Maine Lighthouses

Facts, Myths & Mayhem

by Tom Seymour

Christmas Eve 1886. The British bark Annie C. Maguire, headed for Portland Harbor coming from Buenos Aires, Argentina, crashed on the rocks in a storm at the foot of the Portland Head Light, Cape Elizabeth, Maine. The lighthouse keepers placed a ladder out to the ship for the captain, his wife and 12 crewmen to get ashore. Portland Head Light was the first built under the federal lighthouse project started by President Washington in 1791. Photo courtesy of Maine Historical Society

Images of Maine lighthouses are emblazoned on placemats, tee-shirts, postcards and calendars. But each lighthouse has its own story. And many of these stories are not readily available.

So here, is a selection of some of the more interesting and memorable lighthouse tales, as well as some background information on Maine’s early lighthouses, their keepers and the lives they led.

Light stations, in one form or another, are nothing new to Maine and New England. From the beginning it was clear that rocks, shoals and other navigational hazards were taking a great toll in lives and property. To address that problem, colonists used bonfires, placed on high points in order to warn ships at sea to stay clear.

This method was wanting in several respects. First, the available supply of firewood soon ran out, creating the need to search further afield for fuel. Next, the light from a ground-based light source often didn’t reach far enough out to sea for ships to see and avoid coastal hazards.

Eventually the need for another warning method became clear. Realizing that the higher the light was set, the further out to sea its beacon would shine, colonists began building tall beacons. The same principal that applies to sailors on lookout, high up in the rigging of tall ships, who can see further than those on deck below, also applies to lighthouses.

While the curvature of the earth determines the horizon as seen from sea level, the higher above sea level the further the apparent horizon. This basic assumption was what colonial lighthouse builders used as a general rule. But in the 19th century, mathematicians devised a formula to determine exactly how far a light can be seen at sea depending upon height of the light.

The basic formula calls for multiplying the square root of height above water times 1.23 miles. Using that formula, the light atop a 100-foot lighthouse puts the horizon at 12.3 miles.

It must also be noted that sometimes, the atmosphere acts, through refraction, to increase the maximum distance of a light. It is possible, at times, to see something that lies slightly below the horizon.

Light Sources

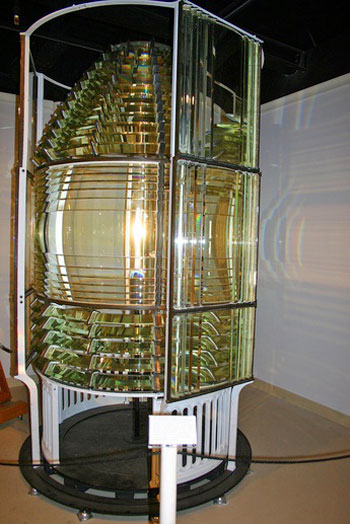

Second generation Fresnel lens. The lens bent, directed and intensified light. In early lighthouse candles were used before whale oil, petroleum and electricity in the late19th century.

Early lighthouses used a number of different fuels to illuminate their beacons. The first lighthouses used candles, their light strengthened and reflected by convex mirrors. Such systems were rated according to “candlepower.”

In the mid-1700s an inventor named Francois Pierre Ami Argand developed a new type of lighting system. Argand’s design used reflectors that heightened the light’s intensity and helped disperse it on the horizontal. Not all the light departed on the horizontal, though. This system allowed a considerable amount of light to shoot up on the vertical. Still, this was a vast improvement over previous systems.

But this system was only employed in European countries. Then in 1812, an American inventor, Winslow Lewis, devised a system similar to Argand’s and sold it to the United States government.

Both Argand and Lewis used oil lamps rather than candles. This, coupled with reflectors, gave American lighthouses the boost that they needed. For 40 more years American lighthouses used the Argand system exclusively.

Unfortunately, a parsimonious director of U.S. lighthouse service saw to it that the Argand system remained in place, despite the debut of a far more effiective system. That system was developed by Augustin Jean Fresnel who, in 1822, developed a lens featuring concentric circles that by way of diffraction, bent the light so that it reached out horizontally. Still, a trifling amount of light was wasted on the vertical, but this was a small matter when compared to Argand’s and Lewis’s designs. The Fresnel lens was the most significant advancement in lighthouse beacon technology ever, at least until the advent of the electrified lamp.

Finally, America owed a debt to sea captain Matthew Perry, who was promoted to Commodore Perry and was the head of the American expedition that opened Japan to world trade, and who brought a pair of Fresnel lenses to America where they were immediately put to use on a New Jersey light station. These proved so effective, so superior to the old Argand lights that the government quickly adopted them and put them to use up and down the eastern seaboard.

To fuel lighthouse lamps, the U.S. Government chose whale oil, a common commodity at the time. But by the mid-19th century, with sperm whales, the source of the oil, decreasing in numbers as a result of over-harvesting, supply-and-demand caused the price of oil to surge. So the government turned to a variety of different sources. These included rapeseed oil, what we today refer to as “canola oil.” But rapeseed oil was not grown in sufficient quantity in America and it was quickly supplemented by more readily available lard oil and in some cases, kerosene. Some stations used mineral oil as well.

But no matter what kind of oil used, lighthouses needed a steady supply and that needed to be delivered in bulk. Storing oil outside could lead to contamination, so “oil houses” were needed for bulk oil storage. Today, we can still see these small, often square, brick structures situated conveniently close to lighthouses.

A typical light station included the lighthouse itself, keeper’s residence, usually a separate structure and the oil house.

Portland Head Light

Portland Head Light, Cape Elizabeth, Maine. The lantern, lit by 16 whale oil lamps, saw first light on January 10, 1791. A ship headed for the horizon is visible in the background. Fishermen’s Voice photo

Portland Head Light carries the distinction of being the first lighthouse to operate under control of the federal government. Prior to that, local economies funded the building of lighthouses. In colonial times, the English monarch filled the gap by appropriating funds to keep “his majesty’s subjects” safe and their property secure.

George Washington, the president of the new United States of America, established the first national infrastructure project with the construction of lighthouses. On January 10, 1791, he appointed a keeper for Portland Head Light. Construction had begun four years earlier, in 1787, when the Massachusetts legislature appropriated $750 to build the lighthouse. This was due to a shipwreck on nearby Bangs Island, which caused the drowning deaths of two persons. Up until that time, there were no lighthouses on the rocky Maine coast. When the U. S. government assumed control of all lighthouses in 1790, Congress provided $1,500 more to complete the unfinished lighthouse.

Washington personally chose and hired two masons from the area, John Nichols and Jonathan Bryant, to build Portland Head Light. Washington pointed out that since the government had only limited funds, the builders should use material from surrounding shores and fields. Much of the rubble used to build the light was hauled on sleds powered by oxen.

However, it was feared that the proposed 58-foot light tower was of insufficient height for its light to be seen over obstructions to the south. Plans were changed to raise the finished height and the newly completed lighthouse rose 72 feet from its base to the lantern deck. The lantern, lit by 16 whale oil lamps, saw first light on January 10, 1791.

But all was not well with Portland Head Light and in 1810, it was determined that wood in the lighthouse as well as the keeper’s house was perennially damp and had begun to rot. This was caused by the lighthouse keeper storing oil in a room in the lighthouse, which added undue weight and stress on the floor. The problem was solved by not only repairing the wooden part of the structure, but also by installing an outdoor oil shed.

Problems continued to plague Maine’s first lighthouse. In November 1812, a contractor, Winslow Lewis, the same Winslow Lewis who had developed the new lighting system that was ultimately used in all U.S. lighthouses, determined that the top 20 feet of the tower was in poor shape.

So in 1813 Lewis had the problematic top 25 feet of tower removed and his new reflector lighting system installed at a cost of $2,100. Although closer to the originally planned height, it still managed to shine its lifesaving beacon out over the dangerous sea surrounding Portland Head.

A year after lamps and reflectors were upgraded in 1851 an inspection revealed that the reflectors were scratched after only one year in service. The house leaked and rats were gnawing on the tower’s underpinning. All these were unacceptable and steps were taken over the next several years to remedy the situation. A fourth-order Fresnel lens took the place of the old lamps and reflectors and a fog bell tower with a 1,500-pound bell was added.

During the Civil War, the tower was raised another 20 feet, thereby assuming something akin to its original height. This was in response to the very real threat posed by Confederate raiders sweeping down on shipping in Portland Harbor. The additional height enabled watchers standing atop the tower to see further out to sea and give early warning of the approach of enemy vessels.

On Christmas Eve, 1886, British bark Annie C. Maguire struck the ledge at the foot of the lighthoiuse and lay on her side. But lighthouse keeper Joshua Strout, along with his wife and son, managed to lay a ladder out to the wrecked vessel and the ship’s captain , master, his wife, two mates and the nine-man crew all managed to escape to safety.

The cause of the wreck was never established. The crew mentioned that visibility was fine and clear and they saw Portland Head Light before crashing on the ledge.

Today, after over 200 years of renovation and change, Portland Head Lighthouse stands 80 feet high and sits 100 feet above the sea.

Cape Neddick Light

Cape Neddick Light. In the foreground, right of the keeper’s house, is the loading ramp down to the boat landing and a roof over a storage shed. The area having had its share of ship wrecks the light house was not always enough to keep ships off the rocks. That may be a result of ledges and currents that made a light necessary. NOAA photo

Every lighthouse has its own stories and Cape Neddick Light owns some of the most interesting. For instance, Voyager II, launched by NASA in 1977 to explore the fringes of our solar system, included material about our earth meant for extraterrestrial eyes only.

One of the pictures that Voyager II took with it to the depths of space was of Cape Neddick Light. With Voyager I already in deep space, Voyager II, already on the edge of the solar system, will soon shed the familiar territory of our solar system and continue its endless journey through boundless space. If and when otherworld civilizations discover Voyager II, they will also learn about one of Maine’s most famous lighthouses.

Lighthouse keepers kept farm animals for food and pets for companionship. James Burke became lighthouse keeper in 1912. Burke and his family maintained a flock of chickens and a cow. Burke also turned to what nature could supply in order to feed his family and to that end, he hunted sea ducks and caught fish. Lobsters were among the Burke family’s regular menu items. Lighthouse keepers were paid low wages and were obliged to be resourceful, as was the Burke family.

Birds of all kinds also landed on the island, but not out of choice. Lighthouses were barriers to bird migration and somehow, flocks of birds managed to crash into lighthouse towers. Lucy Burke, James’ Burke’s daughter, wrote of immense flocks of birds crashing into the light tower at night. Lucy said that the family often gathered hundreds of dead birds in the morning after they had killed themselves by flying into the tower the night before.

As with most lights marking dangerous passages, Cape Neddick Light has seen its share of shipwrecks. This brings up the question of how shipwrecks are possible within sight of a lighthouse. Most of the time extraordinary circumstances were in play. Sometimes wrecks just happened, as with the case of the wreck of the Annie C. Maguire at Portland Head Light.

Cape Neddick Light has seen its share of wrecks. In fact, on Thanksgiving night, 1842, the Isadore crashed into the rocks at Cape Neddick. Everyone aboard perished. This event led the way to construction of the now-famous light. Even today, people say they see a ghost ship, a shade of the Isadore, sailing near the rocks where she had sunk.

On February 16, 1842, the barque William Fales went off course and slammed into the rocks at Cape Neddick. The vessel’s captain, William Thomas, mistook the light from a private residence for the Cape Neddick Light, causing him to steer toward the rocks. A fierce storm had blown in, accompanied by a pea-soup fog.

When Captain Thomas realized his mistake, it was too late to correct his course. The ship’s anchor was insufficient to hold the vessel out from the rocks. The chains snapped and the William Fales slammed into the rocks. The crash ripped a huge hole in the vessel’s hull. The waves retreated, sucking the ship off the rocks. But when the next mountainous wave slammed the vessel it hit the rocks again.

Captain Thomas, pulling a rope, jumped overboard and attempted to make it to shore and secure the rope so others might be saved. Thomas made it to the rocks, but before he could secure the rope another giant wave knocked him off his feet and carried him out and under the vessel. He was never seen again.

Townspeople, realizing what was occurring, did their best to locate and rescue the crew. Despite their best efforts, only five people survived the wreck.

Seguin Island Light

Shoreside approach to Seguin Island Light, 3 miles off Georgetown and Popham Beach. (Photo by H.G. Peabody courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard)

The keeper of the Seguin Island Light, John Polerecsky, wrote on November 11, 1796, I Receivd 25 barrells of oil ... It took four stout men to Cary one barell to the house, and the Same four men and Myself to lift the barell on the top of the Cisterns to empty them, being Six foott high. If I could afford to keep a pair of steers or a horse, I could Save all that trouble & expence in taking the oil on the shore to the house in half this time, but I should run my Self in debt ... I have but one Cow here for my family and one tun of haye I purchased for her, delivered to the house, Cost me 20 dolars and so it is with all the necessaries of life till I Cann Raise them. Therefor hope you will be so obliging as to have My Salary Raised to 300 dollars .... The rocky terrain is shown here in a ca. 1889 photo of the second lighthouse on Sequin Island.

Further up the coast is Seguin Island Light, Maine’s tallest lighthouse. It is also Maine’s second oldest. Seguin Island Light carries another distinction; the original tower was commissioned by George Washington in 1795. Only one contractor, General Henry Dearborn, submitted a bid to build the wooden structure. Dearborn was General of the Maine Militia and served with Benedict Arnold during the ill-fated expedition to Quebec.

In 1820, the wooden tower was replaced by a stone tower. Local stones were a main component of 18h-century lighthouses. In 1857, the stone tower was replaced by the current tower, made of cut stone. This tower has the only first-order Fresnel lens remaining in Maine. Prior to that, the old light station proved insufficient to prevent shipwrecks, as evidenced by the wreck of the Isadore in 1842.

Seguin Island has many superlatives. During the War of 1812, the famous sea battle between the American warship Enterprise and the British warship Boxer took place just off Seguin Island. The cannon fire from both ships could be heard and seen from Munjoy Hill in Portland. The Americans won, but the captains of both ships perished during the battle. They were buried, following a funeral parade through Portland, side by side in Eastern Cemetery on Munjoy Hill.

And then there were those sea serpents. In 1875 the captain and one-man-crew of an unnamed vessel reported that a sea serpent approached their vessel and stuck its head over the rail. The captain directed his crewman to spear the creature with a pike. Following that the serpent slid back into the sea. The head of the pike was festooned with gore from the sea serpent and upon reaching port, the captain showed this to all who cared to see.

Buried treasure, of course, figures prominently in the folklore surrounding Seguin Island. The famous pirate Captain Kidd is reported to have buried treasure on the island and this story persisted until the 1930s, when in 1936 the Bureau of Lighthouses authorized one Archie Lane to dig on Seguin Island for one year. After 12 months of digging all around the island, Lane, who found no treasure, was disheartened. But the legend remains and will probably persist.

In 1985, the Coast Guard contingent that manned the island was withdrawn. After this, those who had served at Seguin reported that as furniture was being packed for transport the following day, the ghost of a past lighthouse keeper stood near the bed of a warrant officer, pleading with him not to take his furniture and to leave his home alone.

The next day as the dory, loaded with furniture, was being let down to the sea the engine stopped and the chain holding the dory broke, sending the loaded dory down to the sea, where it promptly sunk.

Seguin Island has many of these supernatural stories to tell.

Pemaquid Light

Pemaquid Point Light is well known for the many ship collisions it has seen since the earliest colonial times. The wavy striped ledges that run to the sea are visible upper left. NOAA photo

Since the beginning of European colonization, the rocks at Pemaquid Point have claimed countless lives. Commissioned by president John Quincy Adams in 1827, the first Pemaquid Point Lighthouse was built of stone rubble, the same as was used in so many other Maine lighthouses.

A newer version was built in 1835 because sea water, used in the mortar mix, was causing the building to crumble. The contract for the new light stipulated that only fresh water be used in the mix. That tower stands today, a testament to cement mixed with fresh water.

Pemaquid Point light may be Maine’s best-known lighthouse, images of it appearing in nearly every form over the years. But most telling, Pemaquid Light is featured on the Maine quarter and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

A unique feature is the exposed bedrock making a wavy transition from the lighthouse all the way down to the sea. The sediments that formed a gneiss, about 360-415 million years ago experienced intrusion by molten rock. As this hardened, lingering heat and pressure welling up from underground created the wavy, contorted pattern.

As with so many of Maine’s lighthouses, Pemaquid Point has experienced many shipwrecks. A period postcard from 1903 shows a photo of the sailing vessel Sadie and Lillie on the rocks at Pemaquid Point. Another vessel, George L. Edmunds, met the same fate. The culprit was a fierce September storm, whose winds were so powerful that ships were powerless to avoid being swept ashore on the rocks.

Fourteen men from the George L. Edmunds and one from the Sadie and Lillie lost their lives as both vessels piled upon the rocks. Rescue dories were immediately smashed upon being launched, as was the ship’s boat from the George L. Edmunds.

The list of shipwrecks from the 17th century to the present is long and melancholy. Standing on the rocks at Pemaquid Point, it is not difficult to envision the tragedies that have unfolded there.

Fort Point Light

Fort Point Light, Stockton Springs. Off east Cape Jellison at the end of a peninsula ledge that projects into the Penobscot River. The width of the river halved at that point, creating an obstruction and currents. NOAA photo

Not all lighthouses are meant to shine their beacons to ships at sea. Fort Point Light in Stockton Springs is a river light. It is situated on the east side of Cape Jellison at end of the Fort Point peninsula at the narrow mouth of the Penobscot River and across from the Town of Penobscot.

Established in 1836, the first lighthouse was built of undressed granite. Granite was readily available from local quarries. This new lighthouse was built of brick in 1857. Native brick was used in lighthouse and oil house construction up and down the coast and the brickyards of Bangor and Brewer were just upriver from Fort Point. At the same time, a new, wooden-framed keeper’s house was built and attached directly to the tower.

A bell tower was erected in 1890. It was operated by means of a gravity-driven weight that slowly spiraled down a shaft, tripping a hammer that beat on the bell. This pyramidal bell tower numbers among the very few of its kind remaining in the country. The bell tower is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Being keeper of Fort Point Light was a plum job, since the light station was situated on the mainland, making it easy to go shopping and for children to attend local schools. So it’s easy to see why in the years between roughly 1880 to 1930, only four keepers were in residence at Fort Point.

Fort Point Lighthouse has its own unique story. It was the first river light in Maine. At the time of it’s authorization by Congress in 1834 shipping up and down the Penobscot River all the way up to Bangor and Brewer was increasing. The ledge that the lighthouse sits upon was a very real hazard. That, coupled with a fierce rip current at the tip of Fort Point, made it a good place for a light.

Its fourth-order Fresnel lens numbers among only eight still operating in Maine lighthouses. This lens remains in use today, aiding navigation in a treacherous section of the Penobscot River.