When the Fix is In

by Nicholas Walsh, PA

It is difficult for a

lobsterman to compete

on quality, so the major

factor determining

the price a dealer will offer

is consumer demand.

When a company establishes the terms of a sale, it cannot do so in coordination with other companies in the same business. Price fixing is an agreement among competitors that raises, lowers, or stabilizes prices, or that coordinates competitive terms. The agreement can be written, verbal, or just an understanding – a “wink and a nod.”

Price fixing is prosecuted as a criminal federal offense under Section 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Criminal prosecutions are generally brought by the U.S. Department of Justice, but the Federal Trade Commission also has jurisdiction for civil antitrust violations. Many state attorneys general, including Maine’s, also have antitrust divisions. Private individuals or organizations may file suit for antitrust violations, and can recover triple damages as well as attorney’s fees. It’s law with serious teeth.

A plain agreement among competitors to fix prices is almost always illegal, whether prices are fixed at a minimum, maximum, or within some range. Illegal price fixing also occurs whenever two or more competitors coordinate shipping fees, warranties, discount programs or financing rates. But it doesn’t end there: Illegal anti-competitive activity can also include designating sales territories, promotion and payment of employees, production capacity and lots of other factors, even how much each competitor will spend on research and development.

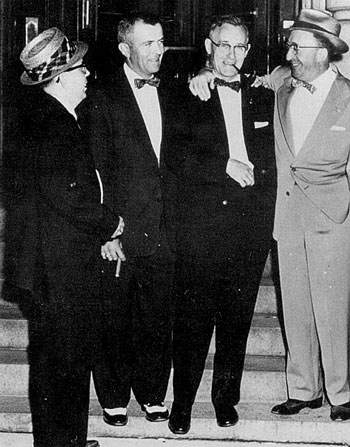

Left to right: John Knight, Rodney Cushing, Leslie Dyer, and Alan Grossman at the federal courthouse in Portland. The picture was probably taken during the price-fixing trial in 1958. Photo courtesy of Barry Faber. The Great Lobster War, Ron Formisano, courtesy University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, Mass. (See Feds Indict MLA, Fishermen’s Voice archives, September 2007.)

A few years ago a bunch of New England private colleges routinely traded certain financial aid information so that each school would offer roughly the same amount of financial aid to similarly placed students. They did so, they said, so that that money would not be a factor when such students chose a college. Very nice. But this was illegal activity, as the Department of Justice pointed out. If a school wanted a certain student to attend, the school ought to compete for the student in the educational marketplace, by offering a better deal than competing schools.

Not all price similarities, or price changes that occur at the same time, are the result of price fixing. On the contrary, they often result from normal market conditions. For example, dealer prices for lobster vary little between dealers because lobsters of a specific grade or shipability are a commodity, essentially identical. It is difficult for a lobsterman to compete on quality, so the major factor determining the price a dealer will offer is consumer demand, which is about the same for all dealers. It is easy to suspect collusion between dealers as to price or other terms, and perhaps that has from time to time occurred in the long history of Maine lobstering, but economics explains why dealer prices are so often close.

So what factors may indicate price fixing? For one, closely similar prices between competing businesses, especially for a long period of time. Another is difficulty in getting a company interested in making a sale to you, or, if it will respond, making ridiculous offers that you would never accept. Another possible indicator of collusion as to territory is that, if you are looking for goods or services, you may always hear only from one company.

Not everyone is a genius: you may even receive similar or identical letters from different companies explaining price changes. If you tell a business that you are going to seek a competing offer, you may hear “They won’t offer you a better price.” If you regularly solicit bids for services, watch out for regularly alternating low bidders, or bids that are suspiciously close, or bids from various competitors that are laddered, the bid amounts differing by the same amount.

And don’t do it yourself. If you are communicating with others in the same business and the talk turns to prices, terms or territory, be aware, be good - and be careful.

And stay out of trouble.

Nicholas Walsh is an admiralty attorney with an office in Portland, Maine. He may be reached at 207-772-2191, or nwalsh@gwi.net.