Ecosystem Approach Viewed as Vital for Menhaden Management

by Laurie Schreiber

“The board has long

recognized the

importance of

Atlantic menhaden

as a forage fish.”

– Nichola Meserve,

Atlantic Menhaden Board

ARLINGTON, VA.—At its May 5 meeting, held by video-conference, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) continued its deliberations on the complicated topic of managing Atlantic menhaden as one part of a complex ecosystem—specifically, as an important forage fish.

In February, the ASMFC accepted a report from its Atlantic Menhaden Board that said the ecological management approach indicates that fishing for menhaden should be lower in order to account for its role as a forage fish, even though the single-species management approach indicates the stock is not overfished and overfishing is not occurring.

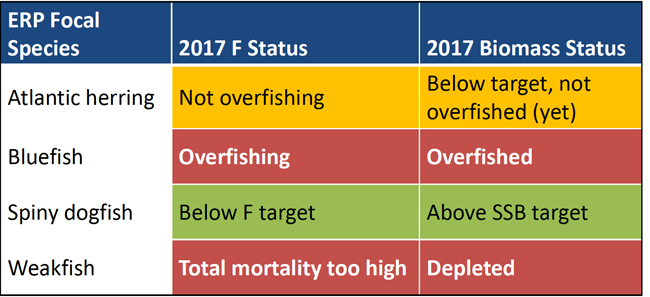

At that time, the board tasked an Ecological Reference Point (ERP) Workgroup with producing several scenarios to explore how different fishing mortality assumptions for other predator and prey species—specifically, bluefish, weakfish, spiny dogfish, and Atlantic herring—might affect menhaden fishing mortality targets under the ecological approach.

In a February news release, the board’s chair, Nichola Meserve, said, “The board has long recognized the importance of Atlantic menhaden as a forage fish for a variety of predators as reflected in its setting of conservative harvest limits for menhaden and its emphasis on the development of ERPs as one of its highest priorities for managing the species.”

The ERP assessment is an important step toward achieving ecosystem-based fishery management, she said.

This chart shows the status of various species under consideration in relation to an ecosystem-management approach for Atlantic menhaden. Courtesy of New England Fishery Management Council.

According to the release, under the traditional single-species reference points, Atlantic menhaden are neither overfished nor experiencing overfishing. Population fecundity, a measure of reproductive capacity, has been above the single-species threshold since 1991 and above the single-species target in 20 of the 27 years since then.

Fishing mortality has remained below the single-species overfishing threshold since the mid-1970s, and below the single-species overfishing target since the mid-1990s.

Although the ERP assessment indicates that fishing mortality should be lower than indicated under a single-species management plan, it also showed that the conservative total allowable catch set for the 2018 to 2020 fishing seasons is consistent with fishing targets under the ERP management scenario.

The ERP assessment was based on the Northwest Atlantic Coastal Shelf Model of Intermediate Complexity for Ecosystems, or NWACS-MICE. The model allowed scientists to explore the impacts of predators on menhaden biomass and the effects of menhaden harvest on predator populations.

“Their profound impact

on the health of the

ecosystem cannot

be overstated.”

Garrison Duke Gosney

The model focused on four key predator species—striped bass, bluefish, weakfish, and spiny dogfish; and three key prey species—Atlantic menhaden, Atlantic herring, and bay anchovy. The species were chosen because diet data exists that indicate interaction between the species, according to the release.

The ERP assessment sought to strike an equilibrium by using a combination of single-species and ecological management tools in order to evaluate trade-offs between menhaden harvest and predator biomass.

An important conclusion from the ERP assessment was that a final determination for the appropriate harvest level for menhaden depends on management objectives for the ecosystem—both menhaden and its predators, the release said.

The exercise involved weighing multiple factors in a dynamic system that includes predator/prey relationships between the species themselves, as well as humans impacts from harvesting both predator and prey species.

For example, the ERP Workgroup developed an example ERP target that seeks to balance maximum fishing on menhaden while it also sustains striped bass biomass when striped bass is also fished at its maximum.

The group concluded that, to meet current striped bass management objectives, the fishing target and threshold for Atlantic menhaden should be lower than the single-species target and threshold.

The group developed a variety of scenarios that sought to show how fishing impacted the biomass of the various species in such a way that it also impacted the forage role of Atlantic menhaden and Atlantic herring.

The work was further complicated by uncertainty of the data. For example, the model predicted a higher consumption of Atlantic herring by striped bass than diet data seemed to indicate.

“While an important component of striped bass diets, the model may be overestimating the importance of Atlantic herring on a coastwide, annual level,” the group’s chair, Matthew Cieri, said in his presentation to the ASMFC.

“When you start looking at ecological-base fisheries management, when you start drawing in multiple species as predators, you also have to draw in multiple species as prey,” said Cieri.

Predators, he explained, have the ability to swap from one small fish to another. The working group, he added, is prepared to take a deeper dive into the various components of the ecosystem model, such as seasonality and geography, all of which might contribute to modifications of fishing and biomass reference points.

It’s important, he said, to understand all of the factors going into the ecosystem-based management approach, particularly for federally managed species, which by law have to be rebuilt.

“The tradeoffs between Atlantic herring biomass and menhaden removal is something that the board has to examine,” he said.

Cieri said the group recommended the following additional analyses:

• Explore alternate Atlantic herring biomass scenarios given the uncertainty in future recruitment

• Explore sensitivity to model parameterization of the Atlantic herring/striped bass relationship

• Explore scenarios where other ERP focal species are fished at their single-species fishing mortality reference points

After Cieri’s presentation, one ASMFC member noted that goals around fishing for menhaden as well as maintaining a sustainable biomass depend in part on the biomass Atlantic herring, also an important forage species.

“When we discuss next steps, I’d like to understand the outcomes of each next step,” she said. “Because this is so complicated and we could travel down a rabbit hole, it would be good for us to understand what the discrete pieces of information are that the board can then apply to its next management decisions.”

Overall, said ASMFC members, the ecosystem approach is designed to evaluate tradeoffs around managing multiple species.

However, said one member, “Everything said up to now implies we plan to keep tinkering with inputs. Is the working group planning to produce a summary of decision options that the non-scientists and the public might be able to understand? We’ve worked on this a long time and the expectation is to make a decision in August.”

Members of the working group said the plan is to have materials available before the board’s next meeting in August.

The board received a May 5 electronic communication from Virginia resident Garrison Duke Gosney who said that menhaden are the sole keystone species of the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic seaboard.

“Their profound impact on the health of the ecosystem cannot be overstated,” he wrote. “An unbridled population is essential for water quality, pollution control, erosion control, and the prosperity of every marine, wetland, and vegetative specie that live therein. Menhaden therefore should be analyzed not a single species but as the ecological kingpin of interrelated species. They should not be managed for the profitability and survivability of a single industry, but rather for the health and proliferation of the entire Atlantic marine ecosystem.”

The reduction industry, he wrote, could go on for some time catching about the same number of menhaden each year due to high harvest caps and increasingly productive technologies. However, he said, “From an ecological point of view, there is simply no downside to limiting or even banning the industrial slaughter of menhaden….The ASMFC should support a management option that ensures striped bass and other game fish have abundant forage, and that menhaden are allowed to fulfill their foundational role in the marine ecosystem, even if that means a substantial decrease or abolishment of industrialized reduction fishing.”

The ASMFC received another communication from Chesapeake Bay resident Tom Lilly, who wrote that the allocation of menhaden for industrial reduction “is destroying the ecology of Chesapeake” and “is negatively affecting many hundreds of thousands people and businesses” including charter business and finfish watermen that in turn support crews, wholesalers, distributors, markets, restaurants, boatyards, and marinas.