Fishing communities from Maine to India are fighting against industrial aquaculture – particularly shrimp and salmon – and factory style, industrial fishing operations. Many of the Asian fishing communities affected by the tsunami have historically presented a nearly impenetrable fortress that has repeatedly fended off efforts for expansion of shrimp farms and issuance of joint-venture permits to distant-water industrial fishing fleets implicated elsewhere in large-scale over-fishing and marine ecosystem damage, as well as displacing fishing communities.

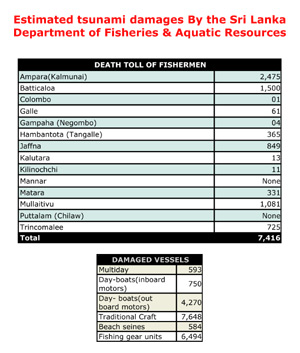

Although fish is an important source of protein in Sri Lanka, comprising 60 percent of the population’s total animal protein intake, Sri Lanka exports add up to only $100 million (U.S.). What is exported is caught primarily by 32 percent of the fleet, made up of larger, multi-day vessels, most of which were at sea at the time of the tsunami.

Sri Lanka isn’t a huge player in the game of global seafood trade. The country’s fish production for 2003, including aquaculture and inland fisheries, was barely 285,000 metric tons.

But already, reports of interest by the industrial fleet are being heard from different corners of the world.

Faced with fisheries troubles and excess capacity for years, the European Union (EU) is offering to send its excess fishing capacity – made up primarily of industrial trawlers — to the affected countries. Similar proposals have been floating in several EU member states, including the U.K. and France.

In a memo to those interested in rebuilding tsunami-affected fishing communities, Sebastian Matthew, an advisor for the International Collective in Support of Fish workers (ICSF), cautions against such transfers, calling them “misplaced logic.” He goes on to say that “fishing vessels are one among several requirements needed for fishers to resume normal lives based on fishing. You need fishing gear, ice, and fuel for fishing vessels, frozen-storage facilities, workers on board, and fish consumers. You need harbors and fish-landing centers. In places like Aceh, Indonesia, and in Sri Lanka, you cannot separate fishing from starting lives in coastal areas all over again. You cannot see fisheries and fishing communities in isolation.”

Some, including Matthew, express some suspicion about this apparent gesture of good will by the EU and some of its members. Matthew, for example, wonders whether some countries offering boats aren’t just dumping their excess capacity on the tsunami-affected states.

The Coalition for Fair Fisheries Agreements (CFFA), warns the EU’s offer might lead to negative economic and environmental consequences for countries such as Sri Lanka, which could be on the receiving end of the boat transfers. CFFA is a Brussels-based non-governmental organization, “working for fundamental change in the EC’s policy towards fisheries agreements with countries in the South.” Pointing to a 2000 assessment commissioned by the EU on the matter, CFFA warns that the EU has been looking for a solution for its excess capacity long before the tsunami.

According to the EU study, vessel transfer agreements subsidized by the EU would include a guaranteed supply to the EU market and maintain EU employment in the processing sector. Such provisions could undermine local markets for fishermen’s products and take away much-needed processing jobs often occupied by women and where much of the value is added to the fish, increasing its price in the seafood market.

Fishing gear run aground in Tangalla Harbor.

Photo courtesy of sarvodaya.org. |

Instead of such technology transfers, Matthew suggests, “if people in rich countries would like to help the rehabilitation and reconstruction of the fishing economies of affected countries, they should consider making cash offers, monitor how the money is spent, and put pressure on governments and multilateral bodies to deliver on schedule, so that precious little time is lost in rebuilding the ravaged livelihoods of coastal communities.”

Menakhem Ben-Yami, an independent fisheries advisor based in Israel, acknowledges that maybe some of the larger boats that were lost or damaged by the tsunami could be replaced by northern countries. However, he is one of many who believe that donors should focus on projects that “would heal without hurting the affected fishing communities.” He suggests re-rigging the traditional fishing techniques instead of replacing them with “expensive fishing boats of foreign construction not tested for local conditions.”

“What I’m afraid of,” says Ben-Yami, in a statement available on ICSF’s website, “is that a large EU trawler brought over to an area with many fisher-folk casualties will end in the hands of that or some other corporate bigwig, manned by a skipper and engineer from out of the country affected, and crewed by cheap labor, imported from outside the affected communities. Such trawlers would compete over the fish stocks against the local fisher-folk struggling to revive their fishery and their communities,” says Ben-Yami.

In Sri Lanka, as well as other countries in the region, grass-roots fishing-community organizations are rebuilding their communities. Many are affiliated with the World Forum of Fisher People (WFFP), whose membership spans most of the affected countries.

Four WFFP member organizations — National Fisheries Solidarity (NAFSO), United Fishermen and Fish workers Union, Women’s Development Federation and National Union of Fishers, are based in Sri Lanka, and working on rebuilding their communities.

During a press conference on January 25, 2005, marking the end of a tour of Sri Lanka by WFFP leaders, the organization expressed concerns about the level of immediate relief offered to affected communities and proposed future rebuilding plans.

The organization questioned whether aid monies are being used effectively, stating that, “even after a month, the debris and shattered houses are still kept untouched. The victims are in different camps without any proper cover from rain. No cleaning up has started.” The WFFP emphasized the need for water, dry rations, sanitation, and shelter.

In addition, in a statement issued by Father Thomas Kocherry, member of the WFFP’s Coordination Committee, WFFP warned that “the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund are trying to make use of this tragedy for building up private enterprises, express highways, and tourism.”

“Yes, we agree that the victims have to be shifted to safer places beyond 200-300m away from the high-tide line,” Kocherry’s statement goes on to say, “but the empty beaches are meant for the fishing communities to keep their fishing implements, repairing sheds, fish drying, etc. Please do not build tourism and hotels instead of fishing communities.”