“There’s so much juvenile haddock out there, the mid-water boats can’t get away from it. We’ve got to give them something.” Rice said.

Chart: NEFMC |

The Fork In The Road

As Rice spoke, the sound of a pump started up and the Sunlight off-loaded her herring into a waiting bait truck. According to NEFMC documents, the O’Hara’s sell 90 percent of their herring as bait. Like Rockland, the Massachusetts ports of Gloucester and New Bedford, along with Cape May, New Jersey, to a lesser extent, have come to rely on herring in the absence of groundfish.

“There’s what, 350 million pounds of herring out there?” said Vito Calomo of Gloucester, Mass. “We saw this coming in 1995, we saw the resource coming back and I said to the council, ‘we need a plan, we need to get ready for when the boats start fishing these herring.’ But they said, ‘No. Nobody’s fishing them.’” As groundfish fleets struggled, so did waterfront infrastructures. Calomo and many others saw the future of their ports in the burgeoning stocks of Atlantic herring, Clupea harengus.

“We lobbied to get the infrastructure built that could handle these fish,” said Calomo. The City of Gloucester maintained a working waterfront and promoted the development of multi-million-dollar herring-processing facilities. In New Bedford, a west coast company, NORPEL, came to town and poured $30 million into boats, processing and storage operations for frozen herring intended for the food and bait markets. “Today, for the first time in history, our frozen herring are accepted in the world market,” said Calomo, noting that more value-added facilities were being sought, with an eye on the European market.

As Massachusetts and New Jersey have developed markets for fresh frozen herring, Maine has remained focused on traditional uses of herring — sardines and bait. If fresh-frozen herring processors open more lucrative markets and bid up the price, Maine’s lobstermen will feel the strain.

Bycatch

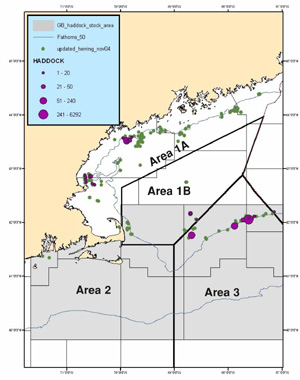

Rice and others have been fighting to keep the mid-water trawl fleet out of Maine’s coastal waters. Calomo, speaking for the interests of Gloucester, supports the status quo. But the competing visions for the fishery have been complicated by the appearance of a huge haddock year class, estimated at four million fish, which showed up last year on Georges Bank. Vessels trying to fish there, in the late summer of 2004, brought in thousands of pounds of illegal haddock as bycatch. Groundfish fishermen expressed outrage that the stocks they had sacrificed so much to rebuild were being sold as lobster bait.

In order to deal with the bycatch issue, the NEFMC, against the advice of science, and its own ad hoc bycatch committee, recommended a 1000-pound haddock trip limit for boats in the herring fishery, with the stipulation that the haddock could not be sold for human consumption. The ad hoc committee had asked for a bycatch cap of one percent of the total haddock quota, which would have shut down the herring fishery in certain areas if boats landed 95 percent of bycatch quota.

“I thought the emergency was that these boats were catching haddock,” said Peter Baker of the umbrella group CHOIR (the Coalition for the Atlantic Herring Fishery’s Orderly, Informed, and Responsible Long-Term Development), which represents many groundfishermen. “The council acts as if the emergency is to keep these mid-water boats fishing, no matter what.”

With so many industries and ports dependent on herring, Rice acknowledges as much. “There’s so much juvenile haddock out there, the mid-water boats can’t get away from it. We’ve got to give them something,” he said. Rice expressed concern that if the mid-water boats did not get some sort of bycatch allowance on Georges, “they’ll be in 1A pounding the resource.”

But the trip limit has many problems. Bill Overholtz, a lead scientist at the New England Fishery Science Center in Woods Hole, believes the trip limit is bad for the resource, and, more importantly, bad for science. “It can generate interesting behavior,” he said, noting that fishermen who saw too much haddock in their catch might be inclined to dump it. “With a cap, they can land it and it will count against a quota,” he said. “Fishermen will have more freedom, they can communicate and work together, and we’ll get more information about what’s really happening.”

Even some of the mid-water trawlers expressed dismay at the trip-limit solution, “The committee asked for a bycatch cap,” said Peter Moore, a spokesman for the New Bedford based company, NORPEL. “Our captains tell us that a trip limit will be unworkable, but I guess the Rockland boats are willing to give it a try.”

Vito Calomo believes the trip limit will work as an emergency measure. “The council recommended a trip limit, so let’s go with that,” he said. According to Calomo, the groundfish crisis has passed, and rebounding stocks can withstand some bycatch. “When we said, ‘no bycatch’ back in the 90’s, there were no groundfish; now there’s millions of haddock out there.”

But diverse groups such as CHOIR, the Recreational Fishermen’s Alliance, NORPEL, and environmental organizations such as Oceana, have all called upon the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to reject the council’s recommendation and implement a bycatch cap.

“We went down to Washington in April and talked with Rebecca Lent [NMFS’s title],” said Gib Brogan, Oceana’s New England spokesman. “We laid out our case and made clear our hopes that they would obey the law calling for a reduction in bycatch.” Brogan’s reference to the law indicates what many observers believe is the organization’s intent to sue if the trip limit goes through.

Maine’s coastal herring fishery is a night fishery. Here the sardine carrier Double Eagle, loaded with herring from a purse seiner, waits to unload at Vinalhaven. Photo: Paul Molyneaux |

Buffer Zone

As Dana Rice said, mid-water boats shut out of the haddock-rich waters of Georges Bank would fish more in the Gulf of Maine. He and many others see that as a catastrophe in the making. “This is the only area where the TAC gets caught,” said Rice. His concern is that the mid-water fleet will catch the 1A quota before the lobster season takes off in the fall. But regulators have refused to exclude the powerful trawlers from Area 1A, and other stakeholders — particularly tuna fishermen and whale watchers — have joined the battle. Both groups claim that mid-water trawlers tear through herring schools at high speed, breaking up the concentrations needed by wild predators. If the herring are scattered, they say, whales and tuna will not come near shore to feed, and both industries will suffer.

Bill Overholtz estimates that natural predators take three times more herring- than the fishery, highlighting the importance of these forage fish to the ecosystem. But Overholtz does not blame mid-water trawlers for the scarcity of whales or tuna nearshore. “There are a lot of variables at play,” he said. “We have many indications that there were large numbers of herring inshore last year. I think it is a matter of availability elsewhere, and other factors.”

A wide range of stakeholders, including NORPEL, supported an 11th hour compromise alternative to Amendment 1, which would limit the mid-water boats to two trips per month in area 1A, and move up the limited entry control date to include the NORPEL boats — which arrived late in the fishery. “This is a big wedge in the mid-water trawl community,” said Rich Ruais, executive director of the East Coast Tuna Association (ECTA). “They are recognizing that our issues are valid,” said Ruais.

But Rice sees no need to compromise. “Two trips a month times 25 boats is still 50 trips a month. That’s no compromise for me. The mid-water boats were built to work on Georges and that’s where they ought to stay,” he said.

Stock Assessment

The rich stocks on Georges have proven elusive, however. After a 40,000-ton harvest in 2002, landings from Area 3 have dropped, adding fuel to the debate about the accuracy of the NMFS stock assessment. The Canadian assessment of the same stock shows it to be 600,000 tons, three times smaller than U.S. estimates, a significant difference.

“I think what fishermen are seeing supports the lower estimate,” said Rob Stephenson, of the St. Andrews Biological Research Station in New Brunswick, Canada.

Overholtz contends that landings data is an unreliable indicator of stock size. He blames the low landings on resource availability. “These fish are very responsive to temperature and other factors, they move around; we’ve been sampling for 40 years and we’re seeing herring now in all major prey species. There’s a big stock out there, they’re just not finding them.”

So far, scientists on both sides of the border have agreed to disagree, but regulators and investors need accurate information. The scientists plan to meet this summer and reconcile the assessments one way or the other. The difference, according to Overholtz, is that the Canadian model, ADAPT, looks more at historic information, while the U.S. model, KLAMZ, looks more at current data, namely acoustic surveys. Acoustic surveys measure abundance using sonar readings: the same information fishermen use to find fish.

Dana Rice expressed skepticism about the new methodology. “If they can’t tell the difference between a haddock and a herring, how do they know what they’re counting?” he asked. “I’ve been looking at this fishery for a long time, and from what I’m seeing now, it doesn’t look good.”

Added risk comes from the fact that Area 1A herring overwinter in Area 2, off the mid-Atlantic coast; if fishing increases there, warned the NEFMC’s advisors, it could lead to overfishing Maine’s inshore stock. Despite those concerns, however, regulators set the 2005 quota for 1A at 60,000 metric tons. “That’s the harvest level this fishery has historically supported,” said Overholtz.

Coming To Terms

Where management will take the herring fishery this year remains uncertain. The NEFMC faces the daunting task of balancing the concerns of outraged groundfishermen, who have sacrificed, only to see their future harvest sold as lobster bait; tuna fishermen and whale watchers, who need concentrated herring stocks to draw in the prey species they depend on; environmentalists, determined to protect the ecosystem, and fishing ports all along the east coast that need herring to keep them viable. If fisheries history is the guide, then experience has shown that the capacity of the herring stock to meet these competing needs will be adjusted downward. As a result, the allocation battle for the resource will intensify.

At a meeting on May 23, regulators talked about a solution that has been on the horizon for several years: shifting the entire regulatory regime to quota management. Individual transferable quota (ITQ) management, which would allocate specific shares of an overall herring quota to historical users and let them trade those shares. The same could be done with bycatch quotas. Theoretically, the most efficient harvester would end up with most of the shares. ITQs would enable “the market” to do the allocation job. Access to various areas could become a moot point in an arena where the victor takes the spoils.

ITQs appear as a simple way to untangle the rat’s nest of competing interests, but Vito Calomo expressed concerns about quota management. “It’s easier, sure. But with ITQs, you could end up with five boats owning the fishery. The little communities on the coast of Maine would be shot.”

While the many concerns about a shift to quota management in the herring and other fisheries go beyond the scope of this article, some observers warned that as a solution, ITQs must be approached thoughtfully. Even Peter Moore, who represents a port and industry that could benefit from ITQs expressed his doubts. “I’m not happy with a winner take all situation,” he said. “ITQs don’t work for everybody.”

“It’s not the ‘Q’, we worry about,” said Peter Baker, of CHOIR. “We’ve got quotas now. It’s the ‘I’ and the ‘T.’” Baker points out that several criteria must be in place regarding individual allocations, the “I” and transferability, the “T.” Otherwise quota management could destroy communities and resources. “If small coastal communities bury their heads in the sand, it’s going to be rough,” Baker warned. “They need to get involved in allocation.”

“There’s a light at the end of the tunnel,” Rice said of the current situation. “It’s a freight train coming at us with ITQs written all over it.”

|