Give Swordfishermen A Break

by Paul Molyneaux

Swordfishing, a tradition practiced by generation after generation of New England fishermen who hunted the giants of the species with harpoon, is now the focus of some well-financed conservation groups. The "Give Swordfish A Break" campaign, organized by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and Sea Web, a project of the Pew Charitable Trusts, aims to force U.S. regulators and fishermen to take aggressive action to rebuild depleted swordfish stocks.

New England's harpoon fishery, in decline since the advent of longlining in the early 60's, was dealt its death blow by the institution of the Hague Line in 1984.  This dividing line between U.S. and Canadian waters cut American boats off from their last productive grounds, the Northeast Peak of Georges Bank. This dividing line between U.S. and Canadian waters cut American boats off from their last productive grounds, the Northeast Peak of Georges Bank.

The Irene & Alton, owned and operated by Bernard Raynes out of Owl's Head, was Maine's last boat to go to Georges strictly to harpoon swordfish. She came home in August of 1985 with one fish after ten days out and Raynes took the top mast and pulpit off for good.

Others such as Richard Stinson, who fished his boat the Ocean Clipper out of Point Judith, Rhode Island, kept at it and even had a few good trips in the late 80's. But he finally sold his boat in 1991 and now only goes after swordfish incidentally.

"We go now almost just for the nostalgia of it," says Stinson, who started swordfishing when he was 8 years old.

The harpoon fishery is basically extinct. The longliners have dominated swordfishing by a large margin since the 70's and currently land 98% of the U.S. quota. They and federal regulators are being targeted by the Give Swordfish A Break campaign, a well-organized consumer and restaurant boycott of swordfish.

Lisa Speer, NRDC's spokesperson for the campaign sees it as a way to bring consumer attention to the plight of fisheries in general by focusing on the swordfish in particular.

"Swordfish are one of the fastest declining species in the sea," says Speer, citing that swordfish don't breed until they reach 150 lbs., yet the average weight of fish being landed has dropped from over 266 lbs. in 1963 to 90 lbs. in 1995. And current estimates indicate the stock is 42% below that necessary to produce maximum sustainable yield. But, as Speer also points out, "these fish are prolific breeders if they get the chance, and with the right conservation measures could bounce back very quickly."

No one questions that stocks are hurting, and the fact that one of Maine's top longliners has moved his boat to Brazil with no plans to return is indication enough of the state of the fishery.

Speer sees this campaign as a help to future fishermen. "If there are more fish everyone will benefit," she says. "Commercial fishermen stand the most to gain from this."

"I wish them well," Bernard Raynes said of the campaign, "but they're not going to bring anything back if there's nothing for them to eat. They have to start with the feed, the herring, pogies, squid, and whiting."

Bernard comes from several generations of fishermen and he and fishermen like him see the big picture. They know that trying to micro-manage one fishery without regard to any others is foolhardy at best and catastrophic at worst. It's only common sense that if you want to rebuild stocks you have to start at the bottom of the food chain not the top.

"Well we've got to start somewhere," says Speer, noting that the NRDC is working on other fisheries. "Our objective is really to let people know that something is going on out there and to get consumers to use their buying power to register their views."

Among other actions Give Swordfish A Break is pushing for area closures, and reduced soak time for longlines so that non-target species such as sea turtles, marine mammals, and undersized swordfish, can be returned to the water alive.

In addition to advocating conservation measures within the existing management system, many of which are supported by the industry, NRDC and Sea Web are also seeking changes in the Atlantic Tunas Convention Act (ATCA). They want U.S. regulators to be allowed to reduce quotas to levels below those negotiated by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). Under ATCA, U.S. regulators must allocate the entire ICCAT quota.

The American industry sees no sense in such action, pointing out that other nations will gladly catch whatever we sacrifice.

"This isn't about conservation," says Nelson Beideman, executive director of the Bluewater Fishermen's Association (BFA). "It's about making money through crisis mongering. Sea Web doesn't acknowledge that ICCAT has now set quotas aimed at rebuilding stocks. Yes, we have a long way to go. Yes, we need a stronger rebuilding program. But why doesn't Sea Web help us get compliance to existing agreements instead of attacking ATCA which is in place to provide some level of assurance that U.S. fishermen aren't sacrificed to foreign interests."

John Hoey of the National Fisheries Institute, and U.S. delegate to ICCAT, regrets that swordfish have become the center of controversy.

"U.S. fishermen have led the way in implementing restrictive measures," says Hoey. "We established a minimum size and the number of small fish taken has dropped 35% since 1989-90. We've agreed to quota cuts. We've been fighting for limited entry for 4 years. We've called for tighter reporting on imports, and trade sanctions against nations that fail to abide by ICCAT agreements. U.S. and Canadian fishermen have done more than any other nations and as a reward they're being attacked in the market place. The people this campaign is hurting are the poor bastards who've called for and abided by the strictest conservation measures of any country."

As far as the harpoon fishery is concerned, Hoey sees it as an anachronism whose time has gone by. "The harpoon fishery, when it existed, was working on a very robust, nearly virgin stock. At its height it took only about 4,000 tons a year. The longline is simply more effective and lots of harpooners switched over. We think swordfish stocks could, at optimum levels support a sustainable harvest of between 12,000-15,000 tons and longlining is necessary to fully exploit this fishery. We'd like to see a viable harpoon fishery return, but harpooning is an incredible amount of effort for the return, and the fish don't even act in a way that makes harpooning possible in many areas."

Much of the current fishery takes place in the mid and southern Atlantic where fish seldom bask on the surface as they do when they reach the waters off New England.

Nelson Beideman, goes so far as to say that it wasn't really longlining that displaced the harpoon fishery. He asserts in BFA literature that New England's harpoon fishery was displaced in the 40's and 50's by the Canadian harpoon fishery, and cites statics showing that by 1960 U.S. harpoon landings were down to 400 tons while Canada's were up to 4,000 tons.

What's happened to Canada's harpoon fishery since then? Although some U.S. regulators claim Canada's harpoon fishery is still strong, the numbers from Canada's Department of Fisheries and Oceans don't agree.

Greg Peacock of the DFO in Nova Scotia says, "Swordfish stocks are definitely in decline, catches and quotas have been dropping since 1985." He points to statistics that indicate only 93 tons were taken by harpoon in 1996, the last year from which numbers are available.

Jim Crawford a longtime harpooner and spotter plane pilot now living in Nova Scotia, was amazed when presented with Beideman's views.

Crawford went harpooning for two months last season and landed only 15 fish.

"Longlining decimated this fishery," he says. "I went on trip with Lewis Larson in 1980, harpooning and longlining. We set the longline three times, and I'm glad I was there to see it because it confirmed everything I'd heard. I saw it all, the turtles, the small fish, all stone dead. They'd take fish down to ten or twenty pounds and sell them to people to mount them.

"Guys would come in with trips of 500-700 fish, but how many of them made the mark [100 lbs.] ? Not many. The average fish was about 70 pounds. Not even old enough to spawn. With harpooning you only take the big fish. I've seen guys pull the harpoon at the last minute because the fish was too small, it's a code of honor, you'd be ashamed to stick a small fish.

"The people who run the restaurants who are endorsing this campaign need to look back and examine their own souls, too, because they were the ones who wanted the small fish. If we came in with one 400-pound fish and six 70-pound fish the restaurants would take the 70 pounders every time because they're easier for them to handle and they make the right size portions. They need to see the light too, that you can't go to the woods and shoot all the fawns and expect there to be any deer left and it's the same with swordfish. What they need to do is stop longlining and in return for that harpooners could give up using spotter planes."

Richard Stinson echoes Crawford's views in some respects, but is more sympathetic towards the longliners.

"It would probably help the swordfish," he says of the boycott. "But those guys [longliners] still have to make a living. I wouldn't want to see them shut down."

Stinson's grandfather sailed out of Swan's Island, Maine on a lumber schooner and landed in Block Island, Rhode Island where he started swordfishing in the late 1800's. Stinson himself started going with his father in 1954. He worked hard to keep the harpoon fishery viable but ended up discouraged with the management process.

"You go to all those meetings and try to work things out and in the end they just do what they want. My log books represent years of research, but to the scientists they're just fish stories. Under Magnuson-Stevens the industry was supposed to have an important role in management, but that's not the way it's working out."

Stinson sees well organized and well funded interest groups getting what they want whether it makes sense or not.

"Sooner or later they're going to figure out that you can't set all those hooks and catch 100-pound fish and expect there to be anything left."

Stinson sees area closures, a limit on the number of hooks a boat can set, and a days-at-sea program similar to what Maine draggers operate under as a good start towards rebuilding swordfish stocks. Like almost everyone who has gone harpooning he would love to go back to it the way it was.

"I've done it a long time," he says. "I miss it."

Nonetheless, Bernard Raynes doesn't foresee putting the mast and pulpit back on the Irene & Alton anytime soon. As he said, if you want to rebuild any stocks you need to start at the bottom of the food chain, not the top. And that could take more time. "Give Squid A Break" just doesn't have the same appeal as swordfish.

One thing is evident, that knowledgeable fishermen with a broad view and a sense of responsibility toward the fisheries on which their way of life depends offer the most reasonable voices in the debate. Responsible men and women with a long history of involvement in commercial fishing may, in the long run, prove to be the best stewards of our fisheries. They need to be considered worth sustaining, too.

An article similar to this by the same author was printed by the New York Times.

|

What's a Red Herring?

by Mike Crowe

This article dealing with the herring fishery depicts a general overview of the industry. In later articles we will be taking a closer look at the different facets of the industry - the boats, the fishery and the canneries.

Herring may not be the star of the Maine fishing industry as is lobster (with its image appearing on everything from dinner plates to license plates), but it is none the less an important industry here. Not long ago the number of weirs, carriers and canneries along the coast attested to its much greater importance to many more people.  It is a fishery with a long and financially checkered history. Two of the more important roles it plays is supplying bait for Maine's premier fishery (lobster) and as a food source eaten around the world. It is a fishery with a long and financially checkered history. Two of the more important roles it plays is supplying bait for Maine's premier fishery (lobster) and as a food source eaten around the world.

As bait, herring makes the lobster fishing industry possible. Twenty years ago a good sized lobster boat would use 6 bushels of bait and today the same size boat uses 18-20 bushels. The lobster bait and the packed sardine industries developed commercially at about the same time. The market for sardines in the Bay of Fundy area began with the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. French fishermen had been catching sardines in the North Sea and selling them to canneries. Sardine brokers in New York were also marketing French sardines in America at that time. When the war cut off supplies, the New York brokers looked to the Passamaquoddy Bay area. After the Franco-Prussian War the French found that they had lost their American market to Maine packing plants.

Demand grew and by 1900 there were 79 canning plants in Maine, a great number of them in Eastport. Hundreds of boats and thousands of people were employed in the herring fishery. Eastport became known as "the sardine capitol of the world." Today there are 5 sardine canneries in Maine, and Maine is the only sardine producing state in the United States.

In the years of commercial herring fishing, weirs were used to catch them. There is evidence that weirs were used as early as 1850. Originally used by the Indians, the weir was built with poles driven into the mud of a bay. Brush was woven through these poles to create a barrier. This encirclement, from high water to below low water, formed a fence that trapped the fish once they entered. They were then seined and brought aboard by a dip net suspended by a boom.

Another method was stop seining or a shut-off. This method was more commonly used when herring regularly poured into bays and inlets, it is still used in a few areas along the coast. After fish have entered an inlet, a net is strung across from one side of the inlet to the other, trapping the fish.

At the turn of the century when weirs were common, the boats were known as carry away boats, later called sardine carriers. These small sail boats were also called pinkies. The capacity was about a dozen hogshead. (A hogshead is 17 1/2 bushels or 1225 lbs.) The carriers got larger over the years, until the last burst of construction in the 1940's produced boats with capacities of 100 hogsheads. By that time they were all power boats.

The fortunes of the industry rose and fell rapidly with the availability of fish and markets. World War I created the biggest boom. It generated an endless demand for canned goods high in protein. New canneries opened, old ones prospered and more fishermen built boats. A decade later the depression drove many out of business. World War II brought on another surge in demand for sardines and sardine boats that lasted into the 1950's.

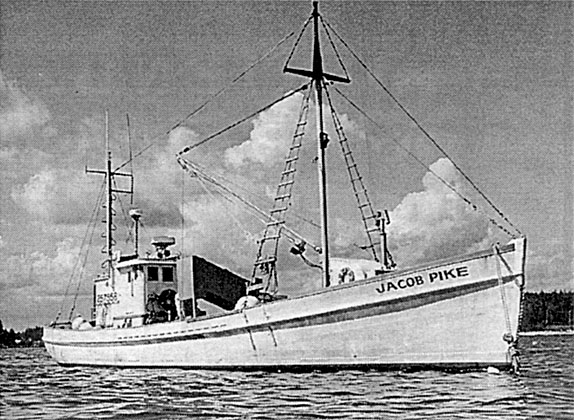

One of these boats was the Jacob Pike, built for Moses Pike, owner of Holmes Packing Company of Eastport. She was built in 1948 by the Newbert and Wallace Shipyard in Thomaston, Maine. This double ended carrier is 85' long and has a 17' beam, carries 100 hogsheads, is powered by a Detroit V1271, with a 54/40 4-bladed wheel and two generator sets. She is and has been highly regarded for her strength, seaworthiness and lines.

Sardine carrier builders along the coast built boats around steam bent timbers. The one exception was Newbert and Wallace. They used sawn timbers on all their carriers. The heavier 6"X6" timbers kept the boat from becoming limber. Steam bent timbered sardine boats were hard to keep from leaking. The Jacob Pike also has a 4"X10" clamp rather than hanging or lodging knees. It also had salt packed between the timbers, reducing rot above the water line.

Seiners would run the entire length of the Gulf of Maine. In the old days the sardine season ran from June to December, but now it is most of the year. Seiners arrive in the area where they intend to fish just before dark. They prepare to set a seine after dark when the herring rise from the deeper water. The seine is drawn around the herring and the bottom is closed by cinching a line that runs through metal rings. The herring are then pumped out and into the carrier hold. From the start of setting out the seine to the beginning of pumping about an hour passes. Pumping out the seine into the carrier and the seiner is done with the two boats about 15 feet apart. One set can fill the carrier, as well as the seiner.

When loaded, the Jacob Pike has about one foot of freeboard. The extra weight keeps her from being thrown around in rough weather, but does not keep her from getting up to 12 knots.

Today there is a demand for a higher quality product. To preserve the herring in the hold a "champagne system" is used that circulates icy salt water and air up through the load thereby keeping it chilled.

There is also an unusual byproduct of the herring. As the herring are pumped aboard, they are sent through screen-lined tumblers to remove the scales. This is not to make them more appealing to the lobsters but the scales are collected in baskets and sent off to be processed. In the 1930's a process was developed for extracting the pearlescent quality of the scales, only herring scales apparently. It is used to add a pearlescent appearance to soaps, automotive paints, shirt buttons, eye make-up, lipstick, etc. Would that make some lips red herrings?

With herring being largely fished off shore, it is difficult to realize that at one time it was as visible and prominent as lobster fishing is today.

|