|

Boatbuilding and fishing was what the Lowells did back in Jonesport since they arrived there from western Maine in the 1760’s. But it was the arrival of Will Frost on Beals Island off Jonesport, around 1912, that set the stage for change. Having grown up in Little River, Nova Scotia, Frost (1874-1967) was a third generation boatbuilder who first built a boat designed to carry power in 1904. Soon after, he was racing and regularly winning. Frost had been developing hull designs that would function more effectively with the recent introduction of the gasoline engine on sail boats.

Lightweight, high-compression engines were not available in the early years of Frost design work, so he concentrated on refining the efficiency of the bottom of the hull. Some modern hulls use big engines to get the boat up on the water where it can plane. Frost and Lowell boats cut and move through the water easily, swiftly and smoothly. William “Pappy” Frost was also known as the ‘Wizard of Beals,’ for reasons that are interesting today, but when most fishing boats still used sail power and the engine was very new, his abilities must have seemed like magic.

The genius of Frost’s work is widely-known and recognized. He is clearly one of, and possibly the most influential designer and builder in Maine history. He appeared at a critical time in boatbuilding history, when fishing boats were moving from sail power to engines. By the late ‘teens he had come a long way toward perfecting his powerboat hull.

It also happened to be a time when government bureaucracy was rearing it’s head for a little social engineering. Hull design was changing to accept the internal combustion engine, while the federal government, inadvertantly of course, would force the process to move along more quickly.

In 1919, radicals in the U.S. Congress passed the Volstead Act, which began the “Prohibition” era. After a few thousand years of being a part of social ritual for most cultures on earth, a few religious, social and politically- motivated individuals decided everyone else in the country would be better “folks” if they were not allowed to drink alcohol. For 14 years alcohol was the boogyman, the Salem witches and McCarthy’s commies all in one. It’s a curious thing how governments, including our own, can be taken over by crazies who subsequently run the country through the wringer.”

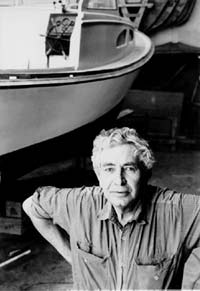

Carroll Lowell, 1992, in the shop at Even Keel Marine Specialties in Yarmouth. Carroll opened the business in 1961 and subsequently built hundreds of commercial and pleasure boats of his and brother Royal’s design. Carroll’s sons Jamie and Joe continue the family tradition there. |

Fortunately, the human spirit has eventually risen up to throw out these opportunistic yahoos. The human spirit rose immediately in response to Prohibition, and in coastal Maine, it rose in spades. In fact, for Maine, Prohibition was an economic opportunity, out of which came, among other things, the modern lobster boat.

By 1920, the already legendary Will Frost built hulls that performed better than most others powered by the gasoline engine. Frost’s flatter aft sections and “torpedo” stern were breaking new ground in the waters off Jonesport, Maine. When prohibition started and ships from Canada loaded with liquor anchored just beyond the three mile limit, fishermen, businessmen and the underemployed went out to bring the cargo ashore.

The government responded with near-shore seizures. People running the rum to shore took notice of Frosts’ fast boats and ordered them. Frost responded to demand with bigger engines and better boats. The Jonesport waters were his Salt Flats testing ground. At times, the only trace the feds left behind, were the faint thuds of their bullets impacting the back of the sand-packed double wall of the wheel house.

The government boats could not get near the Frost boats, and they began buying his boats. Frost, in fact, was building rumrunners at one end of his yard and similar boats for the Coast Guard at the other end of the yard. The cat-and-mouse game in the war on thirst was good business for some boatbuilders along the coast. It was also a new business for those displaced by the depression.

Frost is said to have built between 700 and 1,000 boats in his lifetime. In the 20 years he lived on Beals, many area men worked in his shop. His ideas became part of the boatbuilding culture there. His influence was very much a part of the development of the “Jonesporter,” a regional lobster boat style that was seaworthy-fast, low, sleek and good-looking.

In 1926, Willhelmina, Frost’s oldest daughter, married local boatbuilder and fisherman Riley Lowell. Riley labored alongside Frost all his working life. That year, Royal Lowell was born to them. He was followed by Daniel, Carroll, Donny and Malcom. The Depression began in 1929 and prohibition ended in 1933, and with it the rumrunner market. The same year the Frosts and the Lowells moved to Massachusetts, then Rhode Island, where Will established Frost & Company. They built in different locations and 14 years later the family was back in Maine building draggers in Portland.

Riley Lowell passed on his interest in boatbuilding to his five sons. They literally grew up on the shop floor with Riley and Will Frost, in a particularly intense version of an ages-old tradition of handing on the family’s assets in the form of knowledge and skills. Here were two experienced boatbuilding families working and living together, one among them arguably the inventor of the modern power boat hull and surely the father of the modern Maine lobster boat.

Royal and Carroll became highly-regarded designers. Their work continues to be built along the Maine coast and others. They continued to design the smooth sailing boats that sliced through the water with little effort and lots of speed that their grandfather had introduced. Carroll rebuilt one of his grandfather’s most famous fishing boats in 1969. Merganser, built in 1948 for Chebegue Island fishermen Bob and Henry Dyer, was a long, graceful boat that many consider Frost’s best boat, and some the best boat from that period. Later in life, Carroll focused on design, and one of the people who came to him for designs was the now noted builder Peter Kass.

Royal had always leaned toward design, and produced many boats, including the lobster boat racing favorite Red Baron. Carroll, Royal and Danny, together built many of the boats Carroll and Royal designed. Royal died in 1983, after having built hundreds of boats and creating hundreds of designs that continue to be built by the Lowells and others. The family’s history was important to Riley’s children, as it is important to Carroll’s sons — Jamie, Jesse and Joe. Jamie and Joe have run Even Keel Marine since Carroll’s death in 1997. Carroll’s sons have preserved and organized their unique family history and present part of it on their website, www.lowellbrothers.com. Families organized around an occupation were once more common. Families organized around a central figure the likes of the “Wizard of Beals” have always been rare.

One example of the Lowell’s sense of continuity was the completion of a boat started by their father in the 1980’s. The customer ordered the 40' boat on somewhat unusual terms. He had no formal plan for paying for it, had a somewhat mysterious background, no one seemed sure where he was from, and was not always around, though he lived in the Yarmouth area. Carroll still did business on a hand shake and started the project. He had to set it aside when no funds were available from the customer, started it on his own again, then put it aside again before he died in 1997. The customer had not shown up in 15 years when another customer expressed interest in the partially-built boat. Carroll’s sons, Jamie and Joe, decided to finish it for them. Twenty years after the keel was laid, the boat was launched and named the Carroll L by the new owners, after the then deceased designer.

Carroll was well aware of the unique family he grew up in, and reminisced about his youth in a 1986 article in Wooden Boat magazine:

“My grandfather would cut a model; the rest of the crew would be working, and he’d have it out there and take the drawshave to it, and he would say to me, ‘Now hold it!’ So I would bear down, and he would cut away on it, and hold it up, and maybe leave it and come back the next day. You couldn’t help but learn from watching him. In the old days, a man would have someone hold something for him; this is how we learned . . . For instance, I was on the loft floor when I was a kid — watching ‘em. Sometimes I didn’t understand, but after a while it would come to me.”

Will Frost was a master boatbuilder who knew well how all the parts of a wooden boat had to be made, sized and put together. He was also a skilled designer, with an exceptional eye for the lines of a boat. But, perhaps most of all, he was a naval engineering scientist, trained by himself and the generations of his family’s builders before him, creating the hulls for small boats that both enabled and maximized the transition from sail to power. What scientists may do in a testing tank laboratory at MIT, Frost was doing in his head. While the lab test results were read from a sheet of paper, Frosts results were seen passing by off the end of a wharf or felt beneath his feet when standing at the helm. This is the legacy that has come down to his greatgrandsons on the Cousins River in Yarmouth.

|