Endline End Game

Continued from December 2019 Homepage

At a Department of Marine Resources meeting Nov. 4 in Ellsworth, Rocky Alley, president of the Maine Lobstering Union and a Jonesport lobsterman, commented on what he called “bad science” underlying the perception that Maine’s lobster industry is a threat to the North Atlantic right whale. Laurie Schreiber photo

Other measures in the state plan call for weak links, gear-marking, and 100 percent harvester reporting.

The state plan, like the federal plan, is designed to protect the endangered North Atlantic right whale, said Keliher.

Maine’s lobster fishery, he said, has “a bullseye” on its back.

Soon after the presentations, the Maine Lobstermen’s Association (MLA) voted not to support the DMR whale plan “because it seeks reductions that exceed the documented risk posed by the Maine lobster fishery as demonstrated in MLA’s analysis” of National Marine Fishery Service (NMFS) data, MLA said in a press release.

“The MLA conducted a thorough analysis of fishing gear removed from entangled right whales which revealed that lobster is the least prevalent gear,” the release said. “The MLA is also concerned the state’s plan creates unresolved safety and operational challenges for some sectors of the lobster industry.”

“How many whales

have we killed?”

– lobsterman

“In the last decade,

directly, with Maine gear

on them? None.”

– Pat Keliher,

DMR Commissioner

The MLA called the state’s plan “a tremendous improvement” over the federal proposal presented in June. “The MLA will continue to provide constructive feedback to DMR and work with our members to draft a whale protection plan to address the varying risk to right whales across the Maine lobster fishery while minimizing the operational, safety and economic concerns identified by MLA’s members,” the release said. “MLA remains committed to playing its part in a comprehensive, effective whale conservation plan that enables right whales to recover and thrive.”

At the DMR’s meeting in Ellsworth on Nov. 4, Rocky Alley, president of the Maine Lobstering Union and a Jonesport lobsterman, noted that Canada’s fisheries are implicated in deaths and injuries of right whales, not Maine’s.

“We’ve seen bad science against lobster fishermen in the state of Maine,” Alley said. “When will they come up with new science that makes sense? How many whales have we killed?”

“In the last decade, directly, with Maine gear on them? None,” responded Keliher.

“Yet we’re regulated to death,” continued Alley. “Every four or five years they come out with new regulations. The next thing you know we’ll be cutting down on our traps. When in hell do the fishermen ever stand a chance?...It isn’t right. We’re getting pounded and pounded. We shouldn’t be the lowest-hanging fruit.”

Department of Marine Resources Commissioner Patrick Keliher presented a modified plan designed to reduce risk of fishing line entanglement to North Atlantic right whales, during a series of meetings in early November. Laurie Schreiber photo

The federal plan calls for halving the number of vertical lines used by the industry. That’s 5.5 million vertical lines overall. But most of Maine’s lobster fishing takes place in the nearshore exemption area, Keliher said.

The state plan would take over 4 million vertical lines off the table.

“Now we’re talking about a reduction from only about 1.4 million endlines,” he said.

The reduction of endlines outside of the exempted area would mean that fishermen would have to trawl up more traps to their endlines.

The state plan proposes:

• In the nearshore exemption area – status quo

• From the exemption line to three miles – a minimum of three traps per trawl

• Three to six miles from shore – a minimum of eight traps per trawl with two endlines, or 4 traps per trawl with one endline

• Six miles to 12 miles from shore – a minimum of 16 traps per trawl

• Beyond 12 miles – a minimum of 24 traps per trawl

With regard to weak links, the draft plan proposes:

• Inside three miles - one weak point integrated into each vertical line

• Outside three miles - two weak points, one in the middle of the line, and one that’s one-quarter of the way down from the buoy.

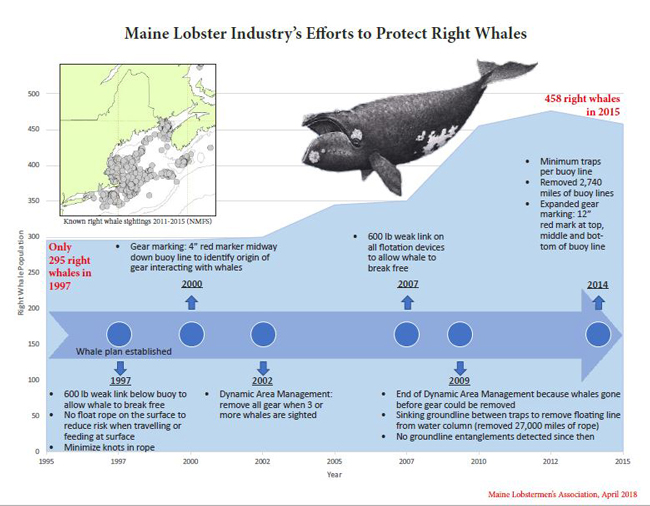

This graphic depicts the Maine lobster industry’s efforts to protect the North Atlantic right whale. Graphic courtesy MLA.

Studies have shown right whales can break free of line at or under 1,700 pounds of pressure. The DMR is conducting ongoing weak-link tests at its lab, Keliher said.

“I’m proposing that the DMR work with the industry in various areas of the state, different tides and water depths, and make sure you guys can handle this from a safety standpoint,” he said. “I’m going to push back against the feds if it becomes a safety issue.”

A Maine-only gear marking plan is expected to provide targeted data for researchers trying the determine the origin of gear involved in an entanglement. It will allow researchers to differentiate gear found on entangled whales from Maine gear.

Provisions of the plan include:

• Red marks on vertical lines, on both state and federally permitted Maine vessels, would be replaced by Maine-specific purple marks.

• A 36-inch purple mark in the top two fathom of the line

• Outside exempt waters, harvesters would be required to add an additional green mark to vertical lines

“I’m going to push back

against the feds if it

becomes

a safety issue.”

– Pat Keliher

“It’s important to differentiate the exempted waters because we’re making the case that there are no whales in the exempted waters,” said Keliher. “We want a true separation.”

The goal is to implement Maine-specific gear marks by June 1, 2020.

“So you have between now and then to deal with gear markings,” Keliher told fishermen. “People say, ‘Can I just leave my red mark on and then mark with purple?’ You could. But I recommend you don’t. You need to understand that if you leave the red mark on, there are implications to other areas that have red marks. The idea is to be set apart from everyone else.”

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission mandates 100 percent harvester reporting by Jan. 1 , 2024, he said.

“We’re trying to fast-track that because it’s beneficial,” he said. “But if we can’t cover the costs, we can’t implement it early.”

All licensed Maine lobster harvesters would be required to provide monthly reports, to include information on fishing location and effort. The timing of the implementation would depend on funding from other sources.

“My goal is not to put the expense on the industry,” Keliher said. The reporting system would be based on cell-based service such as cellphones and tablets.

“These are things coming down from the federal government, so my goal is to get as much federal funding as we can,” Keliher said. “To make this work, there’s an educational component. Not everyone will have a tablet or smartphone, so we’ll have to work through that with additional reporting on paper.”

The state’s goal is to implement 100% harvester reporting by 2021, he added.

Reporting requirements could have ancillary benefits as conversations continue around other offshore uses, such as wind energy and habitat, Keliher said.

Keliher said the DMR’s plan was based on comments from the industry, which largely said the federal plan’s trawling up scenarios would not work for large portions of the fishery, inshore and offshore; that it posed major safety concerns, and that it would result in additional rope in the water.

The key element in the DMR’s draft plan, he said, is addressing risk where it’s greatest.

“The risk of entanglement in exempted areas is very low,” he said.

The goal is to implement

Maine-specific gear marks

by June 1, 2020.

The state plan also asks the federal government for flexibility, from a zone perspective and from an individual perspective, for safety considerations.

“We’ll ask for flexibility to address conservation equivalency at the zone level and mechanisms to address individual safety concerns,” Keliher said. “The zone councils already have the authority to set trap limits, maximum trawl lengths, and exit ratios.”

The DMR plan does not include closures and trap reductions.

“We’ve worked to avoid trap reductions,” he said. “It’s my belief trap reductions should be a conversation that pertains to lobster biology and not whale biology.”

Stonington fisherman Julie Eaton said she supported gear marking.

“That’s urgently needed,” Eaton said. “We’re guilty until we’re proven innocent by NOAA on this issue. So let’s clear our name and move on. Once we can clear our name, we’ll be better off for it.”

“I’m a big proponent of marking gear as soon as possible,” agreed another fisherman. “These marks are important. They’ll be a pain in the rump for people, but it’s data we need.”

Other supported gear-marking as well, but said they needed a longer period of time to implement it.

“Whenever we’ve had to do implementations before, we’ve had a little more room to work than June 1, 2020,” said Zone B fisherman Jon Carter. “That’s going to be quite a stretch, for people to work on their gear and put all these markings in their gear, especially guys who fish all winter. Has there been a any talk about talking to rope manufacturers and saying, Hey, if you’re going to manufacture rope for the state of Maine, let’s require you to put purple tracer in the rope? That would b a simple fix right there.”

Jack Merrill, a Cranberry Isles fisherman, agreed the June 2020 deadline was too tight.

“For me, and a lot of guys who fish all winter, I just can’t do that,” Merrill said.

Adding weak links to ropes and trawling up doesn’t make sense, he continued. It would cause many fishermen to move their gear inshore.

“Their boats aren’t big enough,” he said. “They’re not geared up to trawl up, so you change the dynamics of the fishery and put a lot of people into a really bad spot.”

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission

mandates 100 percent

harvester reporting

by

Jan. 1, 2024.

Merrill added, “The whole thing’s ridiculous….We care about the whales as much as anybody on this planet. We care about all wildlife. We’re with nature every day. It’s important to us. But I think we’re being really unfairly treated in this situation.”

Another fisherman wanted to know how fishermen could be expected to put more traps on an endline and also weaken the line.

“We’ll be parting gear all the time,” he said. “It can’t work…You’ve got to just say, ‘We can’t do this. It’s not going to work.’ ”

“I get it,” responded Keliher. “But if you say, ‘It just won’t work,’ they’re going to force something else on you to take even more gear out of the water….I’m sure they’ll love to hear that you can’t do it, because it pushes the conversation to ropeless gear. So we need to find something that will work. That’s why I’m committed to working with the industry on gear configurations or anything else we can do before these whale rules are finalized.”

Kristan Porter, who said he was speaking for himself and not as president of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association, said he was going to work with different configurations of weak links to try to make them work.

“I fish in the some of the harshest conditions,” said Porter. “But I’m going to try different scenarios….The reason I’m going to try it is, we’re getting a pretty good chunk of risk reduction by going this route. If we say it won’t work and throw it out, we’re going to have to cut somewhere else….I encourage people to try to do this because we’ll get some bang for the buck.”

One fisherman wanted to know if latent effort is complicating the situation, by making it appear there are more endlines in the water than there really are.

“We need to have a conversation about latency and how it hurts us immediately and in the long-term,” responded Keliher. “We hear constantly at meetings from the federal agency or from individuals representing different environmental groups about Maine’s three million trap tags. It doesn’t matter that we tell them those three million trap tags aren’t being fished. They want to use them against us. Harvester reporting starts to get us there, but it doesn’t get there all the way.”

Another fisherman wanted to know what the end game was.

“We’re looking at a 60 percent reduction” of risk to the North Atlantic right whale, he said. “Are we going to be doing this every five years?...We have no entanglement, no deaths. We have the science on our side. But this plan isn’t going to save a single whale. It’s going to cause serious injury to fishermen.”

“This is Maine’s line in the sand,” responded Keliher. Still, he continued, “We know, based on acoustical data and based on sighting data, that the farther offshore you get, the greater the chance you meet a right whale….They don’t levitate between Massachusetts Bay and Canada.”

Keliher said the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) will consider the state’s plan. It’s expected NOAA will issue a final rule in the summer of 2020, with an implementation date likely in 2021, he said.

“The wild card remains the court system,” added Keliher. “There are still several court cases that are outstanding.”