Lobstermen Snarled in Endline Impasse

Continued from July 2019 Homepage

“The whole thing is

complicated but, at the

end of the day, we have

to have a conversation

about all these pieces.”

– Robin Hadlock Seely

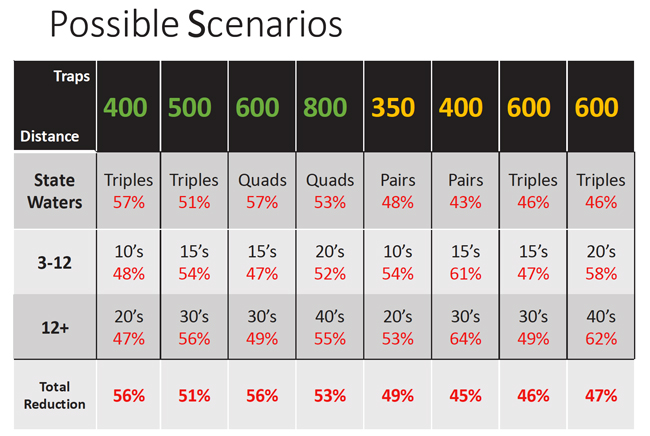

Approximately 30 scenarios, so far, are based on various configurations of reduced trap numbers and increased trawling-up. Each scenario would potentially achieve a certain percentage reduction of risk to the right whale.

For example, if the maximum number of traps remains 800, but fishermen fish four traps per endline in state waters, there would be a 53% reduction of risk.

The measures put forward by the TRT are driven by the Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

“The whole thing is complicated but, at the end of the day, we have to have a conversation about all these pieces,” said Keliher.

“Not all the scenarios made it to 50%,” said Carl Wilson, director of the DMR’s bureau of marine science. “The tool box is pretty empty on how we can get there.”

The DMR is also looking at what areas of Maine and what time of year the risk is greatest, said Wilson. For example, he said, right whales have been spotted north of Mount Desert Rock.

“That’s considered a risky area by some, so that was given a different weight,” he said.

This graphic shows possible scenarios for the amount of risk reduction that would be achieved by reductions

This graphic shows possible scenarios for the amount of risk reduction that would be achieved by reductions

of trap and endline numbers. Courtesy of Department of Marine Resources.

Other measures under consideration include vessel tracking in federal waters, 100 percent reporting by harvesters, and gear marking. Those measures are designed to better identify where entangling gear originated and where lobster gear and right whales intersect. Maine currently has a 10 percent harvester reporting requirement.

“We’re trying to figure out how to do that for 2021,” he said. “Not having that information makes it difficult” to negotiate.

The DMR is calling for a quarter-mile exemption zone from any measures in inshore shallow waters, Keliher said. That would help maintain fleet diversity by allowing smaller boats and children who have student licenses to continue to fish as they have been, he said.

The TRT is also

considering Maine-specific

gear marking.

Given the expected strictures on the fishery, the industry will likely also look into new licensing reductions, Keliher said. However, he added, the DMR will continue to support diversity in the fishery. Diversity includes types of boats, from inshore skiffs to big offshore boats; the ability of fishing family offspring and apprentices to enter the fishery; and different fishing practices through the region.

Part of the problem is that the distribution and habitat use of right whales in the Gulf of Maine is shifting, said Erin Summers, with DMR’s protected resources division.

“There are a lot of unknowns in the question of where are they at any given time,” Summers said.

Commenters pointed out that new measures will likely cause changes in fishing practices, which will then have to go under review again. For example, one said, fishermen who typically frequent federal waters, who are required to trawl up a higher number of traps, might decide to move into state waters instead to take advantage of the lower trawl-up numbers, thus increasing the number of vertical lines overall.

Federal regulators “realize that whatever we do, everything will change,” responded Keliher. “And they’ll look at it again. If we have to make adjustments, it’s easier to do it through the zone process and regulatory action rather than though the federal agency. All of these scenarios will cause some segment of the industry to change how they’re going to fish.”

Implementation of new regulations could occur in 2021. However, said Keliher, with three lawsuits ongoing in the matter, a court could intervene and tell NMFS that implementation of new rules needs to be accomplished sooner, he said.

Approximately 30 scenarios

are based on reduced trap

numbers and increased

trawling-up.

The foundation of the TRT consensus agreement is that each jurisdiction overseeing the lobster fishery needs to meet a 60 percent risk reduction, he said. Jurisdictions outside of Maine are looking at different suites of measures, he noted.

Maine achieved a couple of victories during the TRT discussions, he said. One was taking ropeless fishing off the table.

“Ropeless fishing was a serious consideration by many of the people around that table,” he said. “We were able to get that off the table.”

The other was getting closures of fishing areas off the table. The TRT had been looking at an area around Mount Desert Rock and other areas during peak fishing time, he said. The concept of area closures remains in play if it’s something the zones want to talk about, he noted, but added, “I want to stress that, once you have a closed area, it’s a closed area.”

Maine’s goal is a 50 percent reduction in the number of endlines, along with a 10 percent risk reduction by ensuring “toppers” in federal waters have a breaking strength of 1,700 pounds.

The TRT is also considering Maine-specific gear marking.

“It would be a benefit to know if it’s your rope or not your rope,” Keliher said.

We’re under a tight

timeline to finish

the proposed rule by

the end of this year.

– Michael Asaro, PhD,

Large whale biologist,

NOAA

Wilson noted that Massachusetts has decided to use “South Shore” sleeves in its toppers to achieve the 1,700-pound breaking strength target. The sleeve is a connector between two segments of vertical line.

For Maine, Wilson said, “All creative ideas are on the table.”

“Is there a time of year when right whales are considered not to be here?” Zone B Council Chair David Horner asked. “Is there a time of year when we could not do this?”

“There’s never been a right whale entangled here,” said another council member. “So how can they say 12 months a year there’s a possibility they’ll be here?”

Keliher said the federal approach is to look at the risk of the total amount of endlines.

“It would be a true statement that in areas in the Gulf of Maine the risk would be extremely low,” he said. “But the federal agency will say the risk will never totally go away.”

Keliher said the state has informed federal regulators that Maine will tackle the issue zone by zone.

“We knew from the zone perspective that we had to recognize different fishing practices,” he said. “They realize that’s the best approach for the state, because we’re so much bigger than all the rest of the jurisdictions.”

Keliher asked the councils

to discuss the issues

with their districts

and run scenarios.

Keliher continued, “they will have an issue if we don’t’ achieve the 60 percent statewide. When we do this again in August, we’ll have to look zone by zone at how things look.”

A council member wanted to know if latent licenses have been figured into the calculations.

Keliher agreed latent license are part of the discussion.

“If you have to come down and someone else is building up, how does that work?” he said. As part of the conversation, he said, the zones have to talk about possibly creating a tiered license system.

“If we consider the amount of vertical lines we get rid of, what does that say about licenses in the future?” one commenter asked. “You’d have to also cap the amount of tags we have so there’s never another vertical line set.”

“I expect every zone will start a conversation about ratios,” responded Keliher. “There are already conversations about waiting lists and student licenses.”

State Rep. Billy Bob Faulkingham suggested capping the number of endlines versus capping the number of traps.

est of the jurisdictions.”The distribution and

habitat use of right whales

in the Gulf of Maine

is shifting.

– Erin Summers,

Maine DMR

“That’s something we’ve talked about internally,” responded Keliher. “It’s something that can be considered.”

Keliher asked the councils to discuss the issues with their districts and run scenarios. He offered the DMR’s assistance in running the numbers. The DMR plans to have a second round of meetings with the zones in August.

One of the ideas bounced around is setting a statewide baseline regulation, then letting individual zones determine numbers of traps and endlines, or conservation equivalencies, that would meet the reduction goal, Keliher said.

“I want the industry to help decide,” he said.

One commenter wanted to know if the industry could file its own lawsuit on the matter.

“It would be filed by the state of Maine,” said Keliher. However, he added, “If we thought we could just say, ‘No, you can’t do this, and whatever you’re going do, we’re going to file a lawsuit,’ we would have done it a long time ago.”

However, he added, “everything the DMR does now is building a record, if a lawsuit is filed.”

One commenter wanted to know if tagging the whales would be helpful, so fishermen could keep tabs on where they are. Keliher said that would be problematic because the whale’s anatomy doesn’t hold tags and the tagged area tends to become infected.

At the New England Fishery Management Council’s June 13 meeting in Portland, Michael Asaro, a marine mammal program coordinator with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), said NMFS will hold scoping meetings in New England this summer to get input on the TRT proposals.

“We’re under a tight timeline to finish the proposed rule by the end of this year,” Asaro said.

The DMR is scheduled to submit its proposal to NMFS in September. The schedule calls for NMFS to publish its proposed rule and seek public comment on the proposal sometime this coming winter.