When the Civil War Came to Maine

by Tom Seymour

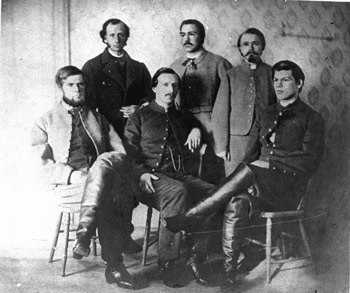

A Feb. 15, 1864 photo showing five of the at least 18 St. Albans Raiders following their escape to Canada and while they were held for trial in Montreal. The youthful Confederate Lt. Bennett Young (right), was the small band’s leader. Young took charge of the mission almost right from the start, recruiting other Confederates who, like himself, had escaped from Union prisons and found their way into Canada.

Mention Maine during America’s Civil War and thoughts of Joshua Chamberlain and the 20th Maine at Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg come immediately to mind.

Some few may recall that Maine had training forts for troops bound for the southern front. Paramount among these was Fort Knox on the Penobscot Narrows section of Penobscot River between the towns of Prospect and Bucksport.

But Fort Knox never saw action, never fired a gun in anger.

However, Maine did see real Civil War battles, only not among ground forces. The action occurred at sea, when Confederate raiders not only harassed Maine’s shipping, but also stole a Coast Guard cutter in Portland. Also, a Confederate vessel pursued a failed attack on a Maine fort. Top all this off with a bank raid by Confederates upon a Washington County, Maine, bank and we have some interesting, Maine Civil War action.

C.S.S. Tallahassee

The Confederate raider, C.S.S. Tallahassee, a former blockade runner built on the River Thames in England, broke through the Federal blockade on August 6, 1864 and proceeded on a campaign of destruction to northern shipping. Tallahassee captured 33 vessels, destroying 26 of them. The seven vessels that were not totally destroyed were either released or bonded.

Among her conquests the Tallahassee captured eight Maine vessels, plus one vessel of unknown origin with a ship’s master from Maine, on way to New York. Here is a list of those vessels.

• Schooner Carroll of East Machias, Maine, Bonded for the sum of $10,000 and released.

• Bark Glenavon, of Thomaston, Maine, scuttled.

• Ship James Littlefield, Bangor, Maine, scuttled.

• Schooner Atlantic, Addison, Maine, burned.

• Schooner Robert E. Packer, Bath, Maine, burned.

• Bark P.C. Alexander. Harpswell, Maine, burned.

• Brig Neva, East Machias, Maine, bonded for $17,500 and filled with previously captured prisoners.

• Schooner Spokane, origin unknown, master from Calais, Maine. Burned.

Besides the monetary loss to Maine shipping interests, Tallahassee’s raids had a more far-reaching effect. Cities and towns up and down the Maine coast were, and rightfully so, put on constant alert, never knowing when and if Tallahassee or another Confederate raider would show up on their doorsteps. Maine was up in arms and as a consequence, forts and batteries sprang up nearly overnight in order to fend off any further Confederate depredations or attacks.

Battle of Portland Harbor

A bigger catalyst than the reign of terror by the Tallahassee, the Battle of Portland Harbor set Mainers on edge like nothing else could have. Newspapers, seizing upon the opportunity to grab headlines that would be read around the world, likewise contributed to the bedlam.

On June 24, 1863, Confederate raider Tacony attempted to escape capture from the pursuing United States Navy, captured a Maine fishing vessel out of Southport named Archer. After boarding Archer and transferring crew and cargo to that vessel, the Confederates burned Tacony and sped away, hoping that the Federal Navy would think that Tacony and crew were destroyed.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, said sketches of “the principal street of St. Albans” were based on a photograph by T.G. Richardson. Richardson, an early professional photographer in St. Albans, was among the local citizens rounded up and held on the town green during the bank robberies. Lt. Bennett Young stood outside the American House hotel on Main Street just after 3 p.m. shouting his intention to take the town “in the name of the Confederate States of America.” This scene of some of the raiders forcing townspeople into the park, took place in front of the American House. While this happened, other raiders began robbing the three banks. The St. Albans Academy is seen in this illustration at the center in back of the park. School children and their teacher were watching as the raid played out. About 12 local citizens were hustled into the park. One of them suffered a bullet wound when he had refused to cooperate.

Two days later a small party from Archer entered Portland Harbor, disguised as fishermen. After reconnoitering the area, the raiders proceeded to the Federal Wharf and seized U. S. Revenue Cutter Caleb Cushing. This was the perfect vessel to make their escape, since its boilers were hot, allowing them to turn up steam and quickly head out to sea.

The army garrison of Fort Preble in nearby South Portland was soon alerted to the theft of United States property at the hands of Confederates. Accordingly, thirty soldiers from Fort Preble, accompanied by 100 civilian volunteers, along with two artillery pieces from the fort, were sent aboard the commandeered steamer Forest City and the sidewheeler Chesapeake.

The two vessels steamed off in pursuit of the Cushing. A battle ensued and the Confederates finally surrendered. But before leaving ship, the rebel raiders set fire to the Cushing. As fire spread, it finally reached the ships powder and ammunition stores and the Cushing exploded in a ball of fire, the concussion from the explosion rattling windows in Portland. It was heard for miles around.

Coastal Defenses

While the threat of continued Confederate raids along the Maine coast was very real, hyped newspaper reports of the battle set emotions aflame. In only a short time, Maine coastal towns and cities began building forts and batteries in order to meet the potential Confederate challenges. Also, older, existing forts were refitted and garrisoned for the duration of the war.

The following list of forts or batteries that were built as a response to the Confederate threat and those that were rebuilt and/or re-garrisoned gives a good, though possibly incomplete, idea of how seriously Maine communities took the threat of Confederate attacks from the sea.

First, here are fortifications that were newly built and garrisoned to respond to Confederate attack. These are:

• Fort Machias, Machiasport, a 5-gun earthenware fort, built near existing Fort O’Brien, 1863-1865.

• Belfast Batteries, two batteries built opposite each other on east and west entrances to Belfast Harbor, 1863-1865.

• Rockland Batteries – One battery built on current site of Samoset Resort in Rockland and another battery slightly south of that at Owls Head.

Next, here are some forts that were rebuilt, expanded and re-garrisoned:

• Fort Madison, Castine, rebuilt and expanded, renamed Fort United States, 1863-1865.

• Fort Knox, Prospect, Garrisoned during Civil War, also training camp for troops headed to the field.

• Fort Edgecomb, Edgecomb, re-armed and garrisoned in 1864 after Confederate raider Tallahassee spotted offshore.

Bank Raids

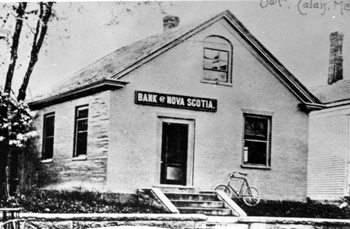

Formerly the Calais Bank during the Civil War when Confederates attempted to rob it in 1864. Four Confederates crossed over to Calais from St. Stephen and attempted to rob the Calais Bank. News of the raid had leaked out beforehand. The Rebels walked into a trap and were captured. Each was armed with a revolver and a dirk. The leader, Captain William Collins, carried a Confederate flag. Calais Advertiser, 21 July 1864.

In addition to attacking Maine’s shipping and her coastal defenses, Confederate raiders, hiding in neutral Canada, planned and executed raids on banks in Calais, Maine. Another rebel raid occurred in nearby St. Albans, Vermont.

The Calais raid was the brainchild of one William Collins, a Confederate agent residing in the town of St. John, New Brunswick, Canada. Collins had plans to take up to 30 picked men and attack Calais, Maine, first robbing the bank and then burning the town.

While this was not in any way a major Confederate offensive, Collins hoped that it would help the Confederate cause by first, using the stolen money to help the Confederacy and second and more important, to divert Federal troops from the war in the south to protect northern state’s interests.

Also, it was hoped, and it turned out to be a vain hope, that seeing unrest in the North due to the continuing war, foreign nations, particularly England, may finally recognize the Confederacy as a legitimate nation.

Collins and his friends may have succeeded, but American Counsel James Howard, having been warned of the impending raid by John Collins, William’s brother, informed the people of Calais of their precarious situation.

While Calais had only two hours lead time to prepare for the raid, that was enough to set a trap for the Confederate raiders. Part of a company of State’s Guards was able to place themselves in order to apprehend the Confederates.

When the raiders finally approached Calais in a small rowboat on Monday, July 18, 1864, there were only three others besides Collins. The rest sensed danger and backed out at the last moment.

As Collins and associates entered the Calais Bank, their robbery attempt was cut short when Guards ran into the bank and grabbed them. Once captured, Collins announced that the rolled-up Confederate banner had flown over Calais, Maine prior to the robbery.

So not only did armed Confederates attempt to rob the Calais Bank, a Confederate banner had, ever-so-briefly, flown over this Maine town, a first for the Civil War.

As a postscript, Confederate raiders hit three different banks in St. Albans, Vermont, on October 19, 1864. wounding a number of civilians, one mortally. Afterward the raiders, led by Lt. Bennett H. Young of the Confederate States of America, fled to safety across the Vermont-Quebec border, bringing to a close the final act of Confederate armed raids in Maine and Northern New England. In another century, a movie, “The Raid,” – 1954, would be made about this famous raid.

For further infomation visit The St. Albans Raid website.