B O O K R E V I E W

Between A Rock and A Better Place

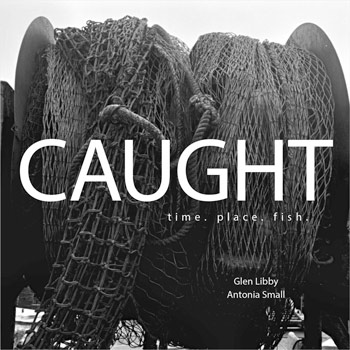

Caught

time. place. fish.

Glen Libby & Antonia Small

Wrack Line Books

116 pages

$40.00

New science from a joint New England Fishery Management Council (NEFMC) and Canadian effort has delivered findings in its summary that appear to be the latest fisheries management conflicting data conundrum.

A few generations of New England ground fishermen have slogged through similar management decrees. All the while, small boat fishermen have been driven out of business. The economies of these communities have for generations depended on fishing and are now being driven to the edge of survival.

Glen Libby, a lifelong fisherman, former NEFMC member and now community business activist, has written in Caught what may be the clearest, most concise, and understandable explanation of how New England ground fishing over the last 50 years has fallen to where it is today. It is so clear and direct that it should be required reading for the New England Fishery Management Council.

Libby has fished out of Port Clyde since the 1970s. Caught is not so much about the decline of fishing in the Gulf of Maine as it is about what some individuals did to adapt to an unfolding reality in their ancestral home, economy and environment.

Port Clyde waterfront.

Caught tells the story of one fishing community’s response to being driven to the edge of the abyss by forces they were made to believe were beyond their control. Antonia Small’s photographs illustrate the story of a community all but surrounded by the sea. The photographs are unvarnished realism of community immersed in the distinct culture, history, place and self-reliance that is making a living from the sea. Libby notes that the federal management plan—whose authority descends from Congress, then to the Department of Commerce, to NOAA, and to NEFMC—was to consolidate the fleet (fewer but larger vessels). The Port Clyde plan was to flip the fed plan over and have a lot of small boats fishing from many ports.

Libby had fished for nearly 50 years when he decided to create something that could change the image and thereby the value of the fish his community landed. He observed that more small boats catching and selling a higher-value product through their own market network could be the antidote to the fleet consolidation driving the race to the bottom on the price of fish.

The community witnessed the decline of groundfish stocks, the consolidation of ownership of fishing permits and fish quota and the winter shrimp fishery move north of the GOM. He also saw these as threats to the foundation of his and other fishing communities all along the Maine coast. Fifty years in fishing, fisheries management council membership, engagement with scientists and hundreds of other fishermen can deliver a solid understanding of the groundfish industry. This also made Libby aware of the near-impenetrable top-down barriers to implementing real changes in fisheries management policy.

FV Skipper.

“Having nothing left to lose can be frightening or liberating, or both; it depends on what you do next,” writes Libby. What he could do was change what was right in front of him. Getting more fish in the water was not going to happen soon enough. But changing the perception and the image of the fish that were caught was possible. Enlarging the base that local fishing businesses relied on by enabling them to benefit from transactions beyond the boat was possible. Processing, marketing and selling a higher-quality and higher-value product would create more jobs and keep more money in the community.

That was the seed idea, the beginning. What followed was convincing others that this could work and then just doing it. Caught is about the long, laborious and stressful learning curve in establishing Port Clyde Fresh Catch, the first Community Supported Fishery (CSF) in the U.S. and possibly the world.

“Learning is, possibly, the only wealth that there is. Attach a desire to effect change that contributes to the greater good by creating a new reality that is both good economically and sustainable and you now have a mission,” writes Libby. A chapter on the discovery of added value in crabmeat goes into lengthy detail. But the detail is presented to describe the required determination, attention to detail, thinking and the collective learning process that eventually produced a high-value, high-volume product for the fledgling enterprise.

Father and son mending nets.

The book is also about more than a community regrouping for a business plan. It is about the restoration of a community and the revival of a resourcefulness that original settlers needed to survive at the narrow edge of a wide sea.

Libby’s on-the-mark observations and comments alone are worth the read. He assessed the circumstances he faced and proceeded to change them from an informed and inspired position. “Changing the world was not as simple as it seemed here in Port Clyde, but a remarkable thing happened. Fishing communities all around the country became interested in replicating the model,” Libby writes.

Caught is not a “how to” on establishing a CSF, but it is a “what to realize” regarding individual and community determination, experimentation and blind faith.