Warming Water Changing Lobster Behavior

continued from May 2017 Homepage

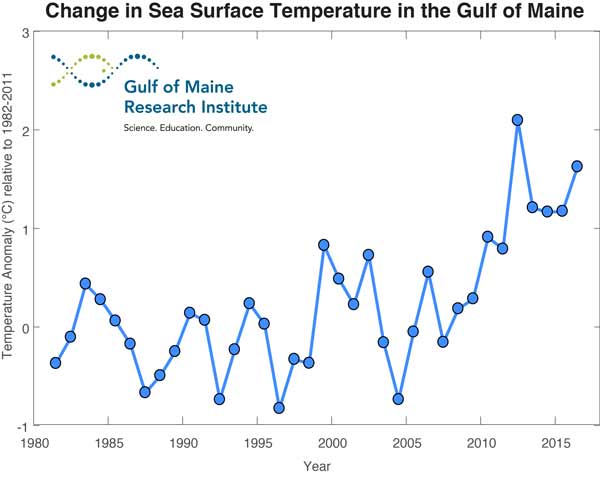

According to information on the NEFSC website, the eMOLT project is devoted to monitoring the physical environment of the Gulf of Maine and the Southern New England shelf, beginning in 2001. The devices measure bottom temperature, salinity, and current velocity, generating millions of hourly records of temperature, and thousands of hourly records of salinity and satellite drifter fixes. The latter uses GPS drifters that have logged hundreds of thousands of kilometers of ocean. Sensor data is wirelessly transmitted to a shipboard system as the drifters are hauled on deck. The project is conducted from New Jersey to Grand Manan, said Thompson. Taken together, the data show a general warming trend in the Gulf of Maine, she said.

GOMRI graphic

Maine and Canadian lobster fishermen said their observations confirm that finding.

“We believe that lobsters are settling much, much deeper, because nobody’s fishing the shoaler water like they used to anymore,” said Bar Harbor fisherman Jon Carter. In the past, he said, he and other fishermen typically fished in 10 fathoms, or 60 feet of water. But the lobsters have moved to 25 fathoms or more, even going to the cooler waters at 100 fathoms, he said.

Lawrence Cook, from Grand Manan, said he and others there are seeing berried lobsters much earlier in the year. Berried lobsters used to show up mid- to late-June. Now, berried lobsters are showing up in May, April, and some even in March, Cook said. He asked if it’s possible that lobsters are instinctively releasing eggs earlier in order to avoid releasing into summer’s warming waters.

“Are they trying to adjust naturally for what’s going on?” he asked.

Another fisherman, from Prince Edward Island, said another unusual occurrence is that lobsters are shedding in the spring, and there are two molts per season.

Bruce Fernald, from Islesford, said he and others are seeing unusually small egged lobsters.

Other research has been conducted on movement and connectivity of lobster populations in Canadian waters.

Brady Quinn, a biologist with the University of New Brunswick, said the research relates to how the fishery is managed, which is by zones in Maine and by lobster fishing areas (LFAs) in Canada.

“Often, with lobster, we fish out of certain areas, and the fishery is managed spatially,” Quinn said. “We’re interested in the movement within fishery areas. This has an important potential role in recruitment. It affects the influx of new individuals. This can affect fishery assessments, management, and the effectiveness of conservation efforts.”

For example, he said, if one management area receives a big portion of its new lobsters from another management area, due to lobster movement, then the areas shouldn’t be managed in isolation.

Lobsters have life cycles with two different components, Quinn said. There’s the benthic stage, when juveniles and adults live on the sea bottom. The larval stage inhabits the water column and surface of the ocean.

“Connectivity can occur at these two stages in different ways and maybe with different consequences,” he said.

In terms of the adult stages, lobsters can potentially walk around, move across fishery boundaries, and connect different areas, he said. The larval stage can swim or move with the currents. Methods have been devised to estimate connectivity and track where individuals go, he said. That mainly includes tagging adults and even juveniles. Sophisticated popup satellite tags, placed on a lobster, records physical data such as depth, temperature, and estimated location. After a year, the tags pop up to the surface and can be collected.

Larvae, are too tiny to tag or track, he said. Instead, he said, scientists use computer models of larval drift.

“You try to simulate the physical ocean with complicated computer programs, estimate different locations and times, based on physics and observation,” Quinn said. Other methods include genetic testing, since DNA, maternity or paternity, can give an estimate of whether individuals are interbreeding or are living in isolated populations.

The study of lobster movement is not new, he said. One well-known study was performed in the Bay of Fundy in 1980s. Lobsters were tagged and released in different locations; when they were later recaptured, scientists were able to note their movement patterns and rate of travel. One example, in New Brunswick, showed a lobster moved 790 kilometers, the longest distance recorded.

Despite the studies, said Quinn, “We don’t know a lot yet about the exact nature or importance of this kind of movement.”