BOEM, Fisheries and Wind

Learning to live together?

by Laurie Schreiber

PORTSMOUTH, NH—The fishing industry and the offshore wind energy industry are in the process of figuring out how to balance a relationship in areas where the two overlap, with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) acting as a mediator.

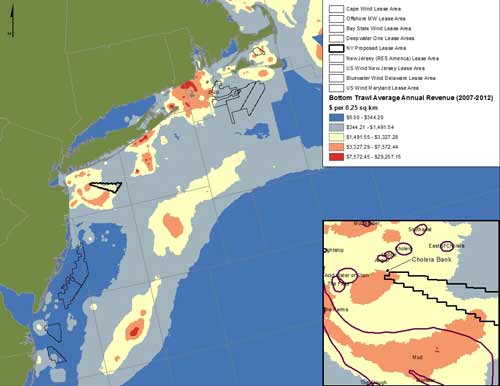

At its January meeting, BOEM biologist Brian Hooker told the New England Fishery Management Council (NEFMC) that total fishery revenue exposure in the New York Wind Energy Area leased by high-bidder Statoil is about $3.75 million. That breaks down to around $3 million for Atlantic sea scallop, just under $500,000 for all trawl gear, and under $250,000 for the mackerel, squid and butterfish fishery. Figures are based on average annual revenue from 2007-2012.

The figures represent an approximately 7 percent reduction in fisheries exposure due to the removal of 1,780 acres from lease consideration during the area’s latest environmental assessment.

New BOEM rules require wind area lessee’s to hire a fishery liaison and develop a fisheries communication plan.

With a bid of $42 million, Statoil Wind U.S. was declared the provisional bid winner in December 2016, when BOEM auctioned the area.

“This is the highest auction value we’ve received for any renewable energy auction to date,” Hooker said.

Statoil’s next step is a site assessment for eventual design of an offshore wind facility. The assessment must be conducted during a five-year term that ends February 2023.

The assessment will lead to Statoil’s proposal for a construction and operations plan, which will begin a 25-year period of operation that lasts until February 2042.

The New York wind energy lease is seen in the black outline off Long Island.

Image courtesy of Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

BOEM’s ongoing studies include:

• Socioeconomic impact of outer continteeal sheflllf wind energy development on fishing in the U.S. Atlantic.

• Electromagnetic field impacts on elasmobranches – sharks, rays and skates – and on American lobster movement and migration.

• Fishery physical habitat and benthic invertebrate baseline data collections.

• Fish telemetry in the mid-Atlantic.

In the meantime, BOEM has published guidelines to developers on:

• Preconstruction benthic habitat surveys

• Preconstruction fisheries surveys

• Communication with commercial and recreational fishermen.

Future fishery studies include:

• Understanding fish auditory thresholds/masking

• Southern New England lobster seasonal movement

• Real-time Opportunity for Development Environmental Observation, a program that uses acoustic environment monitoring and benthic habitat monitoring

NEFMC member Mark Gibson said he thought the fishing revenues might have been underestimated. He suggested that limited data sets were used in making the calculations regarding areas fished and the revenues coming out of those areas, and that vessel trip reports (VTR) don’t provide a fine-enough scale to provide the data needed.

Hooker said BOEM is looking into methodology that might provide a more detailed look. He said it’s difficult with the small spatial scales involved to understand just how to allocate for a trip that crosses a wind energy area, and to parse the math based on whether the entire trip is counted or just the part of the trip that occurs in the WEA.

“How that allocation works in the math is where a lot of discrepancy occurs,” he said.

With regard to the scallop fishery, NEFMC member Mary Beth Tooley noted the fishery occurs from Virginia to the Hague Line, encompassing a large area.

“So it doesn’t surprise me to see the percentage, but looking at it that way doesn’t reflect the impact very well,” Tooley said.

Tooley also noted breaking down the fishery into categories would be helpful in understanding impacts, including general category versus limited access, by homeport, and by small versus large boats. “I don’t think your information is to the level of detail that indicates those impacts,” Tooley said.

Hooker noted that an assessment of impacts will also include factors that are currently unknown, mainly the lessee’s construction and operations plan.

“We’re looking at it and trying to figure out how to tease out the fine-scale differences as best we can,” said Hooker.

NEFMC David Pierce wanted to know when the study of the impact of electromagnetic fields on sharks, skates, and rays will be available to the public.

“I’m curious to see if the cable will draw sharks, for example,” Pierce said.

Hooker said he expected the study to be available by mid-2017.

Pierce noted that recreational and commercial fishermen are concerned about their access to areas where turbines are set.

“How far along is BOEM with discussions regarding access of recreational and commercial fishermen to the structures within the wind energy facilities?” Pierce asked.

Hooker cited the Block Island wind facility as an example of what would occur, where there are no restrictions even for a commercial-scale project. The lessee must perform a navigational risk assessment as part of their construction and operations plan; that assessment goes to the Coast Guard.

“The Coast Guard said they don’t intend to add restrictions on Outer Continental Shelf around the turbines,” said Hooker. The only thing fishermen are prohibited from doing at the Block Island facility is tying up to the structure or impeding vessels that are servicing the platforms. “That’s what we’d expect to see offshore as well,” he said.

Pierce wanted to know if there are plans regarding the use of such facilities by recreational fishermen, specifically charter fishing boats.

“It’s always said they [wind facilities] attract fish,” said Pierce. “What might be the eventual impact to these facilities, of attracting fish and maybe benefiting the hired fishing boats?”

Hooker said BOEM doesn’t have any plan to address that scenario at the moment. “But anecdotally, we do see visits to the Block Island facility of recreational and charter head boats in the vicinity of the turbines,” Hooker said. “But I But don’t believe there’s any study at this time to look at the change in their use of the area.”

NEFMC member John Pappalardo said he was concerned about the possibility of commercial fishermen being excluded from the area.

“Where along this process is the opportunity for mitigation or compensation for displacement for the fisheries?” Pappalardo asked.

Hooker said that, once the lease is executed with Statoil, “that’s an excellent conversation to begin having with Statoil. Ultimately, it depends on what they plan on building in the area.” A problem with the process is that BOEM doesn’t know what a lessee will build until the lessee has conducted a site assessment and can determine the amount of area to be occupied by the facility, along with the type of structure and cables. Scoping and public meetings will be held during that process. In the meantime, he said, Statoil will be required to implement a fisheries communication plan and hire a fishery liaison, which will provide an avenue for the affected fishing industry and fishing communities to communicate directly with Statoil. The plan and liaison will be implemented right after the lease is signed, he said. Those communications can occur either directly or through an umbrella group, he said. “And if those pathways are not working out, BOEM can step in and…impose additional requirements, whether they be payments or what have you. But it’s our hope that most of that can happen directly between the lessee and the fishing community.”

One NEFMC member, though, said that mitigation is one of his greatest fears.

“I have sat through a number of presentation of other developers in other countries where individual fishermen are the responsible parties to negotiate with developers,” he said. Taking flounder fishermen as an example, he said, “We’re all impacted, we all negotiate separately with the developer, and we’re treated differently in the way they decide to mitigate us. That’s a concern, because there’s no policy or clear path going forward on how mitigation takes place regarding restrictions.” He suggested that, with the type of floating platform technology available today, siting wind facilities further offshore where fishery activities don’t take place would eliminate the need for any mitigation.

Hooker agreed that deepwater sites are a possibility for the future, as floating technology becomes available for a commercial-scale application. “But I don’t necessarily see some of the closer inshore sites not being developed as result of that,” Hooker said. “I see it more…as supplementing what’s done in the inshore waters.”

Bonnie Brady, executive director of the Long Island Commercial Fishing Association, asked NEFMC to review materials forwarded to it regarding the effects of electromagnetic frequency, and also of biological responses to pile driving, jet plowing and aspects of building and operating a wind facility.

“This is an entirely corrupt process,” said Brady. “We’ve been fighting BOEM because they…laid their claim and then worried about the effects afterward.”

Brady said the calculations of fishing revenue is off. “Until there’s a way to specifically and truthfully address the traditional, historical stakeholders in this process so those livelihoods don’t go by the wayside for the next best thing, we’re screwed.”

GARFO chief John Bullard said there’s no getting away from offshore wind energy.

“As BOEM enters the relatively new field of offshore renewable energy, it’s a tremendous opportunity to pioneer new ways of doing business,” said Bullard, who cited the Block Island project as an example where the communication process between diverse interests provided “the kind of conversations that led to accommodation and happy outcomes between both industries of offshore wind and fishing that you want to strive for.”

Bullard added, “There’s a tendency to compare something new, a wind enerergy area, against the status quo. But this council knows the marine environment, especially right now, is anything but a status environment. It is changing rapidly. The temperature’s changing, the pH is changing, and all kinds of things are changing. Shifting over to renewable energy is something that needs to happen, that with BOEM’s leadership is happening, and needs to happen quickly.”