What Makes a Tick

An Iconic Clock at 118 Years

by Mike Crowe

The Chelsea ship’s clock has been made the same way since 1897. The company’s most popular clock is an iconic American timepiece. Chelsea Clocks came to be known as “Time Keepers of the Sea.” Fishermen’s Voice photo

The means of measuring the time of day has changed some since the sundial. The pendulum clock, the mechanical clock, quartz clock and now the ubiquitous cell phone which now delivers the time of day to so many are part of an evolution that will likely continue.

The passing of time has not changed throughout the evolution of these technologies, but the technology to measure it has. The mechanical clock, a collection of gears driven by a spring, was first seen in China in 1260. The pendulum clock, with a precise interval dependent on the length of the pendulum’s swing, was invented by Dutch mathematician and scientist Christiaan Huygen in 1673. The pendulum clock was the most precise timekeeper until the 1930s. The first wristwatch is difficult to attribute to single individual. Huygen is also credited with it in 1675, as well as others around that time. Huygen did invent a spiral spring for a wristwatch which would in form find its way into the mechanical clock.

The deck clock with the phenolic case developed during WWII brass shortages.Thousands have been installed in US Naval vessels. Fishermen’s Voice photo

The marine chronometer, the long-sought device to measure time and longitude at sea, was developed in response to a state-sponsored contest. The first true chronometer was the life work of one man, John Harrison, spanning 31 years of persistent experimentation and testing that revolutionized naval (and later aerial) navigation. Harrison won the prize in 1737 making it possible to measure longitude accurately aboard ship and thereby taking navigation to a new level of accuracy.

The first atomic clock was built in 1949. The atomic clock is considered the most accurate today. A Swiss atomic clock built in 2004 has an uncertainty of one second in 30 million years. However, the accuracy of the quartz crystal timepiece is high and as cheap as the atomic clock is expensive.

For the last 118 years, through the development of the atomic clock, the quartz watch and the cell phone, Chelsea Clock in Chelsea, Mass., has been making mechanical clocks. During the industrial development that led up to the founding of the company metalworking precision developed to where the tiny gears and internal parts that drive the mechanical clock could be made accurately. The company makes their signature ship’s bell clock the same way they have made it since 1897. Until 2015 they made their clocks in the same brick building not far from the waterfront in Chelsea, about a mile from the USS Constitution and Bunker Hill across the Mystic River in Charlestown. They are now in a restored brick industrial building a block from their original location.

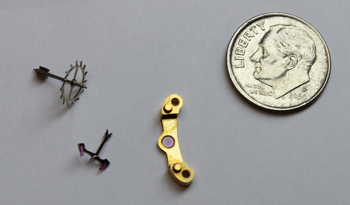

The Escapement, at center, round with coiled stainless hair spring, purple jewel bearing in the center of arm the that triggers the escape wheel gear, which in turn moves the gear train to ultimately produce a tick. Fishermen’s Voice photo

There are a lot of Chelsea clocks out there. World War II films where the US Navy was involved were bound to have a few frames with a Chelsea clock. The 24-hour “military time” clock dial, the ship’s bell clock or the Radio Room clock were all likely to have been on US Navy ships. The Chelsea brass ship’s clock mounted on a mahogany base is the most identifiable. It is the clock seen in photographs of US presidents Franklin Roosevelt, John Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson, as well as Hollywood stars and shipping industry magnate Aristotle Onassis. Navy Admiral Richard E. Byrd, Jr., used Chelsea Clocks on his expedition to the South Pole.

Some of Chelsea Clock’s fame is linked to its long history of supplying mechanical clocks to the shipping industry and the US Navy. The company produced clocks for thousands of navy vessels used during World War II, such as the USS S-36 submarine. The Navy needed clocks that were accurate, reliable and able to withstand the harsh conditions at sea during wartime.

The most popular Chelsea Clock is the ship’s bell clock with a 6” clock dial and conventional hands. But it delivers the time of day through the ship with a chime of a particular tone that signals the time – eight bells at 4, 8, and 12 o’clock mark the end of a mariner’s four-hour watch, with one bell the first half-hour after, plus one additional bell with each subsequent half-hour.

The sinking of the Titanic resulted in the Radio Act of 1912. The disaster also led to the design of a special Radio Room clock, which features two 3-minute periods marked in red to indicate a period of silence when only emergency radio messages can be transmitted. Two green markings designate periods of silence during which one must listen for coastal distress signals.

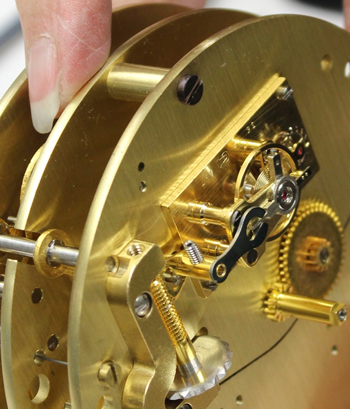

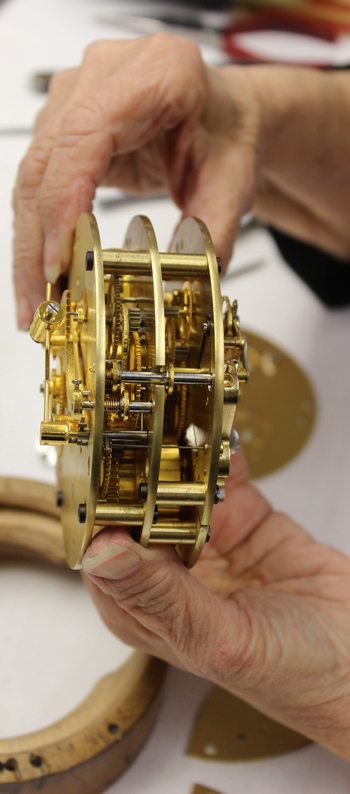

The clock works of a ship’s clock. The gears of all sizes, shafts, jewels, screws, bolts, brass, gold plate and springs- 364 parts in all- work together to produce a perfect tick. The round brass part, upper left, with a slotted screw is the bell ringer. Fishermen’s Voice photo

Originally clocks were designed and built by hand. Prior to 1800 all the parts of a clock were made by hand under the roof of one clockmaker. In the 15th to the 17th century clock making was a technically advanced trade. The best clockmakers often also built scientific instruments. For a long time they were the only craftsmen trained in designing precision mechanical apparati. A lot of that tradition lives on at Chelsea Clock and that, combined with the standards required by the U.S. Navy, is what make the product and company unique. The company has had several owners over the decades and has diversified its clock line to include quartz clocks, but the core of the business and the company image is based on the mechanical clock.

Every ship’s clock is stamped with a completion date. The owner’s name is registered with the company and all service records are maintained through any subsequent changes in ownership. In January 2016 the oldest clock in for restoration was built in 1902.

The Chelsea ship’s clock has 364 parts. They are all made the way they have been made since 1897. The materials are high quality and the quality control systems in place are what might be expected in the space program. The brass is first use brass, rather than recycled brass that may have impurities. The company has added some more modern technology to produce traditional product and appearance. The heavy brass outer case, for example, is now turned on modern computer aided lathes that turn out exact copies. That finished brass product is buffed and polished by hand.

Many other techniques are the same as those practiced in 1897. The brushed silver clock dial is an example. The brass clock face is finished and hand buffed before being lightly silver-plated. The dial is then placed on a rotary machine where it is finely brushed with a horsehair bristle brush until it passes quality control examination.

What of some physicists, philosophers and the chronically tardy, who say there is no such thing as time anyway? We’re not going back into the caves because of these time deniers. Time matters to most humans so why not get it from a device that says as much.

Pieces of it’s heart. Upper left is the escape wheel gear. The part below it is the escapement armature, the pallet, with two purple jewel pallets attached, which releases or allows tension to escape by a fixed amount, one tooth at a time via a cog, on the escape wheel gear. The escape wheel is mounted on a tiny geared shaft, allowing the clock’s gear train to advance and be expressed by the hands on the dial. The image on the coin upper right was a Chelsea ship’s clock owner and U.S. President. Fishermen’s Voice photo

The workings of the quartz clock are too abstract and mysterious and at the same time too simple. The complexity and precision of the mechanical clock are both fantastic and beautiful statements about a quest for a kind of mechanical perfection—perfection in the measurement of something that didn’t much concern humans until fairly recent industrial times. Prior to the clock or the sundial, when the sun was high, daylight was half over.

No part of the mechanical ship’s clock Chelsea makes fits the description of perfection better than the escapement.

The escapement is used in all mechanical clocks. However, seeing one operate for the first time in the context of a maze of tiny precision polished brass, gold plated and jewel parts can be startling. Master clockmaker Bob Ockenden, wearing a starched white lab coat, turned over the three-tiered brass stack of 364 gears, wheels, jewels, and screws of the inner works to reveal a part that contained yet smaller parts. In the center of this part, the size of a quarter, there was movement—a pulsing movement that mimicked the pulsing of a human heart so closely that it appeared organic in some peculiar science fiction way.

A closer look revealed that the smooth pulsing movement was made by a hairspring uncoiling and recoiling.

This metal spring was at one time made from boar bristle and has retained its name. The hairspring is put in motion by the escapement armature, called the pallet, which releases or allows tension to escape by a fixed amount, one tooth at a time via a cog on the escape wheel gear.

The escape wheel is mounted on a tiny geared shaft, allowing the clock’s gear train to advance and be expressed by the hands on the dial.

When the armature moves ever so slightly to stop the escape wheel gear it makes a sound, a tick sound, a heartbeat.

The movement’s 364 parts, including gold plated brass gears, hardened steel pinions, and jeweled bearings, are hand assembled. Mainsprings are hand wound, and the finished pieces are balanced and calibrated. In total the manufacturing and assembly of a ship’s bell requires hundreds of hand operations over a period of 6 weeks.

Assembly workstations are fitted out with bright white bench tops, mobile lamps with magnifier centers, assemblers with a series of magnifiers attached to their eyeglass frames. On the bench are specialty tools of all kinds for working with tiny objects. Screws are so small they are nearly beyond visibility with the unaided human eye. Seeing the number and size of gears packed into a ship’s clock begs the question, What do all those gears do between the ticks of a clock?

The people who build these clocks are master clockmakers. This is not at all an assembly line. Each clockmaker has a bench, equipment, tools and lighting. Their response to a question like that is preceded by a long pause before a slowly emitted, “Well-l-l,” which has to be translated as, “It’s a long story.” The clockmakers take extra care to ensure each instrument, both clocks and barometers, function perfectly. Each movement on assembly is inspected and accuracy-tested for seven days. Once it’s put into the case, the whole unit is again tested for an additional seven days.

In general, the Ship’s Bell Mechanical Clock can have a variance in timekeeping of approximately plus or minus one minute per week. This can be addressed by slightly adjusting the “Fast” or “Slow” wheel, located on the dial of the clock.

The traditional ships clock is entirely mechanical. There is no quartz or electricity in involved in it’s operation. It is wound every seven days, although it will run for eight days.

There are two keys, one for setting the clock and another for winding the spring.