B A C K T H E N

S.W. Lawrence: The Details

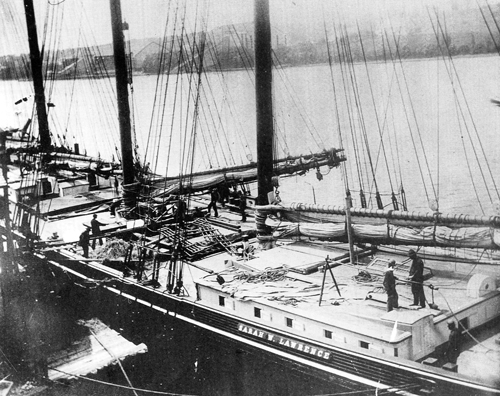

1901 or so. The Bath-built, four-masted schooner Sarah W. Lawrence, of Fall River, Massachusetts, loading ice on the Kennebec at Cedar Grove, Dresden. She is evidently almost filled. An ice-lowering machine is mounted over the hatch; a worker holds back a block of ice, waiting for the counter-balanced platform to return. Framework “runs,” tossed aside, have been used to place the ice. Swale hay “dunnage,” which will be spread over the top tier of ice to slow melting, lies on deck—hay was easier to handle than was sawdust. Aft, two sailors “serve” a length of wire rigging with tarred twine to protect against corrosion; an old sail shields the cabin top from drops of linseed oil. The sailors are likely Scandinavians, the icemen, locals. The structure at the end of the cabin, rounded to shed snagging lines, houses the compass.

It is lively at Bank street and the North river these days. Great four-masters from Maine are moored there discharging ice into the wagons of the city ice companies. Power is supplied from a convenient engine to half a dozen blocks and pulleys. Down go the big ice tongs into the vast steaming hold of the ship. A warning cry, a clatter of the shaft, a creaking of cables, and up come the shining squares, to be quickly led into a chute whence they go spinning to a long, broad platform and are seized by smaller tongs in the hands of men who stand between the people and soft butter, spoiled meats and warm drinks. How hot it is on the deck of these vessels and how cold down there! The Sarah K. [sic] Lawrence carries 2,500 tons, at $1.50 a ton, loaded in Maine.

But even with ice at $3 a ton wholesale, the companies ought not to go bankrupt, seeing that the consumer pays at the rate of $20, short weight. The Sarah K. Lawrence is usually employed in the gas coal trade between Philadelphia and Boston. An ill wind that blew up the Hudson last winter has converted her coal pockets into ice caves. Her crew as well as owners are well pleased since the companies load and unload the cargoes themselves, and between ice dust and coal dust who would not choose the former, especially as it brings more gold than dust? Those who think vessel property unprofitable should take a leaf out of the log of the Sarah K. Lawrence and others of her class. She was built in Maine about three and one-half years ago, at a cost of $65,000. Her owners are twenty in number and live in Taunton, Mass. She is managed by an agent who has a part interest in her and also looks after ten other vessels in the coasting trade. She has paid for herself more than twice over since she has been built. —New York Tribune, in The Industrial Journal, Sept. 5, 1890.

Maine’s shipments of ice to New York—indeed, the very size of Maine’s cut—depended on the success of the huge ice industry of the Hudson River. Ice from the Hudson was delivered to the city in long rafts of housed-over barges that came down with the tide with big tugs. Barges were cut out by small tugs.

The complete failure of the Hudson River ice crop in the winter of 1889-90 created a frenzied ice boom in Maine, resulting in a never-surpassed cut of 3,092,400 tons. But the summer proved cool, prices we’re kept high, and the market collapsed, ruining many plungers. Taking advantage of the confusion, Bath’s Charles W. Morse created a huge monopoly that included the principal firms serving New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. On a hot day in May 1900, Morse overreached even himself, doubling the price of ice in New York. This resulted in the sacking of corrupt politicians and the exit of Morse from the ice business ($12 million softened the blow). This also marked the beginning of the end of the natural-ice industry, which, by 1910, had been largely supplanted in the great seaboard cities by artificially produced ice.

The Sarah W. Lawrence, when new in 1885, was the largest schooner on saltwater. Like a number of early four-masters, she was a shoal center-boarder, fitted with a large, wooden drop keel. Her mizzenmast—the middle mast of the three we see here—is offset to accommodate the centerboard trunk. The Lawrence was a member of the pioneering fleet of handsome four-masters built in the ‘80s to the order and design of coastal shipping men of Taunton, Massachusetts. Between 1870 and 1895, Taunton interests owned about forty three-masters and fourteen four-masters, many built by Maine yards. By January 1894, the Lawrence had reportedly paid her owners over $200,000.

The Cedar Grove houses originally belonged to Cochran-Oler Ice Company, of Baltimore. Across the river at Iceboro, Richmond, may be seen two sets of houses belonging to Haynes & DeWitt, an Augusta-owned firm that was a major player in the Baltimore and Philadelphia markets.

Text by William H. Bunting from A Days Work, Part 1, A Sampler of Historic Maine Photographs, 1860–1920, Part II. Published by Tilbury House Publishers, 12 Starr St., Thomaston, Maine. 800-582-1899.