B A C K T H E N

Red Shorthorns

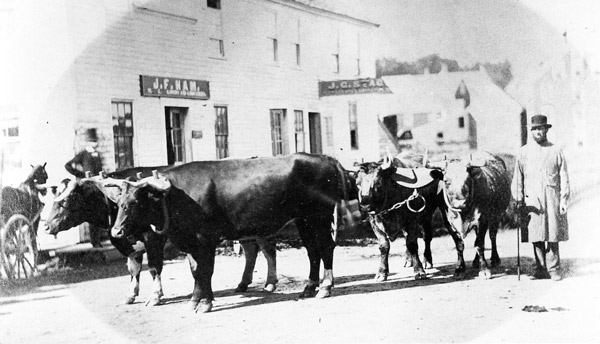

Dexter, 1860s or earlier. A yoke of red Durham, or Shorthorn, oxen, followed by a yoke of roan Durham steers and a tall ox drover in traditional long coat, likely of blue. All oxen are steers, or castrated bulls.

However, all steers are not oxen, the term “ox” being applied to cattle at least three, if not four, years old. Bulls castrated after they were sexually mature were known as “stags.” Mature, unaltered bulls were also commonly worked, although their thick necks required oversized bows, and often their great strength was not matched by great ambition. (Custom yokes were regularly made for individual teams, with varying bow size. Differing lateral placement of the staple and ring adjusted the mechanical advantage, evening out differences in individual strength.)

Oxen can be of any breed, although few “polled,” or hornless cattle were trained to the yoke since horns served to keep the yoke in place when cattle held back a load. The bow yoke used in the United States was of British origin—most Europeans used yokes lashed to the horns. The ox’s great neck strength reflected the bull’s natural inclination to face an enemy and stand and fight; stallions, by contrast, bite, kick, and run.

Here, the older and “handier,” or better-trained, oxen are the “leaders,” responding to verbal commands of the drover, who, properly, walks behind with the “tongue,” or “pole,” or ‘wheel” cattle. Cattle are generally very receptive to instruction, particularly when first trained as small calves.

I have seen the best drilled soldier mistake, for an instant, advance arms for recover arms, but never saw a well-trained ox mistake gee for haw, or haw for gee: hence, system is indispensible in the management of working cattle. — J.S. Skinner

The Durham, or Shorthorn, breed originated in the northeast of England in the late 1700s from selective mating of local cattle by men skilled in both genetics and promotion. The cattle, which could be white, nearly all red, roan, or a mix, fattened easily, milked well, were willing workers, and had a kindly and intelligent disposition. Durham bulls were said to quickly improve local cattle stock and became greatly sought after. For all the nostalgia regarding the “native” New England cattle, farmers were quick to introduce Shorthorn blood when it became available.

Maine’s famous Peter Waldo Shorthorn stock came with the capture by a privateer of a cow and bull aboard the English brig Peter Waldo during the War of 1812. Sold at Portland, their descendants were legion in Cumberland, Kennebec, and Somerset counties. The most influential Shorthorn bull in Maine was the great Denton, a descendant of the breed’s English foundation bull, Hubbock. Denton arrived in Massachusetts in 1817 as a yearling. When six years old he weighed 2,700 pounds, and even his “grade” calves sold for $200 or more. When going on twelve Denton came to Maine, a gift to the noted agricultural reformer Dr. Ezekiel Holmes of Gardiner, to continue his good work for several more years.

The Kennebec Valley became the leading Shorthorn district. In 1860, Samuel Boardman described the stock of Somerset County, evidently heavily Shorthorn, as being unexcelled in “beauty of form and color, large size, and good working qualities.”

They are usually purchased of farmers, in the fall, for the business of lumbering, and after being worked in the swamps two years, are fattened for beef. The work upon farms is chiefly performed by ox labor, and it is proved to be better, cheaper, and safer.

An agricultural authority of the ‘60s wrote of American oxen:

No laboring beast is so much abused—not excepting the mule—as the ox. His patience, endurance, and fidelity under rough usage, gives many a hard and neglectful master, who sins either through ignorance or brutality, against the generous nature of the brute, when care and kindness would add both to his utility, and profit. —Lewis F. Allen, 1886.

Oxen likely fared better in New England than elsewhere—the Southwest was said to be a heaven for men and dogs, and a hell for women and oxen. But many a hard-bitten Yankee stinted the feed and applied the bloody brad with the worst of them, particularly during New England’s long drunk on West India rum. The sign for J. F. Ham’s store advertises “W. I. Goods and Groceries,” the standard euphemism for rum and molasses. These cattle, however, look to be fat, pampered, and content.

Text by William H. Bunting from A Days Work, Part 1, A Sampler of Historic Maine Photographs, 1860–1920, Part II. Published by Tilbury House Publishers, 12 Starr St., Thomaston, Maine. 800-582-1899.