B A C K T H E N

The Great Inshore Fisheries

The small schooner pictured is the type used in the coastal fishery around the 1860s. A logbook from a vessel about this size that sailed out of Jones Cove on Frenchman’s Bay was part of the UNH study. Image courtesy of the William Burgess Leavenworth Postcard Collection.

BDURHAM, N.H. – An interdisciplinary team of researchers from the University of New Hampshire has published findings in Fish and Fisheries showing that Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) landings in the Gulf of Maine were twenty times greater in 1861 compared to today’s catch.

Using fishermen’s logbook data from Frenchman’s Bay, Maine, and other New England communities, the team of fourteen fisheries scientists, social scientists and historians estimated that 78,000 metric tons of cod were caught in the Gulf of Maine at the time of the Civil War. They also found evidence about the conditions of the marine ecosystem that supported these cod. Most of the fish were caught near shore, attracted by huge schools of herring and menhaden, and by abundant bank clams. However none of the logs suggested that the cod ate lobsters. This suggests that abundant cod and lobster populations might be able to exist in the Gulf of Maine at the same time. These conditions may inform management plans aimed at restoring the Gulf of Maine marine ecosystem.

The findings are an important step in being able to better implement what is known as an ecosystem-based management approach to restoring depleted fisheries. Writing in Fish and Fisheries, the researchers note that “since 2000, virtually every major assessment of ocean policy has called for implementing an ecosystem approach to managing marine resources,” but crafting such an approach has proven difficult. As populations of over-fished species decline dramatically worldwide, marine ecosystems exhibit less and less of the abundance and complexity found in the past. Yet, historical data are hard to assimilate into complex ecosystem models.

“Fishermen have always been keen observers. Frenchman’s Bay fishermen 140 years ago provided daily catch numbers in their logs, and they also described the ecosystem that supported cod in such abundance. Our work shows that not only are catch data important, but the descriptions provide significant information about the marine environment,” says lead author Karen Alexander, a researcher with the Ocean Process and Analysis Laboratory of the UNH Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space.

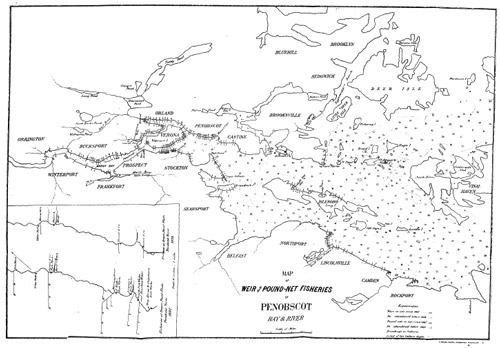

Map of Penobscot Bay weirs, pound nets and traps,

from the US Fish Commission volume 2, of 1872-73.

Lines perpendicular to shoreline indicate weirs.

Historian Jeff Bolster, an associate professor of history at UNH, notes that “the Fish and Fisheries article is the most interdisciplinary of any historical fisheries paper published to date.” It represents one of the first times a working group has described a historical ecosystem using landings records.

Using logbook data of Gulf of Maine fishermen, the researchers estimated cod landings in the Gulf of Maine in 1861, established a population structure for cod at that time, and mapped the geographical distribution of a fleet that minimized risk and cut expenses by fishing inshore where cod and bait species were plentiful.

Alexander adds, “Ecosystem-based management needs long-term, place-based data on species interactions, such as predator-prey relationships, in order to be successful. Policy-makers also need to know how people have affected the Gulf of Maine over time, and what benefits they’ve gotten in return. Historical information provides the background we need to make good decisions about the future. It encourages us to set high goals for restoring cod and other marine species vital to a healthy Gulf of Maine ecosystem and also to a healthy fishing economy.”

Originally published in December 2009 by David Sims, Science Writer for the UNH Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space.

More Abundant Than We Knew

Block Island landings from a half day of fishing sometime before 1915.

In the years 1887, 1888, 1889, 1898, 1902, 1905 & 1919, the “Shore Fisheries” so-called, were tabulated separately from the offshore vessel fisheries for each New England state. The shore fisheries were generally day fisheries, conducted within sight of land or within two or three hours’ run under sail from the nearest harbor of refuge, and were tended by small vessels and boats under 5 tons, at that time propelled by oar and sail. In 1870, Penobscot Bay alone had over 180 weirs and pound nets, but we don’t have the returns for the state that year except from the fish inspectors. For the 7 years enumerated above, Maine’s inshore fisheries caught more than 50% of the total Maine landings by weight, and except for 1902 when the herring catch was exceptionally large, that was true even when herring were omitted from the equation. The ratio of shore catch to total catch varied from Maine to New Hampshire to Massachusetts, but the Massachusetts variety of species caught inshore was remarkable in those years—the swordfish and tuna catches were mostly shore fishery products.

— William Leavenworth