Marine Archaeology on the Passagassawaukeag

by Tom Seymour

Remains of a wooden ship on the banks of the Passagassawaukeag River in Belfast, Maine. Local high school students established an archaeological dig at the site. Tom Seymour photo

Belfast Area High School history teacher Chip Lagerborn offers students an optional, one-semester, archaeology course. Each fall, Lagerborn’s students visit a scuttled sailing vessel at the bottom of the Passagassawaukeag (Passy) River in Belfast. This is an elective course and students greet it with great enthusiasm.

Lagerborn’s course covers not just marine archaeology, but everything that an archaeologist might touch upon, from prehistoric times to the present day. The course includes field trips and students visit the Maine State Museum in Augusta. But the highlight of the course comes the day the class leaves school and travels the short distance across the Passy River to the site of the old vessel. The vessel lies in a shallow part of riverbed and at low tide, is fully exposed.

“Part of the reason the students like this so much is that it’s local. Local history appeals to them. After all, many of them grew up here and their parents and grandparents before them were raised here,” Lagerborn said.

Lagerborn himself is no stranger to marine archaeology. He once volunteered to do marine archaeological work for the University of Maine, his Ala Mater. While in the field, Lagerborn participated in the discovery of a colonial-era fort along the Penobscot River, just above Veazie. Artifacts dated the fort to the time of the American Revolution and Lagerborn and his fellows determined that the fort was abandoned just after the British seized Castine.

Following the disastrous defeat of the American navy at Castine and subsequent retreat, abandoning and destruction of American ships and smaller craft, the Penobscot River was open to marauding British, making the fort at Veazie impossible to properly defend. Therefore, the Americans left the fort and burned it to prevent it from falling into British hands.

Before going on, readers will remember that my last several contributions to this newspaper were about Maine’s granite industry. I ended with a piece on Douglas Coffin, a stone carver from Belfast. This story about students at Belfast High studying marine archaeology ties in with its predecessors and serves to tie the granite stories up in one, neat package.

The Wreck

Chip Lagerborn learned of the wreck on the Passy River from a fellow teacher at Belfast Area High School. This teacher lives along the river and the remains of the wreck, mostly ribs and the keel, among a few other smaller bits, lies just a short distance from his house. Lagerborn was keenly interested in this and immediately made plans to incorporate studying the wreck into his history class.

And so the students got to do some field work in marine archaeology. They visited the wreck, but before that they were instructed in what to do and what to look for once they arrived. This included learning about how to set up a dig, meaning setting up a grid and working on a mesh pattern.

“Every little thing tells a story,” Lagerborn told his class. “The more information in hand, the better.” And so the students were more than adequately prepared the day of their visit to the site. They arrived with pencil, notebook and sketching pads in hand.

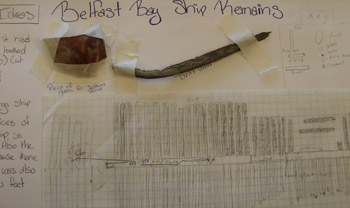

Some of the data collected and recorded about the ship in the river mud in Belfast. A sketch of the vessels ribs below. A piece of glass left and a metal nail right recovered from the vessels remains. Tom Seymour photo

Each student was required to document what he or she saw and found. This varied slightly, since some had located bits of metal and other small artifacts and others didn’t. However, all got to examine the layout of the ship’s skeletal remains. And each student drew a representation of it on their pads. Lagerborn had the student’s findings and their sketches on display the day of our interview and it was pleasing to note the great detail shown in many of the sketches.

However, since everyone sees the same object with different eyes, the layout varies slightly from one student’s work to the next. A compendium of these, though, gave a solid overall picture of how the ship’s remains actually appear.

Upon arriving at the site, the students broke up into teams. Each team included someone to take notes of everything that went on, another would take measurements and another was tasked with recording the dig. Not a thing differed from the way a professional archaeological dig would commence. In fact, Lagerborn said that his class was an introduction to a career in archaeology. As such, the old wreck on the clam flats of the Passy River plays a substantial part.

So given their findings, and piecing everything together with what they knew and what they might discover, the students were told to write their own hypotheses. And each one did. These were displayed along with the sketches that Lagerborn showed me. Some students even attached old nails, bits of metal and other objects from the site in order to help substantiate their hypotheses.

The Conclusion

The students were able to establish some interesting facts about the wreck. While it was impossible to find a name for the wreck, they did learn that it was from around the turn of the 20th century. This, they determined, from the timbers, which exhibited machine saw marks. Such machine-sawn timbers, as opposed to hand-sawn timbers of the 18th and early 19th centuries, were sufficient to establish a general date of construction.

It was also learned that the wreck had been picked clean after it was abandoned. Most metal parts were taken and probably scrapped, as was any useful item that was not too large and heavy to carry.

Also, the site itself was found to be a place where other ships and boats were similarly abandoned. In fact, parts of another wreck lie very close to the one featured here. Lagerborn has plans to don scuba gear and do some further exploring up the Passy, in hopes to locate even more wrecks.

Returning to the students and their findings, it was determined that the wreck was that of a small schooner. In fact, the schooner had been patched and repaired many times over its working life. This might indicate that it saw hard use. That conjecture was substantiated by the closeness of its ribs.

“Why,” Lagerborn asked his students, “were the ribs so close together?” This feature was a huge clue as to the ship’s use and employment. The answer was that the ribs were close together to make the hull stronger in order to carry heavy loads. But what kind of loads?

Now the picture comes full circle. The Passy River was, back in the late-19th and early 20th-centuries, home to a number of landings, or places where materials were carted down to the water and loaded upon ships. Just a bit upstream from the wreck site is a place still known as “Board Landing.” Indeed, there were brick landings, board landings, hay landings and most of all, granite landings. The students had correctly determined that the wreck on the Passy was the remains of a rugged, little schooner used to haul granite, probably granite from nearby Oak Hill Granite Quarry.

So in ending this story about marine archaeology, we also resolve and conclude the several previous stories about the Maine granite industry.

Anyone driving along Kaler Road in East Belfast at low tide can see the remains of the wreck talked about in this story. It is just as much a part of the long-vanished granite industry as are the blocks of granite found in breakwaters, buildings and monuments all around the country.