B A C K T H E N

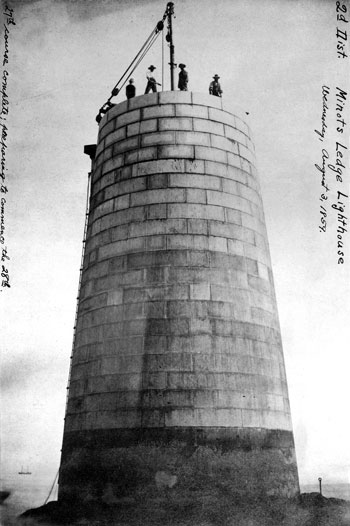

Minot’s Ledge Light

Because lighthouses live in the tumultuous and changing locale of the seashore, they must be built to forms unlike the ship or the house. Waves and tide assault the shore and tear down any structure built there, and when the building must be tall, as the lighthouse need be, then the problems faced by architect and builder are great.

The tower of the Minots Ledge light is cylindrical — one practical shape for a lighthouse. The wind and sea, both of which will strike the house, can come from any direction, and the form of the building must offer the least resistance to their attack. If we knew that waves would only arrive from a single point of the compass, then we could build a knife-edged house facing that way, like the Swiss buildings in avalanche country which present an acutely angled edge to the rising slopes upon which they are built. The sea, however, is unpredictable, and her assault can come from north, south, or any direction in between. Only with a cylindrical shape can we know that the building will handle an onslaught best, no matter from which direction it comes.

These blocks are held together with mortar, the glue of the mason’s world, and the flat horizontal surfaces are mated with a wide joint of cement, to hold the chunks together to form a single massive structure. While the mortar helps, the chief binding force of the building is gravity, and this tall tower is actually just a highly refined pile of rock. Another of these carefully finished and tall rock piles is the Washington Monument, which often adorns postcards from our nation’s capitol.} These two shaftlike buildings, one round and the other of square cross section, depend upon the density of stone in the grip of gravity to achieve their strength and stability.

The stones are being pulled up to their final resting places by a gin pole. This simple and ancient lifting device consists of an angled pole that leans out from its pivot to a point beyond the building’s edge. From its tip is suspended a block and fall that can reach down to the ground and lift each successive block. The gin pole is strong and light, and as the building grows this crane rises with it. The little stick and its lines, that we see here at the top of the partially constructed lighthouse, are thus the precursor of the steel cranes that dot the landscape of all large cities today, as they grow up into the sky to keep above the working surface of the buildings that they are steadily creating.

Photo courtesy Newport News Mariner’s Museum. Text courtesy Yale University Press.