Anatomy of a Shop Contract

by Nicholas Walsh, PA

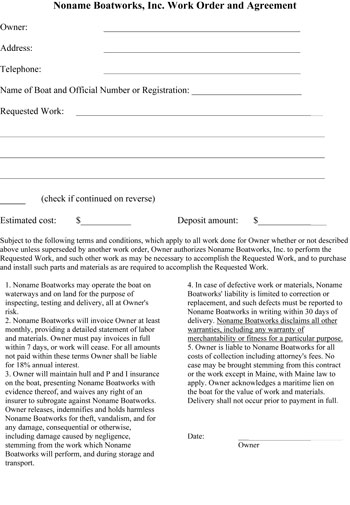

Over the years I have carefully honed a shop contract, and in this column I’ll share it with you. Regular readers know that my bias is toward clear, readable contracts which the parties can understand without having to hire an English major. A contract that doesn’t get signed is useless, and a complicated, maybe multi-page contract is much less likely to get inked than one on a single page and to the point. At the same time, certain provisions are absolutely necessary. That’s the challenge of drafting a good shop contract.

The first section is self-explanatory. The list of work to be performed should be as detailed as possible, to avoid misunderstandings. This contract does not have a provision for change orders, but written confirmation of changes to the work are a really good idea. Change orders can be emailed, so long as there is a return email indicating assent.

The first paragraph (“Subject to…”) authorizes the work and authorizes the yard to purchase parts and materials to do the work. Usefully, it also applies to “all work done for Owner whether or not described above unless superseded by another work order.” That is sort of a fail safe provision: If the yard, as is not unusual, goes on to do lots of work for this owner over the years without ever inking another contract, the yard-friendly provisions of this contract continue to apply.

Paragraph 1 makes express that the yard can operate and test the boat, at owner’s risk. Paragraph 2 provides payment requirements and says work can stop if payment is not made in accordance with terms.

Paragraph 2 also provides for the owner to pay interest on past due invoices. Here’s why that’s important: without an interest provision, you cannot get interest. So if you have to chase some guy and don’t get paid for a year, or maybe sue him and get paid in three years, all you can get is your money, no interest–unless your contract says so.

Paragraph 3 allocates who will get the insurance (the owner), what kind it will be (Hull for boat damage, Protection and Indemnity for injuries). It might usefully also provide for the amount of P and I insurance, typically $1 million. Perhaps the policies will also name the yard as an additional named insured, always a good idea. And be sure you get a declarations page faxed or emailed to you showing that the coverage exists.

Paragraph 3 also has a waiver of subrogation clause. If an insurance company pays you $10,000 for a claim, it “owns” your claim to the tune of $10,000. That’s subrogation. Check out any policy, even health insurance, and chances are you’ll find a subro clause. It doesn’t do any good for a yard to insist that the boat owner insure the boat against loss if the owner’s insurance company can turn around and sue the yard for negligently causing the loss, so a waiver of subrogation clause is important. If you are on the policy as an additional named insured, the subro issue doesn’t exist.

There are other ways to handle insurance. A sophisticated commercial construction contract will identify areas of risk (workers comp, tools and materials at the site, loss of structure, injury to third parties, etc.) and state who, owner or contractor, will obtain insurance for each risk. The parties agree not to claim against the other for any risk which is covered, and they waive subrogation. That way everyone knows where they stand.

Paragraph 3 also contains the owner’s waiver of any right to claim against the yard for loss to the boat. You may ask why this clause is in the contract, given that there is an insurance clause already, but sometimes insurance coverage is denied - or the policy never existed, or was cancelled. A second line of defense is a good idea.

Lots of shop contracts contain a release clause, but lots of those clauses are faulty and can be defeated in court with little effort. It is key that the clause state that the release is effective even for damage caused by the yard’s negligence, using the word “negligence.”

Paragraph 4 is warranty language. Maybe you warrant your work for a year, maybe you have other provisions. My language is very yard friendly.

The underlined language says the owner won’t claim that you knew exactly what he was going to do with the boat, or maybe the components you bought for the boat, and that your choice was wrong. (I’m simplifying here.) So suppose you install a diesel in a lobsterboat and the owner goes scalloping and doesn’t have enough power and comes back to you. This clause will be a big help.

Paragraph 5: Just as you can’t charge interest with a written provision, you cannot get your attorney’s fees without a writing. If you are suing for a few thousand dollars attorney’s fees will quickly make the battle uneconomical if there is any sort of genuine dispute. Conversely, an attorney’s fees provision makes the dispute pretty high stakes for a boat owner who is reluctant to pay.

This contract has a choice of law and venue clause: suit can be brought only in Maine, with Maine law to apply. There’s a world of difference, for a small shop, between getting sued in Florida and having to hire a high priced lawyer down there, and getting sued in a local court where you can use your own lawyer. I consider it one of the most important clauses in my shop contract.

By the way: Don’t use this contract without consulting a lawyer. I’m happy to discuss your shop contract.

Nicholas Walsh is an attorney specializing in maritime law and waterfront matters. He can be reached at 772-2191, or nwalsh@gwi.net.