Glass Eels: Big Rewards, More Regulations

continued from Homepage

Fyke net set in Somesville, Maine. Elvers collect in the narrow end at the far right. Laurie Schrieber Photo

MEFA disagrees with both agencies, saying the American eel stock is not depleted or endangered.

In the meantime, the state has been in a dispute with the Passamaquoddy Tribal Council, which issued more than twice the number of elver fishing licenses than the state has allotted for the tribe.

In 2012, Maine elver fishermen earned nearly $38 million for 19,000 pounds of landings. The 2012 elver fishery was second only in value to the lobster industry. During the height of the 2012 season, elvers were valued at approximately $2,600 per pound; throughout the season, the price averaged around $2,000 per pound.

In 2011, landings were 8,500 pounds worth $7.6 million. In 2011, Maine elver fishermen earned nearly $900 per pound after demand spiked in Asia following the Japanese tsunami. In 2010, landings were 3,100 pounds worth $584,000.

For 2013, dealers are now offering fishermen from $1,700 to $2,000 per pound. Five thousand Mainers applied for one of the four elver-fishing licenses available for 2013. The new licenses were issued to replace those individuals who did not renew theirs in 2012.

Declines in European and Asian eels are driving the export fishery.

MEFA met recently in Ellsworth to discuss LD 632, An Act To Improve Enforcement Mechanisms to the Elver Industry and To Make Technical Changes to Maine’s Marine Resources Laws. Given the high price of the product and the poaching that has occurred as a result, the bill was designed to discourage offenses by criminalizing them, stiffening penalties, and creating documentation mechanisms that can demonstrate legitimate links between harvesters and dealers.

Up to now, the fine for illegal possession of elvers in Maine has been up to $2,000. LD 632 imposes a system that includes $2,000 fines, mandatory suspension, and mandatory license revocation for first and second offenses pertaining to gear molestation, untagged gear, and fishing during a closed period.

Fishing without a license involves a $2,000 fine and loss of eligibility for the elver license lottery for one year, for the first offense; and a $2,000 fine, permanent loss of eligibility for the lottery, and it becomes a criminal offense which could result in jail time, for the second offense.

The bill requires a harvester to provide, upon request of a law enforcement officer or elver dealer, a government-issued identification with the harvester’s photograph and birth date. The bill restricts the form of payment for the sale of elvers to a check.

“The incredible amount of money in this fishery warrants a more stringent penalty because fines often don’t amount to one pound of elvers,” Department of Marine Resources (DMR) commissioner Keliher said in a press release.

The DMR said harvesters should be aware that “if they have existing elver violations on your record, these violations will count as their first offense under this new law. If they are convicted of another elver violation during the remainder of this season, it will count as their second offense.”

Cash Sales

At the MEFA meeting, executive director Jeffrey Pierce said a controversial aspect of LD 632 is its ban on cash sales which, up to now, amounted to cash transactions of tens of thousands of dollars from dealer to harvester.

“There’s going to be some growing pains with this,” Pierce said. “Know your buyer, know your bank. If you’re dealing with a small bank, you take a $50,000 check in, they say we can’t cash it, if you have an account there, you might have to have it put in your account. There’s a paper trail for this check now.”

One buyer said she arranges with her bank ahead of time to have money available for harvesters to be able to immediately cash the checks that she gives them.

Pierce and others warned that harvesters trying to cash large checks will doubtless run into IRS reporting requirements at the bank.

One man said the ban on cash will create hardship for harvesters, because it won’t promote competition.

Pierce said the measure is essentially an anti-poaching bill. “There used to be 18, 20 buyers” in Maine, he said. “There are 104 licensed buyers in Maine right now.The cash doesn’t show how they got to possess the eels.”

Pierce said Maine must overcome its stigma as a place where poaching thrives. He predicted that, once the current season is over, the legislature will fine-tune the law when it returns to session in the fall.

Mitch Feigenbaum, co-owner of the Delaware Valley Fish Co. in Norristown, Penn., and an eel fishery advocate, said the big fight will be with the ASMFC where, “basically, 14 other states are looking at Maine with jealousy and resentment. They’re jealous you have a fishery and they don’t have it.”

Feigenbaum said Maine is plagued by “fly-by-nighters” from other states, who may be fostering illegal fishing. “Every single state is saying the same thing, poaching is out of control, and they’re tired of paying for it when we’re getting all the benefit,” Feigenbaum said. “’Shut ‘er down,’ that’s what they say in the other states. I’ve been lobbying on behalf of dealers for more than nine years. Both glass eels and big eels along the coast. I’m right now working very hard to make sure that I know every state – who are the commissioners, what’s their attitude, are they friendly, are they the enemy, are they on the fence. And all the work we’re doing is to [talk with] the guys on the fence. It’s a political process.”

Feigenbaum urged industry members to visit the American Eel Sustainability Association website (americaneel.org), which posts the latest news on the fishery.

“My organization does not claim to speak for glass eel fishermen, it doesn’t claim to speak for big-eel fishermen,” he said. “It just claims to lay out the information so everyone has access to the information, so we can prove to the public that the eel stocks are in good shape and that there’s no reason for this nonsense about endangered listing, let alone closing our fishery.”

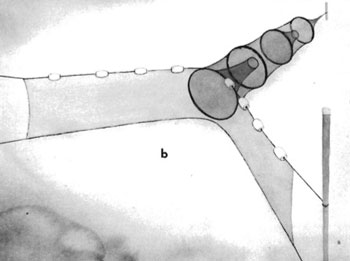

Fyke net used to harvest elvers. The net is allowed to span only a part of the area where a stream enters a marine estuary. NOAA Graphic

Eel Life Cycle

The American eel spawns in the ocean and migrates to fresh water to grow to adult size. As adult eels mature, they leave the brackish/freshwater growing areas in the fall, migrate to the Sargasso Sea and spawn during the late winter. The Sargasso Sea is a large area of the western North Atlantic located east of the Bahamas and south of Bermuda. After spawning, the adult eels die. The eggs hatch after several days and develop into larvae, which drift in the ocean for several months and then enter the Gulf Stream current to be carried north toward the North American continent. As they approach the continental shelf, the larvae transform into miniature transparent eels called “glass eels.”

As glass eels leave the open ocean to enter estuaries and ascend rivers they are known as elvers. This migration occurs in late winter, early spring, and throughout the summer months. Eels may stay in growing areas from 8-25 years before migrating back to sea to spawn.

“There are three distinct fisheries for eels in Maine which relate to three different life stages,” the DMR continues. “The glass eel/elver fishery harvests small eels returning to rivers from their ocean spawning areas. This fishery utilizes fine mesh fyke nets (a funnel shaped net) or dip nets to collect elvers as they ascend to fresh water.

The yellow eel fishery occurs for eels which are growing in brackish and fresh waters. These eels are typically more than 2-3 years old, but not yet mature. Harvesting gear in this fishery includes baited eel pots and fyke nets.

The silver eel fishery occurs in late summer and fall and consists of weirs across streams and rivers to collect out migrating sexually mature eels that are moving downstream to go to the Sargasso Sea to spawn.

“Fisheries for yellow and silver eels have a long history in Maine, having occurred since the earliest colonial settlements. The elver fishery is relatively recent, having begun in the early 1970s to 1978 and recommenced in the early 1990s. In recent years, market demand has increased dramatically.

Elvers are highly valued in the Far East (Japan, China, Taiwan, and Korea) where they are cultured and reared to adult size for the food fish market.”

Legislation passed in 2006 eliminated new entry into the fishery by instituting a license lottery. Currently an elver-fishing license may be issued only to an individual who possessed a license the previous year.

Glass eel fisheries currently occur in Maine and South Carolina. Significant yellow eel fisheries occur in New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, the Potomac River, Virginia and North Carolina.

“From a biological perspective, much is still unknown about the species. Information about abundance and status at all life stages, as well as habitat requirements, is very limited. The life history of the species, such as late age of maturity and a tendency for certain life stages to aggregate, can make this species particularly vulnerable to overharvest”, the ASMFC said.

The only sea without a coastline, the Saragasso Sea is an area of the Atlantic Ocean with large amounts of a saragassum seaweed on the surface. The sea is bounded by ocean currents. NOAA Map

The Last 10 Years

In 2004, the USFWS and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) received a petition to list the American eel as an endangered species. The petitioners cited “destruction and modification of habitat, overutilization, inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms, and other natural and man-made factors (such as contaminants and hydroelectric turbines) as the threats to the species,” according to the USFWS’s Federal Register notice.

The USFWS subsequently noted that it, not NMFS, has jurisdiction over the American eel. In 2005, the USFWS found the petition presented “substantial” information indicating that listing the American eel may be warranted.

But in 2007, the USFWS found an endangered or threatened listing was not warranted on all issues, except climate change, which it would evaluate further.

In 2010, USFWS received a second petition from Craig Manson, executive director of the Council for Endangered Species Act Reliability, to list American eel under the ESA.

In 2011, the USFWS found the petition presented “substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that listing this species may be warranted,” and subsequently initiated a status review, which is ongoing. Climate change and its potential impacts were among the concerns mentioned in the finding. These included factors such as sea surface temperature and the relationship of food availability to survival of eel larvae in the Sargasso Sea and along its migration up the Atlantic coast, and possible threats to the Sargasso Sea that might affect glass eel recruitment as a result of climate change.

In the meantime, the ASFMC’s 2012 benchmark stock assessment found the American eel population is depleted in U.S. waters. “The stock is at or near historically low levels due to a combination of historical overfishing, habitat loss, food web alterations, predation, turbine mortality, environmental changes, toxins and contaminants, and disease,” the ASMFC said.

According to the ASMFC, “The seeds of the current depletion lay in part in a fishing up/fishing down episode that occurred on American eels in the 1970s into the 1980s as export demand rose. Roughly during the same period, river damming intensified and hydroelectric facilities on dams caused additional mortality. A suite of stressors including habitat loss from dams or urbanization, turbine mortality, the non-native swim-bladder parasite Anguillicolla, toxic pollutants, and climate change are all factors that act in concert with fishing mortality on American eel.”

The assessment reports that, although the glass eel fishery is regulated in Maine, poaching “is a serious concern in many states, including Maine.”

A few ounces of glass eels. Asian markets grow them out to market size silver eels. Full grown they are a high value market food in Asia and Europe. Depleted glass eel sources there have driven up prices here.

Addendum III

Draft Addendum III “proposes a wide range of management options with the goal of reducing mortality and increasing the conservation of American eel stocks across all life stages,” the ASMFC said. “Specific management options focus on both the commercial (glass, yellow and silver eel life stages) and recreational American eel fisheries. The document also proposes increased monitoring by the states and recommendations to improve American eel habitat.”

(For the draft addendum and comment guidelines, visit asmfc.org under Breaking News or call 703.842.0740. The comment deadline is 11:59 p.m. on May 2. A hearing on Draft Addendum III will be held April 30, 1-5 p.m., at the Augusta Armory, 179 Western Ave. FMI: Terry Stockwell, DMR, 624-6553; Kate Taylor, ASMFC, 703-842-0740.)

“Our biggest hurdle is Addendum III,” Pierce told the MEFA gathering. “We can’t argue that their statistics are wrong, because we’ll lose that battle,” said Feigenbaum. “What we can do is say that their statistics are only telling the story in a very small context, and the big picture is a much more favorable one.”

Feigenbaum said it will be important to demonstrate that, even with fishing effort, the numbers aren’t going to get out of control.

“You can’t have millions and million and millions of glass eels coming in year after year after year if there isn’t a huge population of adults out there in the Sargasso Sea making them,” Feigenbaum said.

Pierce said, “We’re not opposed to regulations. That’s common sense. But they should have state flexibility built in. Addendum III is coastwide, one solution fits all, but there are lot of different geographical differences from Maine to Georgia, and a lot of different river situations. So we’d like to see state flexibility. It’s really unfair for us to tell Maryland to give up their yellow eel fishery because we’re wiling to give ours up. But it’s unfair for them to tell us to give up the glass eel fishery because they don’t have one.”

Pierce said Maine should also be recognized for its initiatives to improve habitat that help the American eel, such as removal of dams and improvements of fish passages.

“The fact that Maine licensed fishermen caught nearly $38 million worth of elvers in 2012 and broke the previous record by more than $30 million in itself provides a different view, and we feel that in Maine it is not depleted and it is a positive factor in our state economy,” MEFA said.

MEFA said that, currently, there is only a limited amount of scientific data collected about juvenile eels that could prove useful to future management efforts. “Maine elver fishermen can collect and provide bycatch information to regulators and scientists and we would like to see more scientific studies on elver migrations,” MEFA said.

As part of its mission, MEFA said, it “intends to do what it can to discourage illegal poaching, which has increased since the per-pound price has soared, but the main importance to our group is to promote sustainable management of the species.”

According to MEFA, many elver fisherman also have licenses for harvesting American eels during their later life stages, “but to promote ongoing protection of the species the consideration of eliminating those fisheries in Maine should be evaluated.”

Tribal Licensing

On a separate but related topic, the DMR said in a series of press releases it hopes to resolve a licensing dispute with the Passamaquoddy Tribal Council.

On March 29, a week after the elver fishery opened, the DMR said it received a list of tribal members to whom elver harvesting licenses had been issued by the tribe. “This list included 575 names, numbered sequentially,” the DMR said.

Under recently enacted LD 451, the tribe is authorized to issue 200 licenses. The Maine Marine Patrol subsequently encountered Passamaquoddy tribal members in Pembroke fishing without valid licenses “and took appropriate action by confiscating gear that may result in issuance of summonses,” the DMR said.

According to the DMR’s background statement, in 1997, the Passamaquoddy Tribe obtained the authority through a change in state law to issue licenses for the harvest of marine resources to its members, subject to the same laws applicable to state license-holders. At the time, lobster and sea urchin were the only limited entry fisheries, and the tribe was allocated a fixed number of licenses for each of those fisheries.

Since then, the elver fishery became a limited-entry fishery. But the law regarding the Passamaquoddy licenses was never amended to reflect the need to cap licenses “at an appropriate level,” the DMR said.

“In 2011 and 2012, licenses for the Penobscot Nation and Aroostook Band of Micmacs, respectively, were capped at 8 licenses each,” the DMR said. “In 2011, the decision to not cap the Passamaquoddy Tribe was not particularly problematic, since they only issued 2 commercial elver licenses that year. However, in 2012, following the start of the elver season, the Passamaquoddy Tribe issued 237 licenses to their members, each for up to 2 pieces of gear (a fyke net and a dip net).”

As a result, LD 451 was enacted.

The tribe’s fishery advisory council has separate management measures in place, including a catch cap of 3,600 pounds for 2013 and additional restrictions and monitoring requirements.