B A C K T H E N

Fish River Railroad

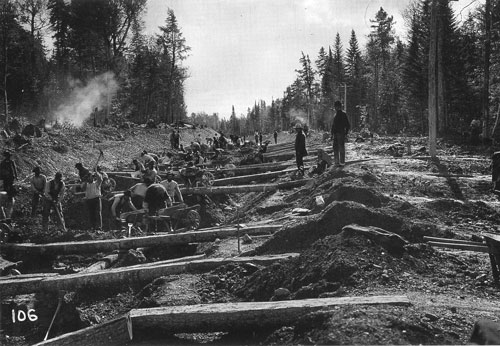

A wonderful photograph, found in the Houlton dump, showing the grading of a cut on the Fish River Railroad.

The Fish River was a fifty-eight-mile extension of the Bangor and Aroostook’s Ashland Branch to Fort Kent intended to capture additional timber of the watershed of the St. John. Two thousand laborers, mostly Italians, completed the line in one year’s time during 1901 and 1902.

The photo may have been taken by Moses Burpee, the road’s chief engineer and surveyor. Surveying a right-of-way through forested “wildlands” before the day of topographical maps was no small achievement. The seemingly primitive spectacle of building a railroad by muscle power and blasting powder (dynamite, actually; two steam diggers were also employed) was, in fact, a thoroughly familiar process. By 1900 American contractors had built well over 200,000 miles of trackage in this country, as well as many foreign roads.

Regarding the use of wheelbarrows in railroad construction, an 1899 railroad engineering handbook noted:

© Wheelbarrows. Gillette has computed from observations that a man will trundle a wheelbarrow at a rate of 250 ft. per minute or 1.25 stations of lead per minute for the round trip. The time required for loading is estimated at 2 ¼ minutes and for unloading, adjusting wheeling planks, short rests, etc., ¾ minute, or a total of 3 minutes per trip for all purposes except hauling. Gillette allows for a load of only 1/15 cu. yd., measured in place, or about 1/11 yd., 2.5 cu. ft., on the wheelbarrow. With notation as before, and for a ten hour day.

Cost per cubic yard of loading and hauling earth in wheelbarrows = Cx15(1.25s+3)

600

In this equation C is the per-day labor cost, to which should be added about 5% for the cost, repairs and depreciation of the wheelbarrows, whose service is very short-lived.

A hundred years earlier, the wheelbarrow had been high-tech. In 1793, in Massachusetts, construction was begun on the twenty-six-mile Merrimac Canal from Boston to Lowell, intended, in part, to tap supplies of New Hampshire ship timber. Massachusetts had many able and practical men, but none who knew anything about building a canal, and there were no books on the subject. The Romans had built great aqueducts, and in the 1600s the French had built a canal 148 miles long, containing 119 locks, and rising 620 feet above sea level, but anyone building a canal in Massachusetts in 1793 had to start from scratch. Correspondence was initiated with an English engineer, John Rennie, who advised, among other suggestions, the use of wheelbarrows where earth was to be carried less than thirty yards.

The vital business of establishing grades required more than the native wit of even the most level-headed Yankee. Bookseller/artilleryman Henry Knox (of Revolutionary War and Knox County fame) urged that grades be established by eye, which resulted in an accumulated error of forty-one feet over a six-mile stretch. Yankee know-how was going nowhere. The project was saved by English engineer William Weston, who had come to Pennsylvania to consult on a canal project. Weston (the father of American civil engineering) spent two weeks with canal superintendent Laommi Baldwin (the father of the Baldwin apple). Weston shared construction techniques, the design for an improved wheelbarrow, and – most importantly – his transit.

The seeds of knowledge planted by Weston led to the Erie Canal in the 1820s. This epic project altered the geography, economy, and self-image of America, and served as a great practical school of engineering, whose graduates were at the forefront of the developing age of railroads. (The matter of determining accurate grades is very nearly as critical when building railroads as when building a canal. The ability to accurately lay out curves is also vital. The first formal American school of civil engineering was the military academy at West Point.)

Note that the telegraph line has already been established. Work proceeded simultaneously along many points on the line, and good communication was essential.

Text by William H. Bunting from A Days Work, Part 2, A Sampler of Historic Maine Photographs, 1860 - 1920, Part II. Published by Tilbury House Publishers, Gardiner, Maine. 800-582-1899