BACK THEN

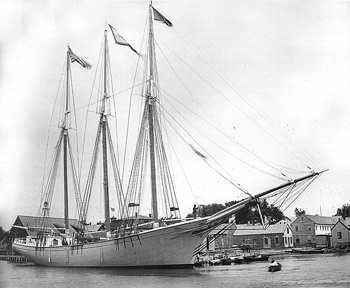

Schooner Golden Ball

Photo courtesy of of The Brick Store Museum, Kennebunk, ME

Kennebunkport, 1890. The schooner Golden Ball, newly launched from the yard of David Clark, floats in the Kennebunk River. About 2,250 three-masted schooners were built on the East Coast, the vast majority from the end of the Civil War to World War I; about a thousand of these were built in Maine. Twenty-eight were built on the Kennebunk. Of the eleven built by David Clark, several were particularly notable. The George V. Jordan, built in 1874, twice made two-year world voyages, once sailing from New York to Sydney in but ninety-six days. The long-jibboomed Lavinia Campbell was among the handsomest members of the coal fleet. The Bradford C. French, at 900 tons, was the largest member of the breed.

Clark also built three of the smallest three-masters, the dainty Joseph G. Dean, Pardon G. Thompson, and Julia Frances. These shoal and handy little flyers, all built to a model cut by Captain Zabina Chase of New Bedford, for New Bedford and Fall Fiver owners,were intended for the southern fruit and oyster trades and for delivering supplies to the Azores for the whaling fleet. Among the fastest schooners on the coast, their appearance at Bangor, when later employed coasting, was a newsworthy event. The Dean, “built like a pirate,” made a round trip between New York and Baracoa, Cuba, in twenty-two days, and between New Bedford and New York in four, including time spent working cargo. The 286-ton Golden Ball, more than one hundred tons larger, otherwise resembled the fleet-footed trio and was also built for a New Bedford owner. She was arguably the last word in three-masted clipper schooners. From 1800 to 1918, well over 800 vessels were built in the Kennebunk region, nearly 170 of them full-rigged ships. The vast majority slid into the river, which was always ice-free. Many of the ships were built for the cotton trade, many for local owners and many for Boston owners. Kennebunk area-built ships were said to load more cotton for their tonnage than any but Boston-built ships. The largest vessel launched into the little river was the 2,516-ton, four-masted bark Ocean King, built in 1874.

Early shipbuilders used local timber and established yards as far up river as possible, aiming the launching ways up the narrow stream. As bigger ships were built, there was insufficient water to float them out, and in 1848 a set of locks was installed to capture the flood tide. The largest of the twenty-nine vessels to transit the lock was the ship Golden Eagle, of 1,273 tons, which barely scraped through. After 1867, all shipbuilding occurred downstream, at Kennebunkport. (By this date most timber had long since been arriving from the South by schooner.)

In 1880, the Kennebunk area’s shipbuilding-related employers included six “shipbuilders and contractors,” eight master carpenters, six shipsmiths, six ship joiners, two caulkers, three fasteners, one rigger, two sailmakers, two pump and block makers, one sparmaker, one boatbuilder, one cooper and tank builder, one brass and composition founder, one iron founder, and one caboose (portable galley) and tinware maker.

Over a fifty-year career, David Clark built one hundred vessels – ships, barks, sloops, steamers, and schooners — and enjoyed the highest reputation. (He was seriously injured by a timber while building the Golden Ball.) Another builder in the final years, Norwegian George Christenson, built several of the most noted clippers in Portland’s crack mackerel fleet. He also built two three-masters, is known to have modeled a lofty three-master built at Richmond, and may well have designed coasters built at Kennebunkport as well.

The slight hog, or arc, to the Golden Ball’s jibboom – the long spar atop her bowsprit – may have added some spring to the rig while definitely adding to her seductive good looks. The inboard end tapers gracefully into the buffalo rail. Each mast has a slightly different rake, or angle, fanning the top-masts apart to prevent the optical illusion that they are leaning inward. The temptation to add additional rake has wisely been resisted, since rake impaired the set of the sails. The foremast was subjected to the greatest strain and is provided with additional shrouds. In her every aspect, the Golden Ball displays a masterful interplay of artistry and practicality.

Text by William H. Bunting from A Day’s Work, A Sampler of Historic Maine Photographs, 1860-1920, Part I. Published by Tilbury House Publishers, Gardiner, Maine, 800-582-1899