Castine. The view from Dice's Head, to the north, toward Fort Point, commanding the entrance to the Bagaduce River. Tom Seymour Photo Castine. The view from Dice's Head, to the north, toward Fort Point, commanding the entrance to the Bagaduce River. Tom Seymour Photo

|

George J. Varney, of the Maine Historical Society, in his A Brief History of Maine, 1890, mentions that in 1625, King Charles of England ceded “New Scotland” to France. This encompassed lands east of the Penobscot River including present-day Castine. This area was earlier given to a Scot, Sir William Alexander, who was to settle Scottish people here. Alexander’s efforts were essentially without success though, because potential settlers feared that the land would soon fall to the French.

In view of impending failure, Alexander sold New Scotland to M. La Tour, a French Huguenot. La Tour had hopes of establishing a French colony in the region. However, Alexander included in the conditions of the sale a codicil dictating that La Tour was to hold the land subject to the Scottish king.

However, La Tour clandestinely enticed from the King of France a patent to the territory. Now, La Tour was to hold the land as a French subject. Contention swiftly built as the English Parliament ruled against King Charles, claiming that he had no legal right to cede the territory without express permission of Parliament. In the meantime, France, acting quickly and with firm resolve, took possession of this disputed land east of the Penobscot River and named it Acadie (the Acadia of today). Because of this claim, however tenuous, France felt justified in plundering English houses and ships.

In 1630, according to George F. Wilson in his classic book, Saints and Strangers, Isaac Allerton reported to the Plymouth Colony that the Undertakers (a group of supporting businessmen/ investors) of London had procured a “tract of land along the Penobscot River about fifty miles up the Maine coast from the Pilgrim trading post on the Kennebec.” This was, as the text later explains, at Pentageot, later Castine.

Wheeler’s book says of this post, “This trading house, like all others of that period, was built for defense, and was probably surrounded by a stockade.” Wheeler goes on to describe how in 1635, Charles de Menou d’Aulney attacked the trading post, driving away the inhabitants. The Plymouth Company later mounted an unsuccessful effort to regain possession.

In 1667, the Frenchman Baron Jean-Vincent de St. Castin assumed command of Pentagoet. Castin, or as later referred to by English-speakers, Castine, married the daughter of the sachem of the tribe of Penobscot Indians. According to Varney, Castine became himself a sachem of the tribe and thus, if Varney’s account is correct, Castine held rule over the indigenous people as well as the colonial French settlers.

Dutch Involvement

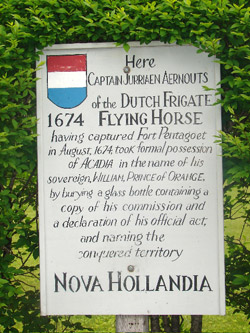

But Castine’s grip on the peninsula, like that of the earlier English, was to be loosed by force. In 1674, Holland, a nation who had long envied the French for their holdings at the mouth of the Penobscot River, attacked and captured Fort Pentagoet. In August of that year, Captain Jurriaen Aernouts (or Aernoutsz) of the Dutch Frigate, Flying Horse, captured Fort Pentageot and claimed possession of Acadia in the name of William, Prince of Orange.

Aernouts thought to make his deed official by burying at the site a glass bottle containing a copy of his commission and a declaration of his taking formal possession. Aernouts re-named the region Nova Hollandia, or New Holland. Then Aernouts sailed off in search of further plunder.

In 1676, the Dutch returned and this time, after bombarding the fort, seized it and used the fort’s own guns to completely demolish it. But again, Dutch presence was short-lived, and in that same year, Castine returned in person, to retake the place for France, naming it Bagaduce. After establishing adequate fortifications on what little remained of the fort, Castine built a trading post and he and his family enjoyed some years of relative tranquility.

The Treaty of Nijmegen resolved war between France and Holland in 1678. At that time, the Dutch renounced their claim to the land.

In 1667, the Frenchman Baron Jean-Vincent de St. Castin assumed command of Pentagoet. He married the daughter of the sachem of the tribe of Penobscot Indians, became himself a sachem of the tribe and thus, held rule over the indigenous people as well as the colonial French settlers. Tom Seymour Photo In 1667, the Frenchman Baron Jean-Vincent de St. Castin assumed command of Pentagoet. He married the daughter of the sachem of the tribe of Penobscot Indians, became himself a sachem of the tribe and thus, held rule over the indigenous people as well as the colonial French settlers. Tom Seymour Photo

|

English Return

In 1692, England seized Castine/Bagaduce and again destroyed the fort. After this, the area saw little in the way of settlement and only in the 1760s, with the end of the French and Indian War when England gained rule over all of North America, did lands on the peninsula see an influx of settlers.

For so long, the Bagaduce, so-called, had only temporary settlements. The vicissitudes of war, politics and craving for personal power saw to that. But now, with clear title to not only lands in eastern Maine but also most of North America securely and without challenge in the hands of the English, permanent settlements slowly but surely sprang up in formerly wild, unsettled regions.

Life was unduly difficult for these early American colonists. A narrative in Wilson Museum Bulletin Volume 1, Number 10 for summer, 1967, paints a stark, cold picture of conditions faced by those who would start a new life and raise their families here.

Charles and Mary Hutchins left York, Maine and sailed to the Bagaduce. There, they settled. The account goes on to say, “They were often so scantily supplied with food that to lengthen out their little store of Indian meal the children would go to the woods and gather herbs which they would steep and mix with their meal to a porridge.”

Continuing, the story reads, “To say that he (Charles Hutchins) was poor would convey a very inadequate idea of his condition, when he laid the cellar wall for his house he carried stones in his arms for that purpose from under the shore, a distance of forty rods or more. To get money with which to buy glass and nails he cut and carried to the shore on his shoulders a freight of wood, some forty cords, which he sold for forty-two cents per cord.”

The settlers persevered and in time, managed to establish log homes, clear land and build sawmills. Since roads were as of yet few or non-existing, travel and trade was principally conducted by boat, one of which each family owned, out of necessity. Fishing, too, became a way of life and boats and boat building became integral parts of everyday life in those early days on the Bagaduce.

Storm clouds Gather

As settlements grew up and down the Maine coast, so did tensions between American colonists and Great Britain. In addition to earlier settlers, Tories, people sympathetic to the British Crown, took up residence on the Castine peninsula, thinking it a safe place to live should events eventually lead to open warfare.

And of course, war came. The next installment of this piece will center upon the events of the Revolutionary War as well as those of the War of 1812.

|