Simply built of heavy timber the gundalow drew very little water, could slip onto a muddy shore, be poled over shallow water, and raise a sail to move a heavy load. The simple construction encouraged the owner builder with no doubt mixed results. Gundalow Co. photo |

The conditions in the shallow tidal basin area around Portsmouth, New Hampshire were a special case. Several towns in the area, including Durham, Newington, Newmarket, Exeter, South Eliot and South Berwick, developed along the Piscatqua River, and on its network of tributaries and the shallow Great Bay, which is seven miles upstream. The area for several miles up the Piscataqua and east to Saco had been prime mast pine forest. The low flat terrain was dense with these giant first growth white pine. Cutting mast pine contributed to the early development of many towns in the tidal basin.

By 1750 Portsmouth had become the primary shipping point for mast pine to the British Navy in the years before the American Revolution. Mast pine for the British Navy, shipbuilding, and shipping were the early industries that built the town of Portsmouth. From the colonial mast pine industry to the building of John Paul Jones’ first ship the Ranger, to the Naval shipyard at Kittery, and the sinking and great rescue of the submarine Squalus off Portsmouth, the town has been a center maritime industry.

The upstream towns were engaged in agriculture and manufacturing. Domestic and foreign imports arrived at Portsmouth on ships too large to navigate the Piscataqua River. Portsmouth was their access to markets. The condition of roads at the time made them a last resort choice for transporting cargo, and not a choice at all in mud and snow seasons. Manufacturers and seasonal crop farmers needed more reliable transportation.

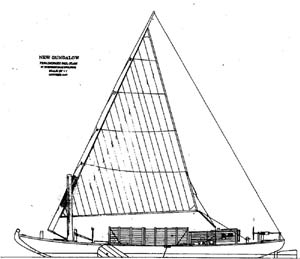

The solution was a simple shallow draft vessel that could reach these growing river ports. A barge in its earliest configuration, the gundalow was poled over the shallows, rode the tide in and out of the Piscataqua, was rowed with long oars called sweeps, and later carried a large sail. With as many spellings as explanations for the origin of the name, a common belief is that the name came from the gondolas used in Venice, Italy.

The gundalows were simply built, many were little more than rafts. Some were 70 feet long and built to protect the cargo. Farmers often built them using whatever lumber was available to transport their own produce, and launched them where their fields met the river. They were built to very general specifications with variations freely added. Some farmers got into the business of transporting goods. By the mid-1800’s gundalows were commonly seen around the tidal basin. Short-lived, abandoned barges along shore were a part of the landscape. These shallow drafted types of cargo ships reached their highest state of evolution in the Great Bay of New Hampshire and Maine in the late 1800’s.

Though virtually everywhere along the waterfront in their day, they have not been given much attention over the years. They had none of the design attractions of the sloop boat, coastal schooner or the clipper ship. It was not a performance vessel. It was slow, plain, designed for utility. But the gundalow played an important role in the transport of many of the things people used every day, and was something very visible along shore.

The unique topography of the low land around Portsmouth made a vessel like the gundalow essential for the towns developing around it. Shallow bays, rivers and streams were the highways. Gundalow Co. photo |

Cotton bales shipped from southern states to Portsmouth, were taken on gundalows to cotton mills in South Berwick, Durham and other towns. They also brought out the finished cotton products. The tidal basin area produced large quantities of marsh hay, which along with farm produce, cattle, lumber, firewood, and passengers were among the regularly shipped items. Anything that would be shipped by local trucks today went by gundalow then.

Most of these vessels operated close to home, but a few with sail rigs would go as far as the Merrimack River or the Saco and Neddick Rivers. They were not sea vessels. The sails where rigged on a short stout mast, about 12 feet above deck. The lateen sail was rigged much like the Dhows of the Red Sea and Middle East. The long boom, in some cases 70’, could easily be lowered for passing under bridges. The boom was hung on a chain from the top of the mast, about a quarter of its length from the boom’s forward end. Balanced there, the forward end was secured to the deck with block and tackle near the bow. The aft end of the boom, pivoted on the top of the mast was raised above deck at about 45 degrees.

The Fanny M., launched from Adam’s Point in Durham, NH in 1886 by Captain Edward H. Adams, was the last gundalow to operate commercially in the area.

The 20th century brought the demise of the gundalow, but Captain Edward Adams (1860–1950) bridged the gap between the gundalow epoch and today. He stirred the minds of many of the visitors at his Adams Point home by arguing in vain for a high sailing vessel clearance on the proposed Dover Point Bridge (1933), and then, with his son Cass, building a “pleasure gundalow” (1950). Evoking the spirit of an age he felt people were ignoring, his determination and ‘sense of place’ live on through the gundalow that bears his name.

Unlike earlier times, the building of this gundalow was to take its builders far beyond the region to locate the large and specially formed framework to complete the vessel. From the main member kilson logs (Fremont, NH) to the hackmatack knees (Cherryfield, ME), the construction of the Captain Edward H. Adams became a prime and unusual attraction at its Strawbery Banke (Portsmouth, NH) site. The stump mast from Durham, NH and the 69-foot spar from a windjammer in Rockland, Maine [now a 70-foot purpose-felled Maine White Spruce] completed the search for parts. In keeping with tradition, most of this gundalow is held together with 5,000 trunnels (tree nails or pegs).

The Gundalow Company operates the world’s only remaining gundalow, Captain Edward H. Adams, which was built at Strawbery Banke Museum in 1982. The replica gundalow visits riverfront towns in the Piscataqua Region, providing a stationary platform for “dockside” maritime heritage and environmental education programs.

A new gundalow will be built in 2009 that will be Coast Guard approved for carrying passengers. Wooden shipbuilder Harold Burnham of Essex, Massachusetts will be building the gundalow at Strawberry Banke in Portsmouth. Burnham has built several large wooden vessels which include the 65' Gloucester fishing schooner the Thomas Lannon, a 40' Maine Pinky, a colonial era 35' Chebacco boat, and others.

|