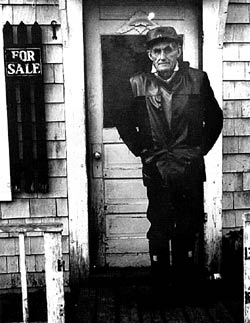

Stacy Prior 78, around 1960 in front of his home in Medomak, Maine. Prior fished about 60 traps from a rowed dory in the Medomak River. The federal prosecutors tried to translate a scuffle with relatives into evidence of Stacy’s trade being restrained by the MLA under the Sherman Antitrust Act. Photo courtesy of Everett Boutilier. |

At the time there were about 125 dealers in Maine. It was well known that the few lobster dealers controlling the market communicated with each other. Among themselves they decided what the price for lobster would be on any given day. The problem for the fishermen was that the price was often below a living wage. Compounding the problem was the enormous power some dealers had over many fishermen. Some had borrowed money from dealers, others knew the dealer could at any time refuse to buy their catch.

The power of dealers like John Willard of Willard-Daggett in Portland was unchallenged and unquestionably the law on the Portland wharfs in the 1950s. His influence extended down the coast to Penobscot Bay. Willard had taken over his father’s established business, becoming vice president in 1952 at the age of 43. He enjoyed the rough and tumble dealings of the market. Cutthroat and feared for it, he was known to say that making a competitor or uncooperative fisherman lose money was better than making money.

The dealers were getting rich and the fishermen were going broke; pretty simple. By the summer of 1956 the fishermen knew they had to do something if they were to continue fishing. They could not afford to fish for 30 cents a pound with rumors of 25 cents in the wings, but 35 cents seemed like an acceptable minimum. Talk began to spread of these numbers along with staying in or tying-up if the price paid wouldn’t cover costs. The Maine Lobstermen’s Association and its president, Leslie Dyer responded to the low price by calling for a tie-up and not fishing. After World War II boats had radios; these and telephones made the rapid spread of this plan possible. The week long tie-up resulted in the price stabilizing at $.35.

The following summer low prices were again challenged. At the time there was a lot of lobster and the price of bait and gear etc., was going up. This was by no means unique to 1957. The question then, at a time when 5 cents made a difference, was why the 5-cent drop in price was not from 55 to 50 cents. The price of lobster had long been out of the hands of the lobstermen. What made the late fifties different from earlier times was a growing affluence in the country, new communications systems, the higher economic expectations of lobstermen, many of whom had served in World War II and the effect of all these on the visible income disparity between catcher and dealer.

The Maine Lobstermen’s Association had about 1,500 dues-paying members in 1957. There were about 6,000 fishermen in Maine then. On July 16, 1957 Portland dealers cut the price on soft shell lobsters to 30 cents. In response, over a hundred fishermen held a meeting on the roof of the Harris Company ship chandlery building at the wharves in Portland on July 17. At the meeting were mostly Casco Bay area fishermen. Leslie Dyer then 48, a Vinalhaven lobster fisherman, well respected for his intelligence, wit and easy going self-confidence rushed to the meeting. Talk of whether to fish or not spread down the coast. Some who could not well afford to tie-up, said they tied-up out of a feeling of comradery with their neighbors and fellow fishermen. The tie-up lasted a week with some estimating that 4,000 fishermen participated. A second tie-up was planned for the first part of August. Aware of the laws regarding strikes Dyer drove home the phrase, “It’s a tie-up, not a strike.”

On August 5, Willard met with other dealers in Rockland to discuss the situation, hoping the fishermen’s disunity would end the tie-ups. John Willard would then do the logical thing for a dealer who knew he was getting rich on the efforts of fishermen barely surviving. He had the federal government charge the fishermen with conspiring to fix prices under the Sherman Antitrust Act.

Willard had his brother Phillip, a Portland lawyer and business associate, contact the local federal district attorney Peter Mills. Phil walked over to Mills’ office and brought to his attention the section of the Sherman Antitrust Act pertaining to conspiracies and the restraint of trade. He said the tie-up and the role of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association were subject to this section. Willard pressed Mills to call the Justice Department in Washington to initiate an investigation. To put the case and the times in perspective, the prosecutor while not objecting to the appropriateness of the call, baulked at paying for the long distance toll. Phil Willard, sensed this, charged the call to his phone and made the call for Mills.

Washington sent a “team” of antitrust lawyers looking to make reputations for themselves to Portland. The response was unusually rapid. Justice Department officials arrived on August 9, the day the August tie-up ended.

The Sherman Antitrust Act was passed by congress in 1890 to regulate giant national corporations like Carnegie Steel, Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, Sucony Vacuum Oil, etc. These monopolies dominated markets and had many millions of dollars in corporations with enormous influence on the economy, and the power to change the course of history. In 1957, the Sherman Antitrust Act was brought to bear on an attempted 5 cent change in the price of lobster.

The trial started May 19, 1958 at the federal courthouse in Portland, with Leslie Dyer the focus of the government’s case. His lawyer, a Boston transplant very well regarded in his Rockland community, was Alan Grossman. Grossman had defended fishermen working with Les Dyer and the MLA on fishermen’s interests in the past.

The government’s team of lawyers called in a long list of witnesses. Their goal was to prove that Dyer had talked with other fishermen about not fishing as a means of raising the price of lobster. This, they said, would constitute conspiracy and restraint of trade. They also made a great effort to find someone who would testify that the MLA was intimidating fishermen to stay in. They failed to do this.

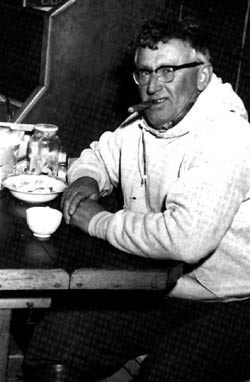

Lester Teele, 1962, in the forecastle of the sardine carrier Beverly Ann. Lester, Stacy Prior’s nephew, was described by federal prosecutors as having pulled the painter on his uncle’s row boat while it was being used to haul traps. Lester was therefore considered to be restraining trade as a member of the MLA in 1957. Photo courtesy of Everett Boutilier. |

Witnesses for the defense were grilled on the stand from several angles to get them to say the magic “strike” or “minimum price” words that would lead to a conviction. Unfamiliar with fishing, fishing terms, Maine or Maine jargon, the government lawyers were a laughing stock to most people in the courtroom, including, at times, the judge. The government lawyers carefully laid out their word traps for the fishermen. But the fishermen “didn’t remember who was at the meeting,” or “just what was said,” or recall discussions on the 5th of whenever. Myles “Mike” O’Reilly, a fisherman from Cliff Island, was a witness whose testimony offers an example of what the feds were up against.

When Nowlin, the government lawyer, asked O’Reilly how long he had been a member of the MLA he responded, “Since the beginning of it.” “When did it begin?” “I don’t know.” “Is it 10 years old, 20 years old, 2 years old?” “I wouldn’t say it was 20, no.” “You have been a member since its inception, you said?” “That’s right.” “Is it three years old?” “Could be.” Nowlin fumed and said sharply: “Mr. O’Reilly, I really wish you would answer, if you know, about how many years the organization has been in existence; if you don’t know, of course, you can’t answer, but if you do recall, how long have you been a member of the association?” All innocence, O’Reilly patiently replied, “I told you, I didn’t know.” “Is it less than 10 years?” “I don’t know.” Nowlin changed the subject. After his testimony O’Reilly would slyly tell Nowlin during a recess in the corridor, “If you’d asked me the right questions, I’d a-told you more.” (From The Great Lobster War, by Ron Formisano, UMass Press, 1997.)

Asked what occurred on a particular day at particular place, and the government lawyers would hear about Aunt Minnie’s trip to Augusta. Fishing terms, local jargon, regional references and insider comedy had the government “team” chewing the cuffs off their expensive suit coats in frustration.

It was not those lawyers who won the government’s case, but the instructions to the jury by Judge Gignoux. After closing arguments, the judge explained the law’s meaning of the term conspiracy as “a combination or agreement among two or more persons to accomplish an unlawful purpose or act.” His final instructions to the jury were that they needed to decide “whether the tie-up of the lobster fishermen along the Maine Coast last summer was the result of a mutual agreement or understanding…to refrain from hauling their traps until a better price for their lobsters could be obtained; or whether that tie-up represented individual actions by the fishermen resulting from decisions independently arrived at by each individual concerned.” After four hours of deliberation the jury returned finding the Maine Lobstermen’s Association and Les Dyer guilty. Dyer was fined $1,000.

The dealers meeting in Rockland to strategize led to them being charged with price fixing also. However, the result for the dealers was a fine of $500 for some and a $1,200 fine for John Willard. Rumors had circulated that Willard was fined $10,000. Though this was false, $10,000 would still have been a bargain for control of the price of lobster. For $1,200 and no other expense to him, Willard, through the court, prevented the lobstermen from ever challenging him in the only way that had ever been effective. Leslie Dyer, Jr. recently said his father’s response to the court’s decision was relief that it was over, for it had gotten so out of hand with all the publicity the case generated.

One outcome of the publicity about the tie-ups and trial was the spread of co-ops along the coast. The knowledge was not lost on the fishermen that they could organize to affect change. They did not win in court, but a large number of fishermen were brought together in a common cause.

This story was originally published here March 2002.

|